Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

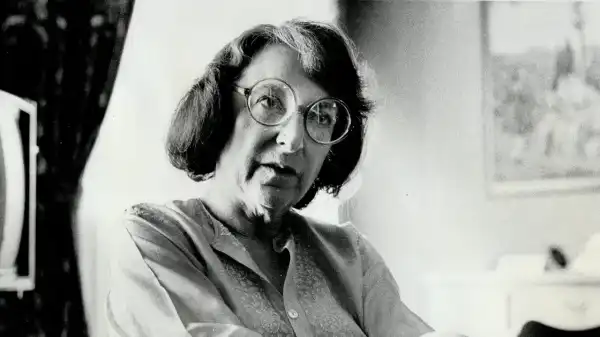

Pauline Kael’s most famous article for The New Yorker, her famous review of Bonnie and Clyde from October 1967, was the second piece she wrote for the publication. The first, published in June of that year, did not have the same impact but covered a broader topic that still matters to the film industry today. Entitled “Movies on Television,” the article covers Kael’s experience of watching movies at home, on cable, before the advent of VCRs and video rentals. It also goes beyond her personal perceptions to take a pessimistic view of the phenomenon of home moviegoing in general. While it contains many insightful observations about cinema and her own relationship with it, the article also contains a conservative and nostalgic tone that reflects an indifference to how younger generations experience movies. While “Movies on Television” is full of insightful observations, it demonstrates why Kael continues to exert a significant influence on film history more than half a century later.

Long before home video emerged in the 1980s, most people watched far more movies at home than they did in theaters. Movies became a key form of home entertainment beginning in the early 1950s, when they began to fill the airtime amid the early television boom. Television stations needed content to fill their programming, and movie studios had a plethora of old movies to play with. As Kale notes in her article “Movies on Television,” the movies shown on television were “old”—all of the titles she mentions were made at least a decade earlier, and most dated from the 1930s and 1940s. She examines the impact of television format on the reception of art, and her findings are not surprising: she finds that dialogue-heavy films (including the works of Preston Sturges and Joseph L. Mankiewicz) fare better on TV, as do horror films, while large-scale action or visually intense pictures (such as the works of Max Ophüls and Josef von Sternberg, or the “lyricism” of Satyajit Ray) do not. She also looks at the distortion of film formats to fit the near-square television screens of the time, the cuts to running times that were often made to fit into Procrustean time constraints, and the interruptions of commercials. (Kale was not alone in her criticism of this last aspect: Otto Preminger filed a lawsuit over commercial breaks in the broadcast of his 1959 film Anatomy of a Murder, and the suit became the basis for Lillian Ross's excellent New Yorker article, “Preminger's Profile.”)

What’s most striking about Kael’s article is her description of her own movie-going habits and interests, and how they intersected with the selection of films for broadcast. In most cases, studios sold films to networks and stations in bulk. With the exception of a few prestigious screenings, films were not selected for broadcast based on their merits but purchased in bulk. Networks thus offered a seemingly random selection of films, reminding Kael of how few were truly worth showing or even seeing for the first time—she recalls broadcasting certain films that “audiences abandoned thirty years ago.”

According to the Times TV listings for the date of the issue in which Kael’s article appeared (Saturday: The New Yorker’s issue dates were not changed to Mondays until the July 2, 1973, issue), the six major commercial networks were broadcasting twenty-three films released between 1934 and 1960. Some were standouts—Raoul Walsh’s Gentleman Jim, Billy Wilder’s Sabrina, and the Leo McCarey comedy The Six, with W. C. Fields. There was also an early (and dubbed) Ingmar Bergman film; a gritty melodrama, The Best of Everything; and a late-night thriller, Tarantula, a childhood favorite of mine—but most of the time was taken up by obscure journeymen or entries in past franchises (like Tarzan or Charlie Chan). Kael worried about these daily selections, believing that they decontextualized the films shown. She was forty-seven at the time of publication, and acutely aware of the difference between seeing films in their novelty and revisiting them, that is, viewing them outside their social context. Even the “junk” films of her youth mattered, she argued, because they “shaped our tastes and our experiences.” But, she continued, “these films now exist for new generations for whom they may not have the same impact or meaning because they are all jumbled together, out of historical sequence.”

This is certainly true, if only on a superficial level: discovering a work from the past is different from experiencing it directly at the moment of its release. But Kael uses this distinction to assert her primacy as a critical authority on “old” films solely on the basis of her age and experience. I recently revisited her extraordinary 1971 manifesto-like article, “Notes on Heart and Mind,” and found that she made a similar argument

Sourse: newyorker.com