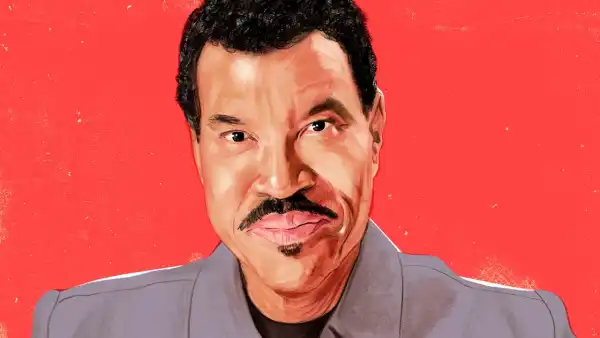

The actor Rami Malek was sitting on the patio of the Whitney Museum café when a boy clad in a monochrome black outfit nervously walked toward him. “Can I just take one photo? I came all the way from Portugal.” Malek turned, laughing, creases forming around his ice-blue eyes. “You came all the way from Portugal to say hi to me?” The boy was unphased by the jest. He put one arm around Malek and snapped a selfie. He said, “I’m very sorry”—his voice trailed off—“to interrupt.” Malek, who was clean-shaven and wearing a black shirt jacket rolled up at the cuffs, has grown accustomed to being recognized since playing the hacker Elliot Alderson on the cult-hit television show “Mr. Robot.” He had just returned from Europe, where he’d been on tour to promote his most recent film, “Bohemian Rhapsody,” in which he plays a wildly different role: the lead singer of Queen, Freddie Mercury. “It is quite nice playing Elliot in this city. It is one of the coolest experiences an actor can ask for,” he said, looking out to the street. “And then comes this,” he added, of the Mercury role. “It flips your entire interpretation of what you do for a living on its head, and what you enjoy. I thought this kind of reclusive introspective human would be the be-all-end-all in terms of character work, and then to be prancing on the stage in a sequin leotard a year later became my new normal.”

Going on a big promotional tour, like wearing sequins, was a new experience for him. “I took my mother. She appreciated it,” he said matter-of-factly. It’s not unusual for Malek to take family to industry events. Two years ago, he took his cousin to the Emmys. “I have cousins, yeah. I always refer to them as my immediate family, and my brother the other day was, like, ‘They’re not your immediate family, you just grew up thinking that,’ ” he said, pushing open the glass door to an exhibition of the work of the artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz. Malek was born to Egyptian parents who had moved to Los Angeles. When he was growing up, his father regularly woke him and his siblings in the middle of the night to speak to cousins in Egypt. “As far as my father was concerned, we were going to know these people,” he said.

Like Malek, Mercury was from an immigrant family. He was born Farrokh Bulsara, to parents of Parsi descent, in Zanzibar, an archipelago off the coast of Tanzania. He moved with his parents to England when he was a teen-ager. “When you begin to make these discoveries about him, his heritage, his name, Farrokh. Farrokh Bulsara. I mean, it could be an Arabic name, no? If your friend sitting next to you in school’s name is Farrokh? So I’m, like, O.K., I might know this guy,” Malek said. “I may have met him somewhere in my youth.” Growing up in the eighties and nineties in Los Angeles, Malek felt that his name, Rami, “stuck out like a sore thumb,” he said. “I felt that we stuck out like a sore thumb, as a family, our traditions. Going to school with that type of consciousness, and feeling like we were wearing our heritage on our sleeves, was always something that was confusing. I was conflicted about how to identify myself as a young man, and I think that is very much emblematic of Freddie Mercury.” He added, “I like characters who have a moral predicament with themselves that they refuse to . . . what’s the word?” “Confront?” I offered. “ ‘Confront’ is the word.” He lit up. “Sorry, Arabic is my first language, as well,” he said, in jest, referring to our shared Egyptian background. Malek spoke Arabic at home until the age of four, though his Arabic has long since been superseded by his English.

After watching “Bohemian Rhapsody,” it’s hard to unsee Malek as Mercury. But, despite a resemblance to the singer that may seem obvious in retrospect, securing the role wasn’t straightforward. While Malek was in New York shooting “Mr. Robot,” two of the film’s producers, Denis O’Sullivan and Graham King, called and asked him if he could put himself on tape. He’d already interviewed and was assured that he had the role, but the producers still needed to persuade others. “You know what it’s like in our business,” he said flatly. Malek was unsure about how quickly he could get into a Mercury frame of mind. “I did an audition in which I picked one of his interviews online and incorporated the questions into my answers, because I didn’t have anyone to read with. I put it on tape in the living room. I was watching and watching, and I got captivated. I said, ‘Oh this is going to be very different.’ But immediately I heard my voice doing different things, and my hand moving in a different way.” The film hadn’t been funded yet, but each night Malek would go home and watch archival footage of Mercury. He persuaded the producers to send him to London, where he got a dialect coach, a movement coach, and took singing and piano lessons. For four hours a day, he watched videos of Mercury with his movement coach. “We would just sit there and watch him in an interview, and see when he moves in and out, and blinks, and covers his teeth. Why is he covering his teeth? And then, maybe two hours later, we’d be running through ‘Radio Ga Ga’ in Live Aid sequence, or doing ‘Killer Queen’ in the style of Marie Antoinette.”

Malek was not without trepidation when embodying Mercury. “The honor and horror of playing the man,” as he put it. But, the more he prepared for the role, the more excited he became about shooting the reënactments of famous Queen performances. “When I started to embrace that aspect of him—the mischief, the joy, the freedom, and the lack of any inhibition, or so it seems—that’s when the real spontaneity started to occur for me. Basically, the ownership of it. And that was him—tremendous ownership of who he was.”

It hasn’t always been easy for Malek to secure leading roles. He played a pharaoh in all three of Ben Stiller’s “Night at the Museum” comedies and had a recurring role as a terrorist in the TV drama “24,” and he grew sick of the typecasting. When he won the Emmy for Best Actor in a Drama, in 2016, for his performance in “Mr. Robot,” he was the first nonwhite actor in eighteen years to do so, and his success was regarded as a victory for minority actors everywhere. “People didn’t know where to place me with my ethnicity, and never was I ever up for leading anything,” he said. “The fact that Rami Malek got to play the lead character, called Elliot Alderson, in ‘Mr. Robot’ was somewhat of a coup, I think. I never saw that possibility when I was younger.” He speculated that ten years ago a white actor would almost certainly have been cast to play Mercury. “We might not be going down the Farrokh Bulsara road of this story.”

On his way out of the gallery, Malek’s attention was caught by a blue-tinted collage with a stencil drawing of two men kissing in the center, titled “Fuck You Faggot Fucker.” “Something oddly uplifting about it,” he said, a little puzzled. “I suppose it’s the color. Phenomenal when you color grade a film, the color can just change emotions immediately. The scene where Freddie gets diagnosed, you’d be very surprised how changing the color could affect your emotions. I mean, that painting there had nice cloudy blues. Sky blues, not moody blues, and, all of a sudden, it was an uplifting painting.” He briskly walked down the stairs. “Let’s go outside and talk about uplifting things.” Outside the museum, away from the crowds, walking along a quiet stretch by the Hudson River, Malek returned to the sequin leotard that he wore in the movie. “I’d seen photos of this kind of glam rock, but to think that I’d be in that sequin leotard . . .” he pondered aloud. “For a second, I was, like, this is going to take some getting used to, but by the end of it I was holding the sequin-leotard thing, saying, ‘Can you make me this in ruby-red?’ ” Malek also had to get used to singing in a set of false teeth, which he wore to mimic the singer’s overbite. “I kept the teeth,” he said. “Well, I had the teeth cast in gold. It is the most ostentatious thing I have probably ever done, and, in the spirit of Freddie, being as outlandish as I could, I said, ‘What would be more him than casting these in gold?’ ”

Sourse: newyorker.com