Rick, a 54-year-old schoolteacher who lives in the Washington, DC, area, believes in American institutions. He voted for Hillary Clinton, he supports Obamacare, and he believes health care is a universal right.

“I think that’s what we’re supposed to be about as a country. I don’t know these guys from anybody,” he said, gesturing to the other people in the focus group we had convened. “But I would help them just as soon as I would help somebody in my family because of their humanity and mine, so there’s a shared humanity here that I think is supposed to be representative of what our nation is about.”

Democrats believe in health care. Barack Obama called it a “right,” and just last year, in the midst of efforts to repeal Obamacare, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) rolled out a revised version of his plan to go much further — universal single-payer health care. The Sanders Medicare-for-all plan was enormously popular with the progressive base and the Democratic Party’s top 2020 presidential contenders.

As single-payer health care gains currency in Democratic circles, opinion researcher Michael Perry gathered two focus groups of eight Clinton voters last fall to interrogate what ordinary, rank-and-file Democrats think about single-payer and other proposals to expand the Medicare program to more Americans. But surprisingly, some of these Democrats do not fully buy into a Medicare-for-all plan.

Blame Donald Trump.

Rick said he’s seen President Trump’s administration chip away at the Affordable Care Act after seizing power. His faith in the government’s ability to deliver dependable health care has been shaken.

“Before this particular administration, I had a lot more trust in the government, whether I agreed with what they had or not. I’m comfortable with a system that is run by the government, and I would have said that without equivocating,” Rick told us. “But right now, I’m a little bit iffy on it.”

He wasn’t alone.

“I was going to say the same thing,” said Ken, a 66-year-old consultant. “Which government? The rational American government the past three decades I feel pretty good about.” But Ken wasn’t so sure about Donald Trump’s government.

Trump’s election has left lots of liberals unmoored. They don’t have quite the same faith in democratic norms or institutions that they used to. The fact that Trump could be elected at all — and dispense with the parts of Obamacare he disagrees with — has shown them the fraying seams of our political system.

Democratic politicians are rallying behind Medicare-for-all

Americans are warming up to single-payer health care — and Democrats seem to be driving the trend.

Sanders made it a centerpiece of his insurgent campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016. This year, when he released the most detailed bill yet outlining what Medicare-for-all would actually look like, he got 16 Senate Democrats to sign on. They included some of the most prominent presumptive 2020 candidates for the White House: New York’s Kirsten Gillibrand, California’s Kamala Harris, Massachusetts’s Elizabeth Warren, and New Jersey’s Cory Booker.

Sanders’s bill would create a single government program that would insure every American. Employer insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid would be things of the past. The plan would cover almost every conceivable health care service, at almost no cost (with the exception of prescription drugs) to consumers. It is the most generous vision for single-payer health care in the developed world.

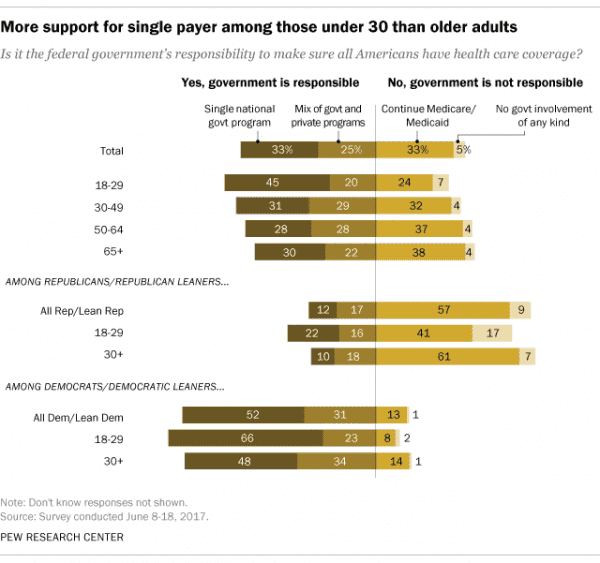

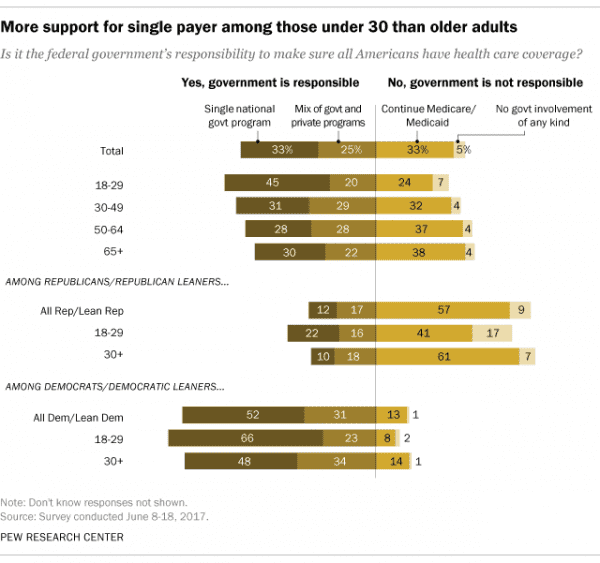

A look at polling shows young people in particular like the idea of government-run health care, a sign it may soon be a litmus test for any Democratic presidential candidate.

“When you say, ‘I’m for that,’ it says that ‘I’m for equity.’ It says, ‘I’m gonna fight back against the corporate establishment,” Robert Blendon, a professor of health policy and political analysis at Harvard University’s public health school, where he conducts polls on health care, told me recently. “They are not health care voters, but essentially it’s symbolic of these other things which appeal to young liberal people.”

Decaying trust in institutions is a real challenge to Medicare-for-all

A main selling point behind single-payer proposals like Medicare-for-all is that it is the government, not private for-profit companies, that is responsible for health care. Up until Trump’s election, that was a huge positive if you were on the left side of the political spectrum. Now, suburban Democratic voters who might be inclined to support single-payer are suddenly wary. They aren’t sure the government will ever be stable enough to be given responsibility for the entire nation’s health care.

“I wouldn’t trust any politician, not just Trump,” Elizabeth, 58, said. “I wouldn’t trust any politician because a political agenda is very different than an academic, research-based reason, scientific-based reason to make a decision.”

Trump himself is trying to lean into that anxiety. Earlier this week, he cited ongoing troubles with the United Kingdom’s universal health care program — which, to be clear, British experts attribute to poor funding rather than the system itself — to slam the Democratic ambitions of single-payer health care.

These arguments present a real challenge for the Democrats who want to pursue a Medicare-for-all system to provide health insurance to everyone and eliminate medical debt in the United States. They need to persuade people like Rick, Ken, and Elizabeth in the focus group — people who already believe health care is a human right — that the federal government can be trusted to oversee it.

Right now, those people aren’t quite buying it.

Which helps explain why polling experts express caution on single-payer. While Americans might broadly support universal, government-guaranteed coverage, opinions are still highly malleable.

Earlier polling by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that if you present voters with the argument that single-payer would give the federal government too much control over health care, support drops by more than 20 percent. More recent polling from the foundation shows another troubling sign.

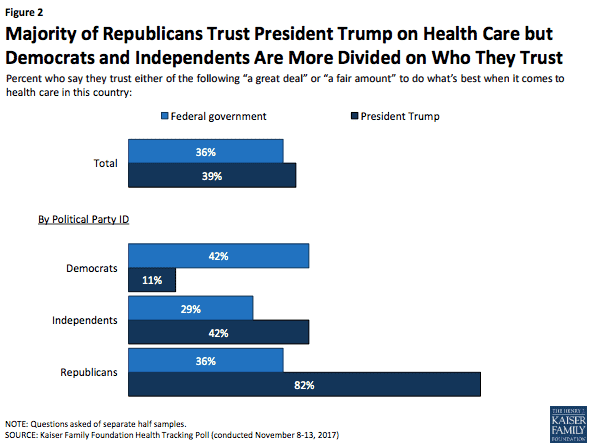

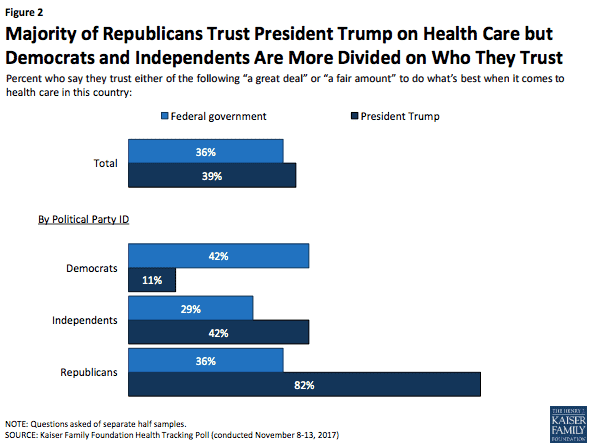

Only 36 percent of Americans said they trusted the federal government to do what’s best for health care, according to Kaiser’s November tracking poll. The figure was about the same for President Trump (39 percent). There were some predictable partisan divergences: Only 11 percent of Democrats, for example, said they trusted Trump.

More disconcerting for the Democratic politicians who want to expand the government’s role in health care: Less than half of Democrats, 42 percent, said they trusted the federal government generally to do what’s best.

This aligned with what we found in our focus groups in Bethesda, Maryland. Perry, who partnered with Vox to run the focus groups, chose these Clinton voters in part because they might be a little more ambivalent about single-payer health care. They have insurance through their jobs. They make a good income. They are some of the folks you might expect to be most apprehensive about totally disrupting the health care system as it exists today.

But they did all believe health care was a right. They were disgusted that so many people in America can’t afford care, and they believe significant change is needed. They had some of the expected concerns about single-payer, like a lack of choices and higher taxes, the concerns that Trump leaned into in his tweet about the UK.

The biggest hurdle, however, seemed to be this decaying trust in the government to oversee the kind of universal health care program that Medicare-for-all would be.

Trump has sown doubt among Democrats about the government’s role

This year, these voters have watched Republicans come within a single Senate vote of repealing the ACA almost entirely. They have seen Trump slash advertising for open enrollment and issue executive orders designed to erode the law further. The Republican tax bill repealed the ACA’s individual mandate, unraveling one of the pillars of the law’s structure.

Bruce, a 61-year-old who works in human resources, summed it up nicely as we discussed who would be responsible for deciding what care should be covered in a government-run system:

“That’s where I have concern,” Rick said, agreeing. “I’m not concerned with the general day-to-day people who are in these positions who are doing the work because they believe in doing the research because they believe in helping people. I’m concerned when politics comes into it.”

Somebody floated the idea of seven-year terms for a board to run a Medicare-for-all program.

The instability personified in Trump clearly weighed on them. Last year, congressional Republicans tried repeatedly and for months to roll back the Affordable Care Act; now the administration is issuing new regulations and accepting state Medicaid waivers to unravel it through different means.

“Do we really even know what the Affordable Care Act is?” Angela, a 47-year-old teacher, told us. “No one has looked at it as individuals to say, ‘Okay, this is what it really says.’ It has just become a political thing of it. If you don’t like this party, and you attack this.”

“Congress can’t get together and do anything right now,” she said. “So no, I don’t trust them to say, ‘This is the health care you should have.’”

These voters were keyed into the idea that a new administration could be responsible for this single-payer health care program every four years — or every eight years at the most — and given the turnover from President Obama to Trump, that gives them pause.

Or as Bruce put it simply: “Four years from now you’ll have the new president; you’re going to scrap everything that this one did and you could start from scratch.”

“If the government’s running that and then suddenly you get a super-conservative Congress and presidency or whatever, do we suddenly change all the coverage?” Elizabeth said. “Or is there coverage that’s guaranteed?”

In a sense, these people might just be catching up with the rest of America. Faith in the presidency, Congress, the Supreme Court, even the military (for the very first time) had dropped below 50 percent by 2016, according to Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. These voters — making more than $100,000 a year, living in one of the most expensive metro areas in the country — may have been among the last Americans to be inoculated from that unwinding.

Democratic voters do want a more expansive Medicare program

The Democratic voters we talked to were also more positive about Medicare buy-in proposals, an alternative to single-payer that Sens. Tim Kaine (D-VA) and Michael Bennet (D-CO) and others have proposed.

Under a Medicare buy-in, a government-run plan would be available on the Obamacare marketplaces for people to purchase. It’s a new spin on a public option, one that would allow more people to join Medicare without completely overhauling the health care system. (For our focus group, we asked the participants to assume that the Medicare buy-in would stand on its own, rather than serve as a runway to full Medicare-for-all.)

These voters liked the idea that people would still have options to choose from. They liked that it wouldn’t disrupt their own health insurance, which they were happy with.

“I think it’s good to have an option,” Archana, a 63-year-old former State Department employee, said, “and good to have an option which will lower the price.”

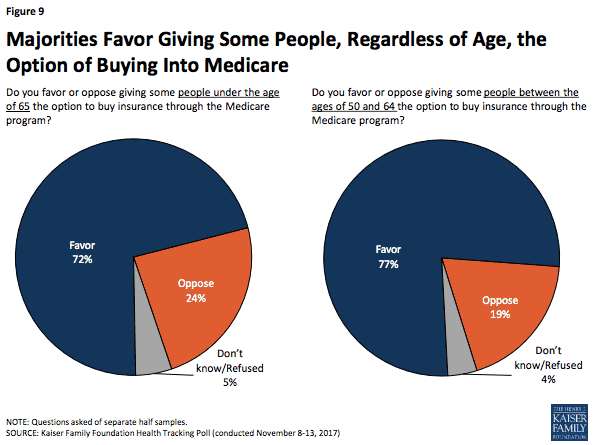

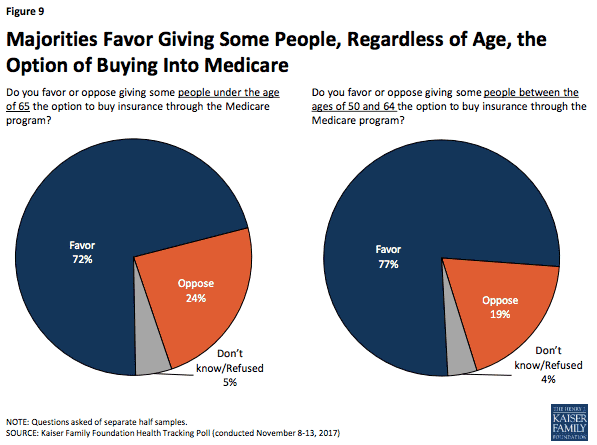

That tracks with what the Kaiser Family Foundation found in its November polling: Roughly three-quarters of Americans support allowing more people, either everyone or people over 50, to buy into the Medicare program. Support exceeded 80 percent among Democrats.

So Democratic voters are receptive to an expanded Medicare program, one available on the Obamacare marketplaces (as were some of the Trump voters we met a couple of days later in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania).

They could be receptive to a single-payer program, but they will need some more convincing. Trump’s election has started to unravel their belief that the government could actually run such a system.

They could be persuaded. But they say they aren’t hearing about the plan from the Democrats right now. Nobody had heard of a Medicare buy-in program before we told them what it was. A few were familiar with Medicare-for-all, and associated it with Bernie Sanders, but not most of them.

“I think that it’s been really poorly articulated. I totally agree that I don’t know what the Democrats think. It’s not been articulated,” Ken said. “Either because they can’t articulate it or they don’t want to.”

Sourse: vox.com