Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

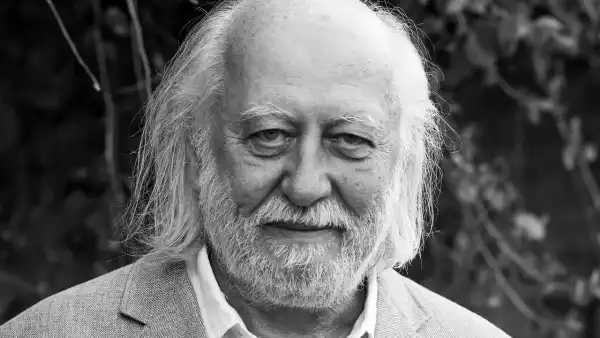

In 2011, I commented that delving into the writings of László Krasznahorkai “resembles observing a group of individuals clustered in a town plaza, ostensibly warming themselves by a blaze, only to realize, upon closer inspection, that there is no blaze, and that they are assembled around absolutely nothing.” For numerous typical readers, the prospect of immersing themselves in a fictional realm perpetually hovering on the brink of an unveiling that is constantly impending yet obscured, where words orbit endlessly around meaning, and whose favored device is the lengthy, unbroken sentence, one that might take, for instance, four hundred pages to unfold, could constitute—well, it could constitute precisely the sort of trembling instability that Krasznahorkai has depicted so skillfully and empathetically, for so many years. It could embody what he has termed “reality scrutinized to the threshold of derangement.”

Previously, merely two of Krasznahorkai’s novels were obtainable in English—“The Melancholy of Resistance” and “War and War,” which saw publication in Hungarian in 1989 and 1999, correspondingly. Krasznahorkai had already risen to fame in Europe, notably in Germany, where he resided and where the majority of his works were translated. In that locale, it was conventional to hear him regarded as a probable future Nobel recipient, but, with such limited material available in English, such conjectures possessed the quality of courtly hearsay. Nonetheless, “The Melancholy of Resistance” was circulated like premium underground literature. It was of Hungarian origin; it boasted a magnificent, somberly bombastic title (suggesting insightfully both the significance of resistance and its certain depletion); and it received accolades from W. G. Sebald and Susan Sontag.

Apart from the pair of translated books, there existed alluring glimpses of other works. Krasznahorkai’s initial novel, “Sátántangó,” dating back to 1985, remained absent from English translation, but one could view Béla Tarr’s seven-hour film adaptation bearing the same title. (Krasznahorkai has authored scripts for six of Tarr’s cinematic endeavors.) I had perhaps viewed two hours of “Sátántangó” but, until the English rendition, courtesy of the poet George Szirtes, ultimately materialized, I could only envision the spiraling yet comprehensible meandering sentences that Tarr’s extended tracking shots were presumably striving to replicate cinematically:

The physician was positioned near the aperture, experiencing melancholy, his shoulder pressed against the frigid, damp wall, and he was not even required to adjust his head to observe the estate through the space between the soiled floral curtain passed down from his mother and the decaying window frame; he merely had to elevate his gaze from his book, cast a fleeting glance to note the slightest variation, and if it occasionally transpired—say, if he was utterly engrossed in contemplation or because he had concentrated on one of the most remote points of the estate—that his eyes overlooked something, his remarkably acute ears instantly came to his rescue, although it was infrequent for him to be immersed in thought and even rarer for him to arise, clad in his fur-collared winter coat, from the heavily blanketed, upholstered armchair—its location meticulously dictated by the accumulated familiarity of his daily activities, successfully diminishing to a minimum the number of possible instances in which he would be compelled to vacate his observation post by the aperture.

Readers of the English language were starting to close the gap, as a surge of exceptional works surfaced in translation, corroborating Krasznahorkai’s expertise: “Seiobo There Below” (2013), “Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming” (2019), and, most recently, “Herscht 07769” (2024), arguably the most approachable of his novels. (All of the recent fiction has been rendered into flowing, winding English by the outstanding Canadian translator Ottilie Mulzet.) Each represents an unparalleled and unique creation, and each broadens Krasznahorkai’s scope. “Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming,” for instance, presents a tragicomic, idealistic clash between the disheartened and xenophobic denizens of a run-down provincial Hungarian municipality and a returning expatriate nobleman, the Baron Béla Wenckheim of the title, in whom they have reposed their (frequently reactionary) aspirations. Yet the returning aristocrat is a worn-out spendthrift, and will discover no sanctuary or absolution from his bickering and inbred compatriots. The novel serves as a reminder of Krasznahorkai’s capacity for humor. “Eternity—will last as long as it lasts” is the novel’s amusing epigraph.

Nevertheless, in certain respects, those initial two novels that I perused back in 2011 establish the distinctive ambiance of much of the subsequent work: the uncertain politics of minor towns in Hungary and the former East Germany (nativists, neo-Nazis, upholders of law and order); an uneasy premonition of impending doom, both political and metaphysical; and Krasznahorkai’s partiality for prophetic obsessives and simpletons (a global authority on mosses, an archivist convinced of the discovery of a long-forgotten manuscript who journeys to New York to disseminate its existence, a pianist fixated on the precise tuning of the piano). Despite outward appearances to the contrary—the spiraling sentences, the fervent intellectualizing—there exists nothing reclusive about Krasznahorkai’s oeuvre, both established and emergent, which confronts directly contemporary European actuality and its hazards, encompassing the agonizing dynamics of settlement, mobility, and identity.

For prospective readers, all of this can perhaps be optimally encountered in Krasznahorkai’s most recent novel, “Herscht 07769,” concerning an outsized yet, in his individual manner, perfectly unremarkable man, Florian Herscht, who resides in a small Thuringian town, in former East Germany, and whose occupation entails removing graffiti from the town’s communal structures. Herscht resembles some inspired yet perplexed fusion of Saul Bellow’s Herzog, Thomas Bernhard’s Wertheimer, and Hanta, the secluded narrator of Bohumil Hrabal’s novel “Too Loud a Solitude” (1976), whose duty involves compacting wastepaper and ancient books. Herscht has embraced the notion that an accumulation of antimatter is somehow destined to obliterate the world, and he concludes that the individual best equipped to address his concerns is the German Chancellor (and former physicist and quantum chemist) Angela Merkel. To her, he initiates the composition of lengthy letters that remain profoundly unanswered, endorsed with his surname and postal code: Herscht 07769.

Bellow, naturally, was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1976; Bernhard and Hrabal ought to have received it. But at least the Academy rectified the oversight with Krasznahorkai. May his accolade garner him numerous readers. For those among us already initiated into the curious and wondrous realm of his fiction, the pronouncement of his triumph in securing this year’s Nobel Prize for Literature evokes no substantial astonishment. Indeed, it manifests as something unequivocally equitable, akin to a well-earned libation at the culmination of a day’s strenuous exertion. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com