Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

She’s offered us everything save for her visage. Which signifies she’s presented us with both totality and nothingness. “Masked Nude, Harlem NY,” a monochrome image from 1999, stands as a work as contradictory as its given title. A Black woman rests upon a divan. Her loose extremities hang all across the plush material, her groin area scarcely veiled. She is posed akin to the subjects favored by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Gustave Courbet. Yet, this woman would never have been considered their inspiration. She finds herself captured by Coreen Simpson, a twentieth-century Black female artist, with twentieth-century concerns at heart. Simpson—a lenswoman, a gems designer, and a scribe—is, at her essence, a documentarian of style. For decades, she has explored both uptown and downtown locales, endeavoring to grasp the public’s essence by immortalizing how they aspire to appear. Or to not appear: by gifting us bodies instead of countenances, Simpson takes part in a variety of anti-portrayal. She refashions, within her masked-nude photographic works, the Black female as an emblem of concealment.

“Masked Nude, Harlem,” 1999.

“The face held little importance in the story of nude photography,” Simpson stated, in a conversation not too long prior. And the mechanism Simpson implemented to cloak the visages of the figures within her works? That mask we categorize as “African,” an epithet nearly emptied of its implications. One of the notions Simpson seems to examine through her masked-nude series, I posit, is the juxtaposition existing between the mercantile and the divine. Around the early nineteen-nineties, Simpson, by then a photographer contributing to magazines whose creations had graced the pages of Vogue, the Village Voice, Unique NY, and an array of other renowned style publications, amplified her experiments in the fine-art sphere, positioning subjects akin to pinups—Jet Beauty of the Week poses—subsequently countering their transparency by integrating those masks. The masks do not invoke reflections regarding the authenticity of the homeland, intrinsically, but instead, thoughts of the shops uptown, where they, or imitations of their truer forms, are peddled. Thus, we observe the nudes experiencing electrifying, intricate sentiments, feelings transcending simplified notions of glorification and adulation of the woman who has endured disparagement historically in the realm of visual culture.

“Black Girl with Eye,” 1991 / 2021.

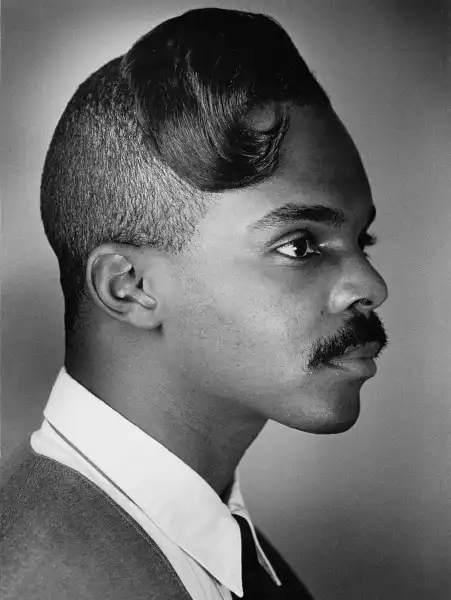

“Man with Curl,” ca. 1990s.

I viewed Simpson’s collection in 2022, hosted at Fotografiska, in New York City. The Nigerian British curator Aindrea Emelife had assembled an exposition destined to tour the diaspora, titled “Black Venus.” Almost at once, it became clear that the Enlightenment alongside its double standards, its classification of ethnicities, served as a target. Archival findings hailing from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries set the stage for the modern instances, all extracted from the nineteen-seventies through the present day, positioned as ripostes directed toward three historical Venuses: the Sable Venus, the Hottentot Venus, in addition to Josephine Baker embodied as a jezebel. Adjacent to Simpson’s masked women, Emelife had united works crafted by Renée Cox, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Kara Walker, Mickalene Thomas, Widline Cadet, Ming Smith, coupled with myriad others. Coreen Simpson’s visuals resonated profoundly within me, partially on the basis that while unfamiliar, they evoked a sense of familiarity.

“Toni Morrison,” 1978.

“Ming Smith, New York,” 1983.

“Dr. Nina Simone,” ca. 1991.

Could it be attributed to her amorous parlance existing within intimate dialogue alongside street vernacular? Could it stem from her direct compositions pertaining to human inclination and disparity reminding me of Diane Arbus? One discerns, when faced with her artistic works, that a negligible divide separates the photographer from her subjects, in spite of her endeavoring to anonymize them to our gaze. One hoped, while traversing through the gallery, that Simpson had been afforded the prospect to capture that alleged jezebel, the star Baker. They embody the type of women who possessed comprehension regarding the prowess inherent in masking. What actions would she have pursued when faced with the woman who naturally bore her brown complexion though chose to navigate a perilous existence steeped in political covert operations, who skillfully harnessed the French negrophilic tendency, who remained cognizant of the protective nature masks may provide the soul residing within? I hungered to glean further insights into Simpson and her apparent rapport to perceiving and to overlooking. It surprised me to discover that Simpson had experienced abandonment at the hands of her progenitors, who together encapsulated the binary extremes composing quintessential New York ethnic distinction: the Jewish pedagogue mother, coupled with the Black jazz-performer father. It surprised me to ascertain that Simpson harbored as her personal icon representing beauty the social aide from her earlier years, a woman bearing a deeply hued complexion addressed as Miss Foster. Learning that Simpson had engaged in some amount of modeling did not particularly shock me, given her inherent beauty, however, I found myself musing on how her encounters whilst stationed prior to the camera might have influenced her philosophy existing beyond it.

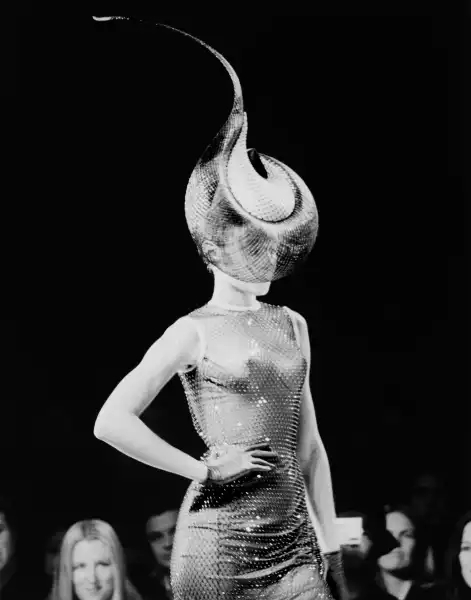

“Unknown Model Wearing a Philip Treacy Hat,” 1989.

“Untitled,” 1979.

Simpson, coincidentally, at one time released a personal conviction. Senga Nengudi and Charles Abramson, the organizers directing “Joining Forces: 1+1=3,” an exposition dating to 1986 showcased at the New Muse Community Museum, found within Brooklyn, coupled with Gallery 1199, positioned in Manhattan, called upon Simpson to compose representations of their artists, who had undergone organization through hetero pairings throughout an experiment regarding co-creation. Throughout the exposition text, Simpson articulates numerous spirits paying her visits while she remains within the room fabricating a photograph: the “Spirit of Anger,” the intertwined entities of “Mystery and Metaphysics.” One among them to which we could devote attention entails that of “Vulnerability,” by no means something mundane. Simpson elucidates: “She isn’t fond of the world bearing witness to her, furthermore, the other spirits affected an ignorance toward her existence though she disregarded them and proved to be truly one of the most stimulating spirits.” It strikes one almost subconsciously, the affiliation we render photography with revelation. Her labor opens, plus it holds charisma, nonetheless, Simpson remains additionally a historian pertaining to what it means when engaging in acts of concealment. She grants us glimpses of her subjects, though prevents us from truly knowing their essence.

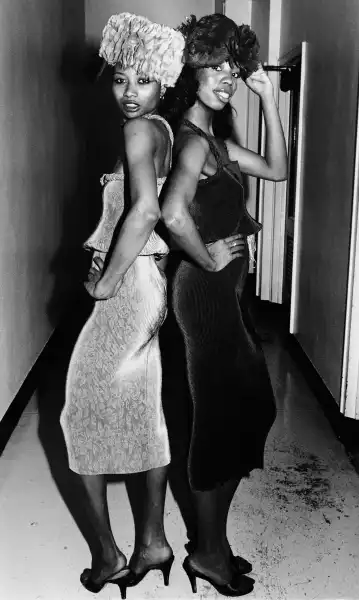

“City People,” 1976.

The masked nude takes the form of a vibrant collage. Simpson registers as a true multidisciplinarian; upon achieving mastery over one medium, she senses an attraction directing her toward pursuing familiarity regarding another. She serves as the surrealist, embodied via her layered portraiture, which manifest as fantasies evoking Man Ray and Romare Bearden, with thoughts directed at the body in the capacity of material. The dramatist Ntozake Shange, her visage superseded by an expansive, lavishly patterned mouth. A glamour snapshot featuring a man, his hairdo elegantly swept within the dandy configuration, inclusive of metal overtaking his profile. These modifications hint toward the physical manifestation that is the photographer herself, thereby imposing her being upon the image.

“Ntozake Shange,” 1997 / 2021.

Simpson may have gained the pinnacle of triumph spanning her career detached from the photographic realm, though never fully abandons the domain that encapsulates portraiture. The fragments comprising her Black Cameo Collection, Simpson’s jewelry series depicting silhouetted figures, carved within raised relief, could have plausibly graced the presences of the most recognized glamourous women, both Black and white. The cameos might undergo interpretation as physical objects, pieces which impart a subversion directed toward Victorian principles. (Who facilitated the generation of funds underwriting the bejeweled women defining the British Empire?) The woman showcased in profile displayed upon Simpson’s cameo artworks represents a Black woman adorned with black hair. She encompasses pure faciality, though we nevertheless remain ignorant of her truer essence. She materializes as yet another Venus.

“Gail Pilgrim wearing a Black Cameo Collection crown,” 1990s.

These images and the accompanying words originate from “Coreen Simpson: A Monograph,” a work issued by Aperture.

Sourse: newyorker.com