Share

Tweet

Share

Share

I didn’t read Harry Potter when I was growing up. And I wasn’t alone.

tweet

share

So what if you didn’t grow up immersed in the wizarding world of Harry Potter?

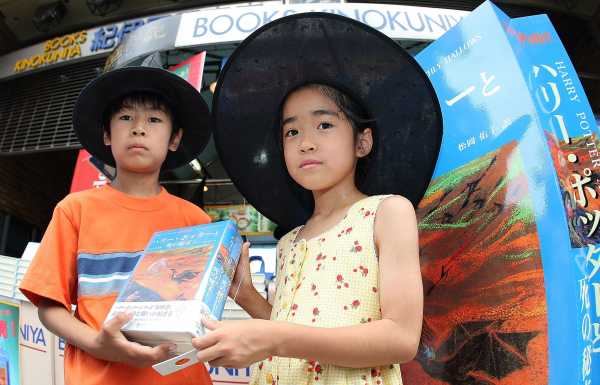

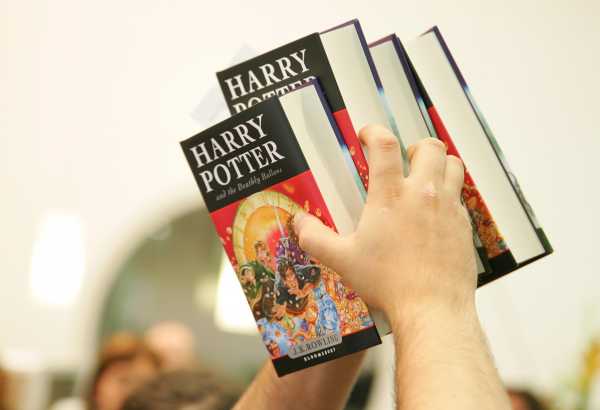

For plenty of Americans — especially millennials, who were children when the books first came to the US — that’s an almost unimaginable hypothetical. The books shaped the imagination of millions of children, who flocked to midnight release parties, dressed as Harry and Hermione and Ron for Halloween, watched the movies, and even now frame their understanding of real-world political events in terms of Hogwarts and He Who Must Not Be Named.

But a sizable chunk of the same age cohort didn’t read the books at all.

That wasn’t because they just weren’t into books, or because they didn’t know about Harry Potter. It was because in some religious communities — particularly among conservative evangelicals, but also some Catholics and Muslims — the Harry Potter series was viewed on a spectrum that ranged from suspicion to outright opposition.

To some, the reasons may be obvious; to others, that makes no sense. But the phenomenon of conservative Christian opposition to Harry Potter succinctly encapsulates many of the forces that were at play within that group two decades ago — and illuminates a whole group of young adults who felt excluded from the world around them.

One of the biggest sources of Harry Potter opposition came from Focus on the Family

I’m among the millennials who grew up not reading J.K. Rowling’s novels or watching the films for religious reasons. While writing this article, I’ve had hundreds of conversations through social media and in person with adults across the country who had the same experience.

For many of us, reading the novels wasn’t outright forbidden, at least not through some kind of household decree; it was just understood that it wasn’t something we did in our homes. (I’d fall into this category.) For others, the opposition was much more overt. Some people spoke to me about bringing home the novels and having them taken away. Others felt ashamed about times when their parents told their teachers that they wouldn’t be allowed to read the books along with the rest of the class.

The variety of these experiences helps illuminate the complexity of opposition to Harry Potter’s world — something that’s been bolstered as I’ve talked to parents who once opposed the books and have changed their views, and others who still prefer not to let their children read them.

Many of us non-readers found that our parents’ opposition to Harry Potter dropped away as we got older, or as the series was completed and its overt Christian influences became clearer — and then were confirmed in 2007 by Rowling herself, who told MTV in an interview that she thought the Christian symbolism had been obvious. Still, others I’ve talked to say their parents continue to oppose the novels, even removing them from their adult children’s shelves if they move home.

To those who grew up with the books, that may seem slightly baffling. The stories of Hogwarts and the young wizards seem of a piece, in many ways, with the battles of good and evil contained in other classic works of fantasy, including some explicitly Christian-influenced ones such as C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia and J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. So what accounts for this opposition?

The answer has a lot to do with some of the voices that were especially influential in conservative Christian culture, and especially evangelical culture, in the late 1990s and 2000s, when Harry Potter was growing into a literary phenomenon.

The most often cited voice of opposition among those I talked to was Focus on the Family, an immensely popular and influential evangelical parachurch operation, and in particular the organization’s leader until 2003, author and psychologist James Dobson.

Dobson rose to prominence as a proponent of conservative social positions and relatively strict child-rearing practices. He founded his flagship organization, Focus on the Family, in 1977, and produced a daily radio show by the same name that at its height was reportedly heard every day by more than 220 million people in 164 countries and in a dozen languages.

Focus on the Family is especially influential in telling conservative evangelical parents how to navigate popular culture, which it does in two ways. It creates pop culture of its own, combining entertaining stories that teach biblical lessons with relatively high production values — the long-running fictional radio drama Adventures in Odyssey is an especially successful example — as an alternative to mainstream entertainment. And it produces a publication called Plugged In, which describes itself as “an entertainment guide full of the reviews you need to make wise personal and family-friendly decisions about movies, videos, music, TV, games and books.”

Plugged In is hardly the only publication that does this — Christianity Today, where I was chief film critic before joining Vox in 2016, has done it for years, as have far more conservative sites like MovieGuide — but it’s one of the longest-running and most popular in existence, partly due to its backing by Focus.

Plugged In reviews were a fixture of life for many children growing up in conservative evangelical churches, particularly in the 1990s. Unlike some more hardline Christian review sites, Plugged In reviewers often comment generously on the artistic and technical value of a pop artist’s debut album or the latest franchise blockbuster. But they also describe, in some detail, the moral content of the cultural object and make recommendations based on those matters, outlining everything from spiritual elements to violent content to drug and alcohol use.

The Plugged In review of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone is fairly typical of the site. It mentions among its positive elements Harry and Ron’s friendship, warnings against greed, and the sacrificial love of Harry’s parents. It points out the story’s use of rule-breaking and violent content, along with Hagrid’s taste for butterbeer. And it devotes three measured paragraphs to the “stereotypical” presentation of witchcraft and wizardry in the book, and suggests the way dark magic is portrayed does not make it seem desirable — all, on balance, good things, from a Plugged In perspective.

But the review also taps into what became the biggest opposition to the world of Hogwarts.

“On a cultural level, Rowling can be commended for steering young fans away from the so-called dark side,” the review adds parenthetically. “But from a spiritual perspective” — meaning, in the real world outside the books, according to the Bible — “it’s clear that there are not dark and light sides when it comes to witchcraft; it’s all as black as sin.”

In other words, though in the world of Harry Potter, magic can be used for good, in our world, governed by the rules of God and not fictional magic, all witchcraft is evil.

“The meaningless charms found in this book may not summon occult forces, but there are real charms that do,” the review suggests, and says that because the world of magic that Rowling has created is so much brighter and more interesting than the boring realm of Muggles, the books may hold an allure that is unhealthy for children. “Biblically speaking, to participate in the world of witchcraft brings death rather than a fuller life,” the review’s uncredited author writes.

In the end, while Plugged In praised the books in some modest respects, it also concluded that parents should “think long and hard before embarking on Harry Potter’s magic carpet ride.”

And that attitude of suspicion toward the Harry Potter books’ magic — and the worry that it would attract children to the occult — is perhaps the single most influential source of opposition to the series among conservative Christians.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most prominent voice in this opposition was James Dobson himself. He addressed the matter on his radio program and issued a lengthy response to an erroneous assertion in a 2007 Washington Post article that characterized him as having “praised” the series. A response posted to Focus on the Family’s website stated that “this is the exact opposite of Dr. Dobson’s opinion — in fact, he said a few years ago on his daily radio broadcast that ‘We have spoken out strongly against all of the Harry Potter products,’” and that the Post reporter had not just acknowledged but “apologized for” the error.

The statement also reiterated Dobson’s opposition to the series: “Given the trend toward witchcraft and New Age ideology in the larger culture, it’s difficult to ignore the effects such stories (albeit imaginary) might have on young, impressionable minds.”

Some conservative Christians opposed Harry Potter as a gateway to the occult. Others sounded a note of caution.

Dobson was far from the only conservative Christian leader who sounded a warning about the books. Just a quick Google search turns up articles, books, websites, and other resources warning families away from the books and movies because of their connection to witchcraft. A Jack Chick tract called “The Nervous Witch,” about Wicca and witchcraft, even features a character who says she got into “the craft” through the Harry Potter books.

Related

Satan, the pope, and Dungeons & Dragons: how Jack Chick’s cartoons informed American fundamentalism

In several states, parents sought to have the books removed from schools, suggesting in some cases that they were connected to Wicca and thus their inclusion in school libraries violated the separation of church and state.

Others, however, were more measured than Dobson and those who suggested Christian families shun the books.

Chuck Colson, the former Nixon administration official who became an evangelical leader, initially praised the books on his own radio broadcast in 1999. “If your kids do develop a taste for Harry Potter and his wizard friends,” Colson said, “this interest might just open them up to an appreciation for other fantasy books with a distinctly Christian worldview.”

But seven years later, he had changed his mind without going so far as to outright decry them; he said that while he didn’t personally recommend the books or movies to Christian families, they were a good opportunity to teach children to exercise discernment — that is, to examine them critically through the lens of their faith.

The conservative newsmagazine World, which regularly published reviews of the books and the movies as they were released, took a similar tone. In a piece titled “More Clay Than Potter,” published in 1999, World’s book critic Susan Olasky and Anne McCain, a director of children’s education at a Presbyterian church in Virginia, examined how the newly popular books “can give Bible-conscious parents an enjoyable opportunity to teach older children how to think critically.”

“Truths sprinkled throughout the books are ‘trail markers’ that can be used to point to God,” Olasky and McCain wrote, pointing to the books’ emphasis on wise counsel and the difference between good and evil as positive — while also noting that the books may put “a smiling mask on evil” and draw readers into the real world of witchcraft, though the Hogwarts world of wizardry bore little resemblance to the world of Wicca.

World’s reviews of the books and movies continued to be mixed through the end of the series, often noting the increasingly dark tone and the ways the moral order in Harry’s world may confuse children about the moral order in our own.

When I spoke with Olasky about World’s take on the series, she pointed to the magazine’s often mixed opinions on the books and movies, saying that their main concerns had a lot to do with simply not knowing where the series was going — especially since they dealt so powerfully with good and evil.

“It was a world that kids were drawn to,” she said. “But you didn’t really know [at first] what the rules were. … A thing would appear to be this, and then it would turn into that.”

That was also of concern to the parents who read World, and to those inclined to carefully watch over what their children experienced. “I still think Christians should think about that,” she said. “Should anything capture our imaginations like that?’

To Olasky and other critics who saw the series from her perspective, the world of Harry Potter wasn’t necessarily dangerous because it was a throughput to witchcraft, Satanism, and the occult. They were more concerned with the ideas that impressionable children might absorb from the immensely popular book, ideas that might conflict with biblical ideas about good, evil, light, darkness, obedience, and other matters. And they were concerned with reminding parents not to allow their children to uncritically accept stories just because they were popular — especially without knowing where the series was headed.

That perspective, which sought to protect children’s developing imaginations from particular content, seemed obviously false to others. YA author Judy Blume, for instance, wrote a dismissive op-ed titled “Is Harry Potter Evil?” in the New York Times in 1999, linking opposition to the books to efforts to ban books ranging from Madeleine L’Engle’s overtly Christian A Wrinkle in Time series to Blume’s own novels from school libraries. Blume praised “subversive” books for the ways they developed her imagination.

But to more protective parents, it made sense. And even those who might not take a hardline view against the books might have been inclined to avoid them, hearing the voice of alarm. That’s how communities that form around shared values, like religious or other beliefs, often work: In concert, they form practices and boundaries, and then support one another in maintaining those boundaries.

Not all conservative Christians opposed Harry Potter

There were also plenty of conservative Christian critics and leaders who leaned positive or outright supportive of the series from the start. One such Christian writer, John Granger — who was described in Time in 2009 as the “dean of Harry Potter scholars” — has written extensively about the series’ connection to Christian teachings in books such as Hidden Key to Harry Potter (now titled How Harry Cast His Spell) and Looking for God in Harry Potter. He also maintains the “Hogwarts Professor” blog.

Granger wrote his books in response to anti-Potter books, such as Richard Abanes’s Harry Potter and the Bible: The Menace Behind the Magic and Connie Neal’s What’s a Christian to Do About Harry Potter.

“The Christian content and continuity with English literature traditions were missing from both books,” Granger wrote to me by email. “I thought … that this symbolism interweaved in the storytelling was largely responsible for the series’ success.” Granger points to links present in the very first book: “A unicorn, a phoenix, a red lion, a Philosopher’s Stone, and a hero rising from the dead after a sacrificial death are all in the first book. All are traditional symbols of Christ.”

When I asked Granger why he thought conservative Christians opposed the book, he said the series’ use of magic suggested to some that there had to be some kind of conflict between the books and faith. “I received some dismissive and patronizing criticism,” he wrote, but “Christian critics largely left me alone because, unlike Abanes and Neal, I argued from English literature and formalist analysis rather than through a biblical filter.”

“Fortunately, all my ideas and understanding were confirmed by the last three books, especially Deathly Hallows,” Granger said.

Granger, and many others like him, came out in favor of the books. Christianity Today, which has often been considered the flagship publication of the American evangelical movement, published articles on both sides of the issue but generally took a more positive stance. Some saw the stories — particularly after its conclusion, in which Harry seems to be cast fairly obviously as a Christ figure — as reflecting the biblical story.

Still, the reasons for criticizing the series among those conservative Christians boiled down to two main camps. There were those who condemned the books as conduits to witchcraft, and there were those who viewed them skeptically as being influenced by secularism, potentially undermining Christian values.

There were good reasons both of those camps were so influential, even among those who didn’t read the books themselves, and they have a lot to do with the timing of The Sorcerer’s Stone’s US release, 20 years ago.

The Satanic panic and stories circulating in evangelical Christians subculture may have bolstered opposition to Harry Potter

In my discussions with those who weren’t allowed to read the books, or who didn’t allow their children to read the books, the idea that the books’ use of magic was tied to the real-world occult seemed strange to many in retrospect, for one big reason: Many of those same children were allowed, even encouraged, to read C.S. Lewis’s Narnia series as well as J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings series. (Some people who grew up in very fundamentalist communities said that even those were off limits, but that seems to be a minority.)

And yet there are a few cultural reasons this particular criticism caught on so powerfully. Most would require a whole book to thoroughly unpack, but two in particular are notable.

First of all, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone was released in the US in 1998 — right on the heels of the Satanic panic.

A rash of false allegations of Satanic ritual abuse of children by cults, made mostly against day care centers during the 1980s, were already being debunked during the ’90s. But the memory of those accusations was still fresh in the minds of many, especially since it continued to be a pop cultural plot point in TV shows and movies.

The lingering sense that some of it could have been true stuck around for years, subconsciously lending plausibility to the idea that Harry Potter and his friends were a subtle attempt to induct children into Satan-worshipping cults or witchcraft-practicing covens. (The common conflation of Satanic worship, the Church of Satan, pagan religions, the occult, witchcraft, and other systems of practice and belief was likely part of this.) The Jack Chick tract referenced above — published in 2002! — is a good example of how the ideas behind the Satanic panic were still alive in some of Christianity’s more fundamentalist wings.

Related

The history of Satanic Panic in the US — and why it’s not over yet

Another reason that Satanic panic-adjacent ideas still held currency by the end of the 1990s may be a pair of popular novels by Christian author Frank Peretti that sold millions of copies: This Present Darkness (1986) and Piercing the Darkness (1989). Both novels told stories of spiritual warfare in which angels and demons were literal characters struggling for the souls of ordinary Americans in a small town.

The books paid particular attention to New Age spiritual practices: Meditation was portrayed as a way for people to become possessed by demons, insidiously pushed upon people by a powerful New Age group that engaged in practices that seem drawn from accounts of Satanic groups. And their special target was children.

It would be a stretch to say that Peretti’s novels were responsible in some way for people’s suspicions of the Harry Potter books. But given their enduring popularity — I checked them out of my own church’s library and read them as a young teen in the mid- to late ’90s — their suggestion that children’s susceptible minds were targets for New Age groups covering for demonic forces certainly supported the idea that a series of fantasy novels for children had the potential to harm those children.

And even setting aside the more literalist takes on the occult contained in Peretti’s novels, there’s another factor; books like This Present Darkness, Piercing the Darkness, and the 1992 follow-up Prophet (in which a TV news anchor becomes embroiled in a controversial investigation of a local abortion clinic) spiritualized the culture war that evangelicals in particular were attuned to in the 1980s and ’90s.

That culture war — a battle to shape the values of young Americans through the things they see and experience in culture — has often been a source of fear and frustration for people across the religious and ideological spectrum over the past few decades. But conservative Christians are especially attuned to it, and Peretti’s novels (and others like them) gave the sense that the things you might watch on TV may not just change minds about “hot button” topics — sexuality, gender, abortion, and so on — but also be actual, literal battlegrounds between the forces of good and evil.

Even for parents who didn’t take this quite so literally, a more metaphorical notion of spiritual warfare exerted considerable influence over their decision about what to allow into their children’s lives.

I spoke about this with Nancy Gibson, a conservative evangelical mother who began homeschooling her children in the 2000s. Gibson’s older children didn’t read the Harry Potter novels as they were coming out — the family didn’t outright ban them, she said, but the communities they were part of discouraged people from reading them, mostly under the influence of Focus on the Family. But Gibson’s daughter read the series during the summer after her first year at a Christian college, and her younger daughter, now a teenager, has been reading them, with her parents’ approval.

Gibson told me that it was often simply difficult to know, as a parent in a community that was suspicious of popular culture, what was wise to allow their children to read. Resources like those provided by Plugged In helped navigate that challenge, particularly for those parents who didn’t have time to read the books for themselves.

Gibson’s experience seems aligned with those of many other parents, for whom navigating popular culture is difficult no matter what their religious convictions are. Some parents are more permissive, or are engaged with pop culture in a way that lets them experience it alongside their own children.

But conservative Christians and evangelicals in particular have for decades tended to view mainstream popular culture with suspicion. And in the throes of the late Satanic panic, raging culture wars, and the sense that — even aside from these forces — children were likely being targeted by people opposed to their own values, warnings against Harry Potter presented themselves as a good enough reason to stay away. There was, after all, always Narnia.

So what happened to those who didn’t read Harry Potter?

I’ve been reading Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone for the first time while working on this article. I know how the story goes, because by the time the movie series was reaching its conclusion, I was an adult and a working film critic, and I watched them all. (The third one, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, is the best of the bunch.)

But I’d never gotten around to the books, so now I’ve read the first in the series. News flash: It’s pretty delightful. I was surprised by the wit and by the clever characterizations, and I like the careful attention given to building out the world of both Muggles and wizards. I wouldn’t say I’m very invested in it, but it’s fun.

Would I have liked them if I’d read them when they first came out? Probably. In 1998 I was 15, a hopeless bookworm who didn’t watch many movies or TV shows but did read books like This Present Darkness. I had read and reread the Narnia series since I was in third or fourth grade, and I loved the movie versions that sometimes aired on PBS. I wasn’t into fantasy all that much, but Harry’s world feels enough like my own that I would have enjoyed them. And as a conservative Christian teenager, I probably would have found a lot to praise in them — just like many others did.

But I didn’t read them. And to my recollection, I never asked my parents to let me, either. Unlike some of my peers, for whom being excluded from Harry’s world meant being excluded from our age cohort’s most important obsession, I don’t really mind. For me, my never having read Harry Potter has always been a point of curiosity more than frustration, much like the fact that, until recently, I’d never seen Titanic. (There’s nudity and a sex scene!)

Many American millennials who grew up in conservative Christian families share plenty of these touchstones, things in pop culture we knew we shouldn’t watch or read or do, or things we thought we should engage with. The Simpsons was bad. A Walk to Remember was good. We kissed dating goodbye. Dungeons & Dragons, the Smurfs, and the Care Bears were bad, as were Cabbage Patch dolls (the rumor was that they were possessed by demons), but we probably read Left Behind. Plenty of young people got rid of their secular music and replaced it with Christian versions. A lot of us spent our evenings every October 31 at a church “harvest party” instead of trick-or-treating. Rejecting a lot of mainstream pop culture was part of who we were.

That speaks strongly, in many ways, to what it meant in the ’90s and 2000s to be a Christian kid or teenager. Many of our associations with our youth — particularly for those of us who grew up evangelical — are more tightly linked to the things in mainstream pop culture we weren’t allowed to experience than to religious experience itself. In banning things like Harry Potter or “secular” music, evangelicals often tried to create alternate cultural products to fill the void.

That tendency hasn’t died off, although there seems to be a higher tolerance among evangelicals and other conservative Christians today for engagement with mainstream secular culture, less about the Plugged In style of tabulating objectionable content and more about analyzing and thinking critically about it.

Even so, a generation of conservative Christian millennials like me arrived at adulthood without having had the same pop culture experiences as many of our peers. Maybe that’s just a symptom of an increasingly niche-driven, fragmented popular culture. But for many I’ve talked to, it’s also a source of sorrow. They miss having had a basis for talking to their peers about something everyone enjoyed — and in the case of Harry Potter, for many, it seems that the thing they were barred from might have, in the end, been one of the most Christian stories produced by mainstream culture in a long time.

Sourse: vox.com