Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Before production began on the 1984 film “Beat Street,” a semi-fictional drama about the early days of hip-hop and breaking in the South Bronx, a researcher on the production team visited Ricky Flores at his apartment. Flores was a young Puerto Rican photographer from the neighborhood who had been taking pictures of the teens he grew up with—his crew. The “Beat Street” team wanted to look at Flores’s photographs to make sure they got the look and feel of the culture right. “This is not a film about break dancing,” Harry Belafonte, who served as a producer, said. “It’s about the people who make up the hip-hop culture.”

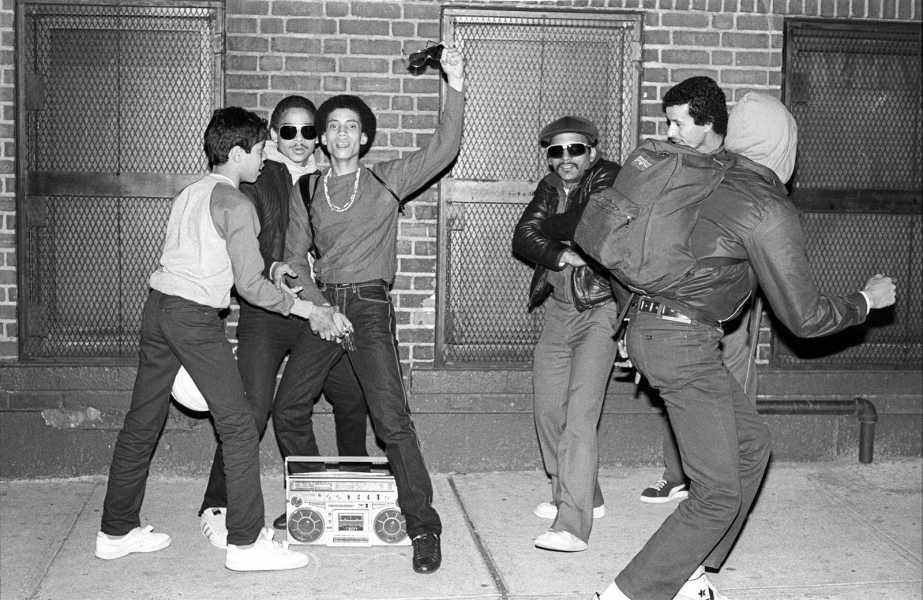

Having fun on the block.

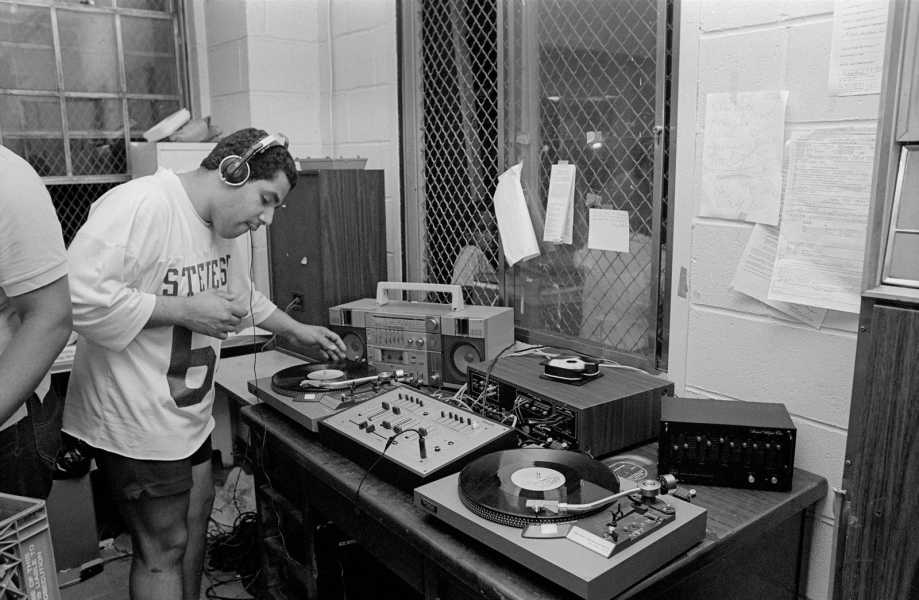

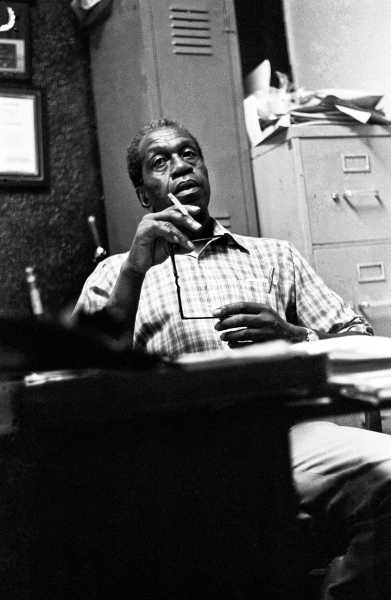

DJ Willie Dynamite.

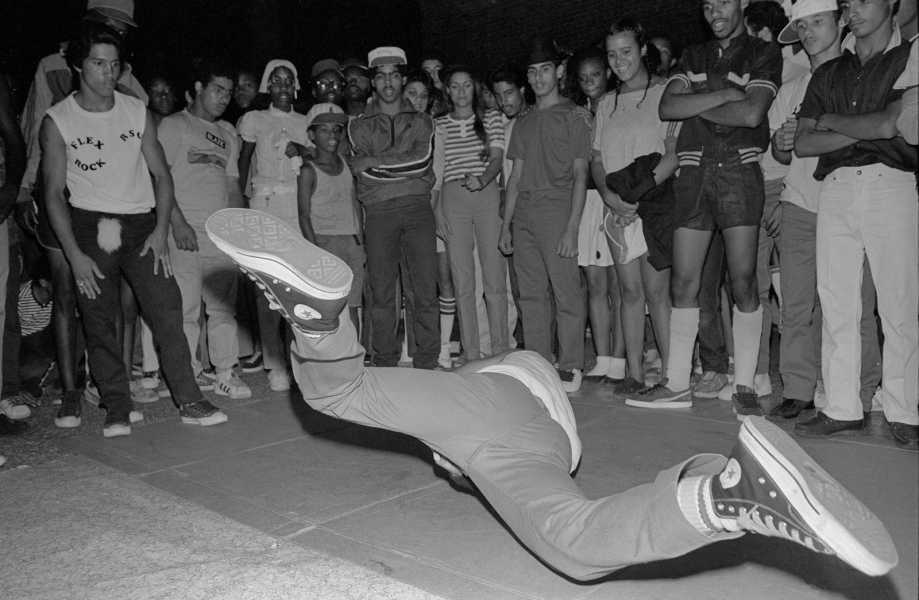

Breaking battles at 52 Park.

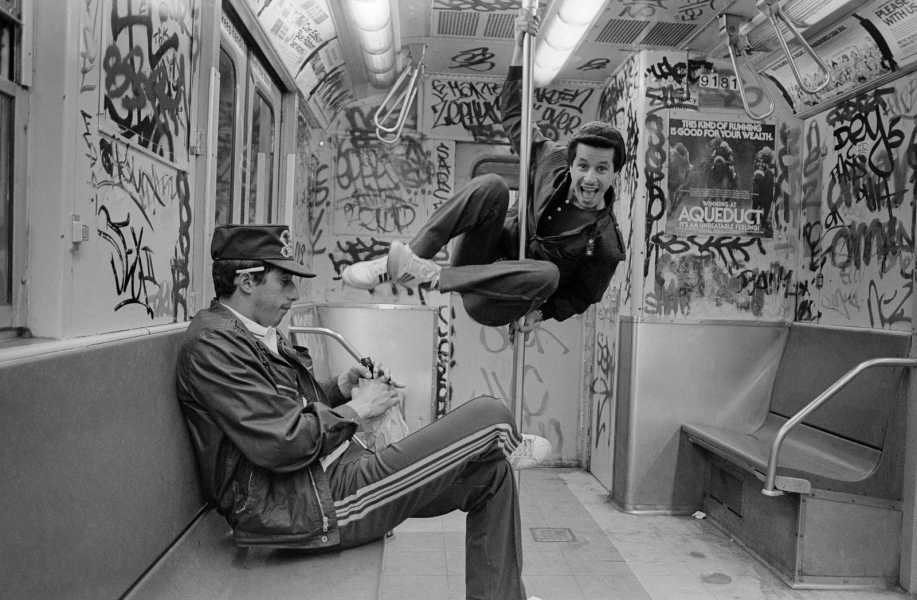

Boogie and Carlos on the train.

“The bastards,” Flores said, when I spoke with him recently. “They used my shit as source material, and all they gave me was a free subscription to The New Republic.” They gave him no credit, and little compensation. But Flores kept capturing images of his neighborhood, and beyond. He photographed the protests in Washington Heights in response to the murder, by police, of a twenty-two-year-old Dominican immigrant named Jose (Kiko) Garcia, just a couple of months after the Rodney King riots in Los Angeles. In the days after 9/11, Flores took an iconic photograph of firefighters hoisting an American flag above the rubble of the Twin Towers. In subsequent years, he took pictures of a Mexican rodeo in Yonkers, Ecuadorian migrants who settled in Ossining, and Puerto Rico after the devastation of Hurricane Maria. In 2011, Representative Charles Rangel honored Flores and other “Puerto Rican Photographers of New York” on the floor of the House of Representatives, and he has received citations from New York’s City Council and the State Assembly for his “service to their community.” Now his early photos, the ones the “Beat Street” researchers consulted, are collected in a new book, “The South Bronx Family Album,” published by Culture Crush Editions.

Summertime scenes from the block.

A summertime game of dominoes.

Josephine and Vinnie looking out the window.

Flores’s parents came to New York in the nineteen-fifties, a period known in Puerto Rican American history as the “great migration,” when some fifty thousand people from the island arrived in the city each year. His father was a merchant seaman, and his mother was a garment worker. Flores was born in 1961. His father died of asthma just four years later. His family was “dirt poor” after his father’s death, Flores told me, and he and his mom moved from the north Bronx to the heart of the south Bronx to be closer to her family. Yet his dad had been able to leave him a small inheritance, which he could access when he turned eighteen. With it, he bought a Pentax K1000, largely, he recounted, because of the influence of a friend named Joey Rios, who taught Flores martial arts and engaged him in “long intellectual discourses about what was happening in the world.” Joey also had a camera. Flores remembers “just holding it, and the feel of it was instantaneous. I loved it.”

The community leader Bill Rainey.

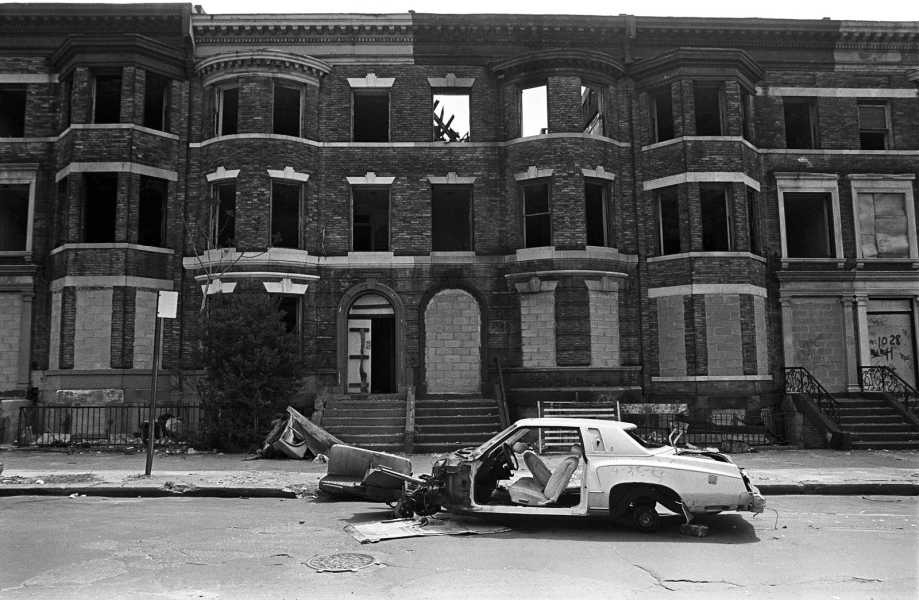

A fire in the Bronx.

After a fire.

Flores went to libraries and bookstores, where he bought, borrowed, or stole everything he could to teach himself about photography. “Remember, I was a poor kid,” he said. “If you understand that part, everything else kind of makes sense.” The first darkroom he had access to was in the basement of the Police Athletic League’s Lynch Community Center, at 156th Street and Beck Street. Nobody had used it in a long time. William (Bill) Rainey, an African American veteran of the Second World War, after whom a park in the Bronx is named, was the longtime director of the center. He dropped a legal pad in front of Flores and told him to write down everything he would need to get the darkroom up and running, and then he bought the supplies. Flores didn’t know how to print photographs, but he learned through trial and error. One night, Flores got locked inside the building. He stayed overnight, because he worried that, if he broke out and the door remained unlocked, someone might take the equipment.

Playing congas on the corner.

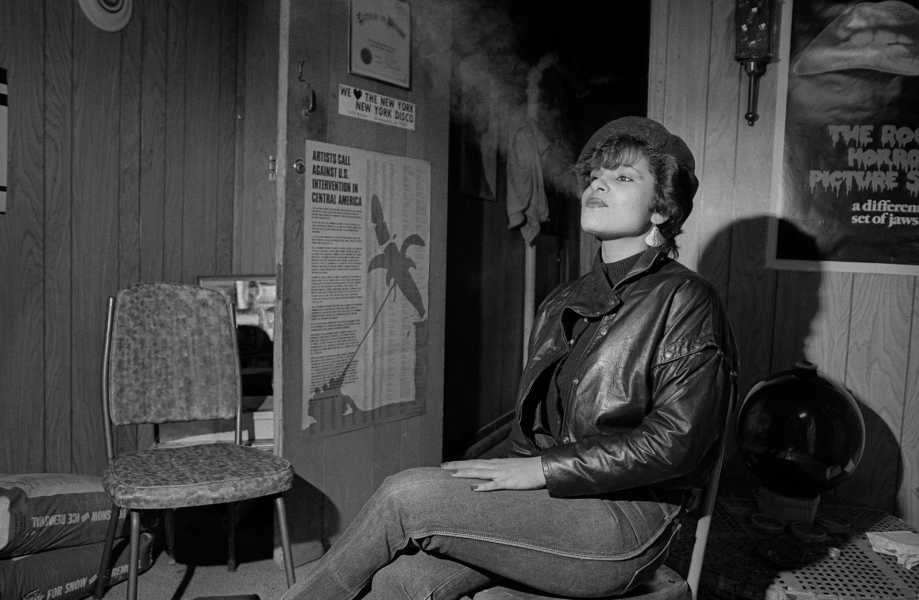

Scenes from “La Cueva.”

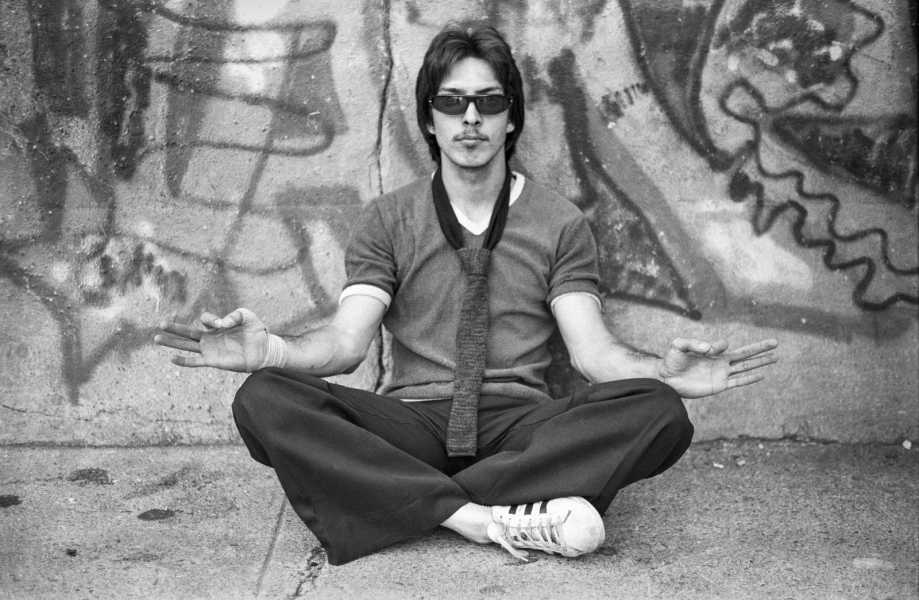

Joey in a meditation pose.

Many of the photos he took during those early years appear in “The South Bronx Family Album.” In addition to Joey, who is pictured sitting cross-legged in a Buddha-like pose, wearing sunglasses and a loose-fitting knit tie, there was Boogie (the jokester and the d.j. in his crew); Eddie (the brawler, whom they called Knuckles because “he had these boulders at the end of his hands that nobody wanted to get hit by”); someone called Pimp; and Watu, Carlos, Santo, Louis, Pete, and Guillermo. There were also the girls they hung out with: Audrina, Maritza, Yolanda, Elaine, Diana, Venus, and others. These are the “family” members at the center of his album. Flores captures them sitting on stoops smoking cigarettes, playing basketball, roughhousing, playing in water gushing from hydrants, sunbathing at Orchard Beach, congregating in front of bodegas, listening to their boom boxes, playing instruments, dancing in the streets, dancing in social clubs. He also took pictures of others in his neighborhood who were outside his circle—girls going to church, people marching and dancing in the Bronx Puerto Rican Day Parade, passengers on graffitied subway trains, kids in front of bodegas, Puerto Rican nationalists who had fired on Congress in the nineteen-fifties, and firefighters dousing buildings engulfed in flames. All of these scenes captured the culture in which hip-hop and breaking were born.

The Puerto Rican Day Parade.

Summertime salsa at Orchard Beach.

Flores’s community was only one among many in the South Bronx at the time. He told me that he had never even heard of Clive Campbell, better known as DJ Kool Herc, credited as one of the founders of hip-hop. He learned about Herc only in 2008, when he was talking with Joe Conzo, Jr., another photographer on the scene, who had taken pictures of Herc, Tony Tone, the Almighty Kay Gee, and many others. For Flores, though, hip-hop and breaking had multiple origins. The Black and Latino residents of the South Bronx did it all together, all at once. That much “Beat Street” got right: its main characters are Black, Latino, and Black and Latino. But some of the early figures are better remembered than others. Describing the musical inspiration for “Hamilton,” Lin-Manuel Miranda recalled watching “Beat Street” with his sisters, and listening to m.c.s like the Fat Boys and Eric B. & Rakim. Flores tells other origin stories, including one about a dance move called the Dale Webo (pronounced “dah-leh weh-boh”). The first person he saw do it was a guy called Loco. There’s a photo of him “dropping his drawers and grabbing his crotch,” a dance move that morphed into something used to diss competitors, Flores said. “Is he the progenitor of that particular move? I don’t know. There’s no way for me to tell. All I know is I never saw it before.” Twenty years later, he saw a friend teaching the Dale Webo in an online class on dance. For better or worse, it was, by then, a staple of breaking. Flores remembers asking his friend, “You’re teaching that? Are you insane?”

Vinnie and his mother, Elaine, on the subway to Orchard Beach.

Sourse: newyorker.com