Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

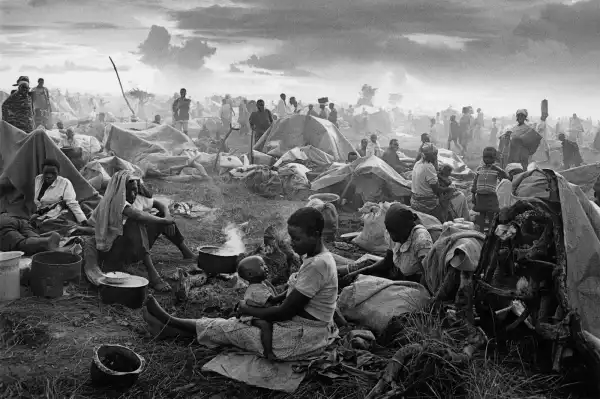

Sebastião Salgado, who died last week of leukemia at the age of 81, was one of the most celebrated documentary photographers of the 20th century. Over more than four decades of ambitious, globe-spanning projects, many of them both self-directed and largely self-financed, he created an instantly recognizable aesthetic in a field that typically eschews overt authorial intervention. His images were cinematic in quality, symbolically dense, and unashamedly beautiful, even when he was documenting some of the last century’s most horrific human tragedies, such as the Sahel famine of the mid-1980s or the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide. A key element of what Cornell Capa once called “concerned photography,” Salgado’s work earned him numerous prestigious awards and was featured in major traveling exhibitions and luxury coffee table books. Sandra Phillips, former senior curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, once described him as “one of the most important artists in the Western Hemisphere.”

Rwandan refugee camp, 1994. Photo by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

Salgado’s work has also had its share of controversy. Susan Sontag, in her final book, On the Pain of Others, called him “a photographer who specializes in the world’s suffering” whose work “has become a central target of a new campaign against the inauthenticity of beauty.” The critic and editor Ingrid Sischy wrote in a scathing 1991 article for The New Yorker that Salgado’s work was “oversimplified,” “heavy,” and ultimately ineffective. “To aestheticize tragedy,” she declared, “is the quickest way to anesthetize the senses of those who witness it. Beauty is a call to admiration, not to action.” How you feel about Salgado’s work may depend on whether you agree with that assertion. If you believe that difficult truths should be presented only in their rawest, simplest form (which is, of course, an artificial form), then Salgado’s powerful images are not for you. But if you believe, as I do, that most audiences are discerning enough to separate content from form, then Salgado's operatic style can be seen as a powerful enhancement to his testimony.

Sourse: newyorker.com