Erik ten Hag says he would never gamble with a player’s fitness as injury-hit Manchester United limp into Sunday’s crunch clash with Arsenal.

The Red Devils have been beset by issues during a bumpy campaign that leaves them fighting for European qualification and to avoid recording their worst ever Premier League finish.

Bruno Fernandes, Marcus Rashford and Scott McTominay could return to the fold when United host title-chasing Arsenal, although a swathe of players remain unavailable.

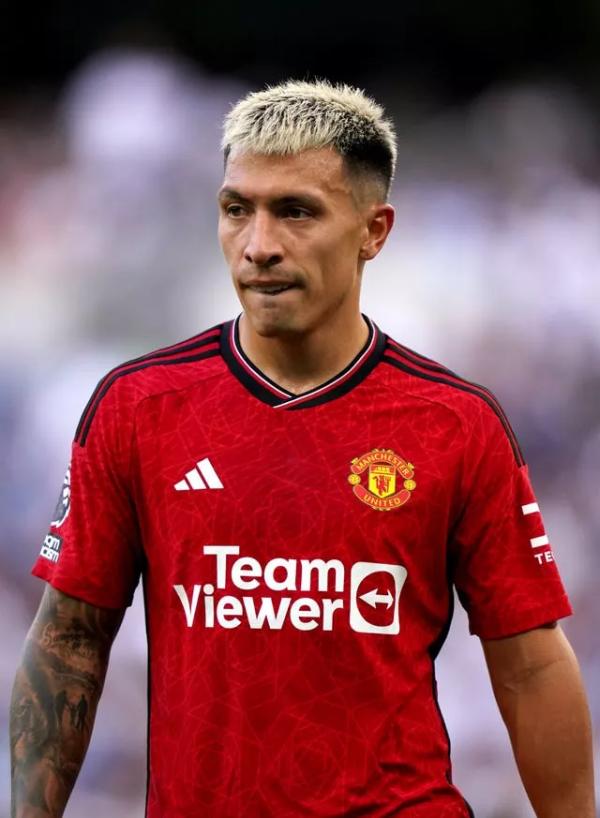

Lisandro Martinez is among the absentees but pleaded with Ten Hag to let him play on Sunday, but the manager says he will not rush him back despite his backline being as porous as it is patchy.

“He is desperate to play, he misses so much,” the United manager said. “The team missed him and he wants to play.

“But he had three injuries across the season and now he’s almost there, so injury free, so he’s in the end of the healing process and now he has to get back into team training, into matches.

“I will never do a gamble with a player. Never.

“It’s about them, it’s about their futures. That’s the most important, about their careers. I have to take responsibility for it.

“Of course the club is the most important but the safety from the player, the health of the player, I think that is also always a higher level.”

Martinez should be back from his calf issue before the FA Cup final against Manchester City, but remains sidelined with fellow centre-backs Harry Maguire, Victor Lindelof, Raphael Varane and Willy Kambwala.

Left-backs Luke Shaw – who Ten Hag revealed has suffered a setback – and Tyrell Malacia also remain absent from an unbalanced backline punished 4-0 by Crystal Palace on Monday.

Now the Premier League’s most potent attack is coming to Old Trafford as Arsenal continue their fight with reigning champions City for the crown.

“We always go in a game to win, not preparing for the next game,” Ten Hag said.

“Of course (the FA Cup final) is in the back of my mind, but we want to put a team on Sunday that is competitive, a team that is eager to win and we choose the best team for Sunday to win that game.

“Arsenal are one of the best teams, or probably the best team. You can discuss about this – is City the best team or is Arsenal at this moment the best team?

“Very ball secure, so very good structures. We know we have to play to absolutely our maximum levels to get a result in, but we are capable of it.”

Asked what he says to fans who think United have no chance after the Palace performance, the United boss said: “You see the fans on Monday, they were our example. That is what I told the players.

“They backed us and I think they see how we struggle, they see our problems, so they have a very good understanding about all the injuries we have, that we struggle.

“But they keep backing the team, so I am very pleased with them.”

Sourse: breakingnews.ie