All over the world, some 10 million people have had their DNA analyzed by a direct-to-consumer genetics company like 23andMe, Ancestry.com, or MyHeritage.

From a cheek swab, these companies scan millions of spots on a person’s genome and generate information on where your ancestors came from, and even identify long-lost relatives.

This is the powerful idea behind ancestry testing: You can find your people. But it also means you can be found.

So many people have now used the services that many of us don’t even need to share our own DNA to be tracked down. Your father — or perhaps a third cousin whom you’ve never even met — could have uploaded their data, which could lead to you. This is how police cracked the cold case of the “Golden State Killer” earlier this year: An old DNA sample from a crime scene matched with the DNA of the killer’s relatives in public databases, which, after some more sleuthing, led to him.

Now, a report in Science quantifies just how many Americans of European descent may be found in this manner. In the paper, the researchers ask: If you were to take any given person, what is the probability you can find some of their relatives in the database?

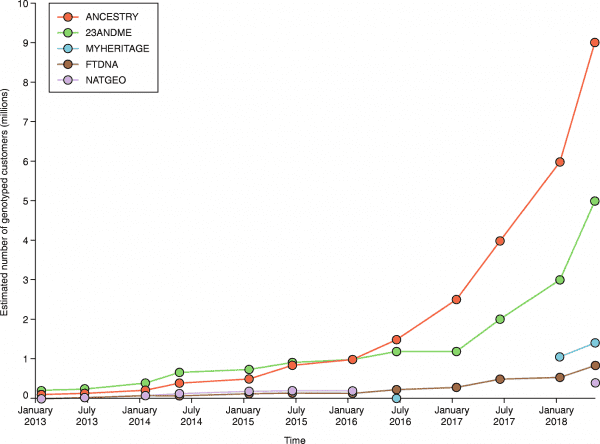

The study concludes that around 60 percent of Americans of European descent could be matched to a third cousin or closer relation. And this percentage is only set to grow in the coming years, as more people give their genetic information over to these companies. The chart below shows that the number of people who have had their genomes analyzed by direct-to-consumer companies has increased greatly in recent years.

It’s a breakthrough for law enforcement to be able to use these public databases to track down killers in cold cases. But with it, we are entering a brave new world of shrinking DNA privacy, with potentially harmful consequences. Consider a scenario where a hostile government starts tracking down protestors via spit from a rally.

But before we panic about our identities being exposed, it’s worthwhile to walk through the way all of this works. It’s not the case that a third-cousin match would immediately lead to your identification. It’s a lot harder than that.

“The 60 percent figure doesn’t mean we can identify each one of these individuals,” says Yaniv Erlich, the lead author of the paper, who is also the chief science officer at MyHeritage, one of the top DNA-ancestry companies. It means “we can find a relative for these individuals. It still requires some work to get a person.”

How law enforcement can track a person down via their relatives in genealogical databases

If you want to learn more about your ancestry or risk of certain diseases with a DNA test, you can have 23andMe or MyHeritage do the testing. In these tests, they take a swab of cells from your cheek and analyze spots on the genome where people tend to differ from one another. (Since all humans have remarkably similar DNA, it doesn’t make sense to read every single letter.)

These small differences can help explain why some people have blue eyes, and others brown. These differences — many which are biologically meaningless — are also passed down the generations. That’s why they are useful in tracking our ancestry and finding relatives.

You can also upload a DNA file you’ve obtained from another service on a third-party site.

But it’s not the case that when a third cousin of yours uploads their DNA to a genealogical website, your identity is immediately made public on these websites. Not at all.

For a law enforcement agency to find you, they’re going to need some of your genetic material to test first. Then they could try to find any relatives in the database, and then figure out their relatives, which could lead them to you.

That’s what investigators had in the case of the Golden State Killer (and in the cases solved since with a similar method).

But there’s a big caveat here:

Ancestry DNA companies’ clientele is mostly white Americans of European descent. If you’re not related to white Americans of European descent, investigators probably can’t find you. (This point also reveals another fact: If you’re not white, genetic companies may be less useful for you in tracking down relatives.)

Okay, let’s say you’re a white American of European descent whose DNA has somehow fallen into investigator’s hands. Are you exposed?

Erlich explains that, on average, a person has around 850 relatives who are third cousins or closer relations. (Consider what a third cousin is: These are relatives you share a great-grandparent in common with. It can be a lot of people!).

So if one of your third cousins is revealed while searching your DNA, investigators still have a lot more work to do: That’s around 850 people to comb through before finding you. And even then, they would need more clues.

Let’s say investigators can guess your age. “Just this information will reduce your search space by a factor of 90 percent,” Erlich says.

And let’s then say investigators have a hunch about where you may live. They pick an area on the map with a 100-mile wide diameter. “This will exclude another 50 percent of your searches,” he says.

You can cut the number of hits in half again just by excluding males or females.

“Altogether, we go from 850 individuals on average to something on the order of 16, 17 individuals,” Erlich says. “At that point, you can use more elaborate tactics to really get to the person.”

It’s getting harder to hide

On the same day Erlich published his paper in Science, another paper on DNA privacy was published in the journal Cell. The topic of this paper was narrower, but it shows another unexpected way DNA privacy may be breached.

When law enforcement collects DNA from a suspect, they typically analyze it with a technique called STR (Short Tandem Repeat). This technique is supposed to strip the DNA of biologically relevant information (things like eye color, skin color, or disease) and just be a means to identify people. In that way, it’s like a fingerprint.

The information is stored in a database called the Combined DNA Index System (or CODIS) that law enforcement can access. What the Cell paper revealed is that information in the CODIS database can sometimes be matched with relatives in ancestry databases. The Cell study found that in a sample of 872 people, 30 percent could be matched via cross-referencing STR data with the ancestry data.

The whole reason the government uses STR, according to Jaehee Kim, a Stanford biologist who co-authored the study, is that it doesn’t reveal biological information. That’s for privacy reasons: It’s routine for police officers to take DNA swabs from people arrested for violent crimes. In fact, in 2013, the Supreme Court decided that these swabs — taken without consent — didn’t violate the “unreasonable search and seizure” clause of the Fourth Amendment because the STR information does “not reveal an arrestee’s genetic traits.” Analyzing a person’s DNA is potentially more revealing than rifling through their home — but police need a warrant to enter a home.

Yet the new study in Cell shows STR data can possibly reveal genetic traits, if matched up with an ancestry archive.

The bigger point here is this: There are more and more ways that data uploaded to ancestry databases can be used in criminal investigations. When you upload your own DNA data, you’re potentially giving a clue to law enforcement to find a family member. Perhaps that’s something you didn’t intend to do when wondering if you’re more Greek or Austrian.

The more people who upload their data to ancestry sites, the more we all may be findable. Erlich suggests we need some safeguards. Some sites, like GEDmatch, allow users to upload DNA data obtained from other companies. That raw data, Erlich suggests, should come with a key that explains where it originated, and perhaps even who owns it. That way, a company like GEDmatch could be sure the person uploading the data is uploading their own, and not snooping around to identify someone via their relatives.

That “someone” snooping around may not even be law enforcement. It could be a foreign government — or someone engaging in a very 21st-century version of stalking.

It’s against the terms of service of these sites to upload data that’s not your own, or without a person’s consent. But more safeguards need to be put in place.

Sourse: vox.com