Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Amy Poehler could very well be the most beloved figure in Hollywood. Her most recent endeavor, the wildly popular podcast “Good Hang with Amy Poehler,” certainly fosters that idea. It’s possibly her largest platform since the celebrated show “Parks and Recreation,” where she embodied the enthusiastic civil servant Leslie Knope, concluded a decade ago. While numerous former castmates have explored new paths—Aziz Ansari by reimagining himself as a somber romantic character in “Master of None,” Adam Scott by showcasing his dramatic talents as a conflicted individual in “Severance”—Poehler has embraced Leslie’s essence: cheerfulness, sincerity, an emphasis on female camaraderie, and straightforward feminist principles. These traits are abundantly clear in “Good Hang,” which debuted in March and rapidly climbed to the top of the rankings, despite a heavily populated market. At one juncture, it unseated “The Joe Rogan Experience” as Spotify’s top program.

Like “Rogan,” “Good Hang” is a video podcast; Poehler engages in conversations with one or two celebrities each week, seated across from them at a light-wood table. The relaxed intimacy of her interactions with famous acquaintances is an undeniable component of the program’s allure. She employs affectionate names for her longtime friends: Tina Fey is “Betty,” Kathryn Hahn is “Hahnsy,” Rashida Jones is “Bones.” Occasionally, she touches a guest’s hand. “Good Hang” is undoubtedly curated, but the established rapport between Poehler and many of her guests contributes to the authenticity of the discussions and can lead to genuinely impactful moments. After Aubrey Plaza’s husband passed away by suicide, she openly discussed the tragedy for the first time on the podcast. Plaza, who has known Poehler for nearly her entire professional journey, abandoned her usual enigmatic persona and openly shared her experience with the “vast sea of horror” that is widowhood. Andy Samberg also spoke freely about his sorrow following the passing of his “Brooklyn Nine-Nine” co-star, Andre Braugher. In fact, Poehler is so disarming that several interviewees—Seth Meyers, the creators of “Broad City,” Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson—have become emotional while expressing the importance of her support.

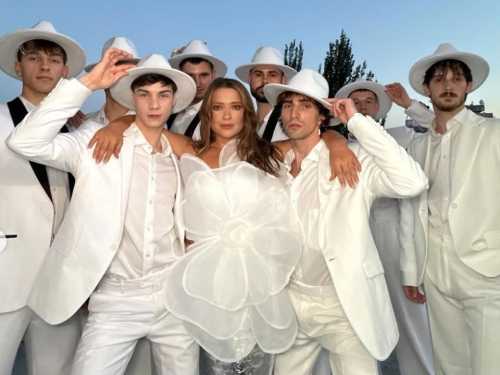

Besides these emotional instances, Poehler intentionally maintains a lighthearted atmosphere, and the show’s visual style reflects her desire to create a comfortable environment for her guests. The studio features welcoming, millennial-inspired details: artificial plants, luminous signage, and pastel hues. It resembles the kind of startup environment where employees are encouraged to bring their pets, even though Poehler, who believes that “rules make things enjoyable,” is firmly against animals in the workplace. (Dakota Johnson and Plaza disregarded this rule and brought their pets.)

Poehler appears to have drawn inspiration from audiences’ renewed fondness for “Parks and Rec” as a source of comfort during the pandemic—a phenomenon she mentions repeatedly—and it’s easy to observe the connection between the series and the podcast. “Parks” was a workplace comedy characterized by its faith in people’s ability to evolve, and on “Good Hang,” celebrities frequently reminisce about their early, and therefore most relatable, experiences. There are frequent, if standard, tributes to female unity, reminiscent of Galentine’s Day, the holiday Leslie created to celebrate the women in her life, and each episode begins with Poehler calling a guest’s loved ones to “speak kindly” behind their back. The intention is supposedly to aid in formulating questions; mostly, it serves as an opportunity to praise the featured woman or man. (Jeremy O. Harris on Natasha Lyonne: “This, like, unrestrained intelligence and unrestrained generosity merged into this atomic bomb of the perfect friend.”) All this adulation seems genuine—a take on the overly specific, nearly surreal praise that Leslie bestowed upon her best friend, Ann. However, the constant positive energy, like the exaggerated praise culture of Hollywood in general, can become irritating.

“Good Hang” is cognizant of its own superficiality. In the initial episode, Poehler builds a feminist argument for her lighthearted approach: she asserts that women are expected to be selfless and wise, and to speak out about issues like menopause, while men—presumably the hosts of other celebrity-on-celebrity interview podcasts, such as “Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend,” Dax Shepherd’s “Armchair Expert,” and Will Arnett, Sean Hayes, and Jason Bateman’s “Smartless”—are commended for simply engaging in casual conversation. Poehler isn’t a journalist, and this reality is both a strength and a weakness for the show. Her professional network and insights can be advantageous; the most compelling episodes feature kindred spirits like Quinta Brunson, with whom Poehler discusses, for instance, the unfair pressure on female writers and actors to represent their communities in ways that are both realistic and inspirational. She also secures extended interviews with stars who generally avoid the press, including Fey and Kristen Wiig. However, unlike a reporter, she will steer clear of delicate subjects with someone who prefers to avoid them. (Lyonne appeared on the show shortly after a story about her generative-A.I. studio generated significant controversy; Poehler, who consistently discusses new projects with guests, avoids mentioning the endeavor.)

Much attention has been directed toward the possibility that traditional late-night television may soon be overtaken by podcasts and gimmick-driven series like “Hot Ones” and “Chicken Shop Date,” which have been celebrated for eliciting “genuine” responses from media-savvy celebrities. On Poehler’s program, however, a clear distinction exists between the stars she already knows and those she doesn’t. Her “yes, and . . .” approach, perfected over decades as a sketch comedian, makes her an adaptable conversationalist, but it’s not always enough to engage actors who are merely fulfilling promotional obligations. The obligatory lightheartedness ensures that some of these discussions never move beyond trivial chatter. I could easily go on without ever hearing Poehler ask another guest about their sleeping habits, much less directing such questions at Michelle Obama.

Still, the hour-long duration of “Good Hang”—a noticeable contrast to the seven or eight minutes allotted to celebrities on a late-night sofa between commercial breaks—serves as a reminder that even A-listers require time to become comfortable. There’s a certain appeal to the spectacle of their ease. If a risk-free, stars-only sanctuary is the only means of seeing them in a more authentic state, it seems to be a compromise that millions are willing to accept. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com