Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In the short autobiographical vignette “Alien—1965,” the late writer and actress Cookie Mueller offers what might be a perfect snapshot of teen-age girlhood. “I was always leaving,” she writes. “Every time I left I had a different hair color and I would be standing on the porch saying goodbye to the older couple in the living room.” Mueller’s parents—with whom she had nothing in common except “a few inherited chromosomes, the identical last name, and the same bathroom”—would scream and protest, but Mueller would ignore them, speeding off to who knows where or for how long in her friends’ cars. And yet, her relief at being away from home was always short-lived. “At this point it would always dawn on me that there was another problem,” she continues. “Not only was I alien to my parents, but I was an alien to my friends.”

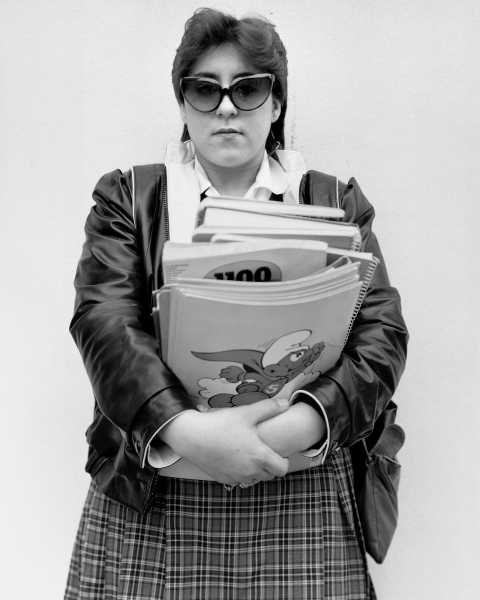

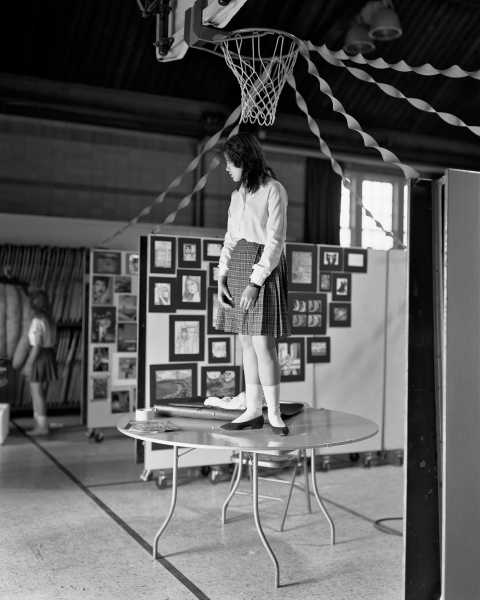

Not every youth is as tumultuous and itinerant as Mueller’s, whose frequent leave-takings had her living hard from Baltimore to San Francisco, Orlando to Provincetown. But the sense of estrangement she describes—from one’s environment, one’s family, one’s peers—is, I’d argue, a reliable marker of even the most conventional teen-girl experience. It’s the kind of alienation we can identify in the black-and-white photographs made in the mid-eighties by Andrea Modica, and now collected in “Catholic Girl,” a handsome, recently published volume from L’Artiere.

Modica, a professor at Drexel University in Philadelphia, whose photography career has spanned forty years, was a young graduate student at Yale’s School of Art when she embarked on the project that would become “Catholic Girl.” On an unseasonably snowy day in the spring of 1984, she decided to take the subway to visit an old art teacher at her alma mater, an all-girls Catholic high school in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. She was lugging with her, as she almost always was, her large-format eight-by-ten camera, and, when she arrived at the school, she decided to ask some students if she could take their portraits.

“There are people who know instinctively how to take a picture, and I wasn’t one of those people,” Modica told me, when we spoke over the phone recently. “And so I was always taking pictures very diligently, always learning.” However, she seemed to instinctively sense that photographing these schoolgirls, who were only a handful of years younger than her, would make for a fruitful experience. “I recognized something there that I had to deal with about my time in high school—something both horrible and wonderful,” she said. “And I had the privilege of dissecting it through these pictures.”

The first photograph Modica took at the school was of two girls: one a tween, the other perhaps sixteen or seventeen. In the picture, the girls balefully face the camera as they pose against a building’s wall; the path below them is lined with the dregs of the recent snow. The younger of the two wears a kilted dress, black knee socks, and a plain headband—a textbook illustration of a Catholic schoolgirl. The teen, however, has already begun to disentangle herself from the expectations of her environment. With her hair sprayed into a nineteen-eighties pouf, long earrings, and unevenly scrunched socks tucked into ballet flats, she is almost a woman, negotiating her emerging role. Standing side by side, the two students read as two adjacent points on a girlhood timeline. (Could the next point be the unseen young photographer taking the picture—a onetime Catholic schoolgirl herself?)

Modica continued to take pictures at the Bay Ridge school, and at a few Catholic schools in New Haven. She often photographed the students she encountered in pairs. Like Diane Arbus’s well-known picture from 1967, in which two seven-year-old identical twins, dressed in dark dresses, face the camera head on, Modica’s photographs of pairs tease out the tension between individuality and sameness. The girls in her pictures are not twins, but they are twin-like: sharing hair styles, uniforms, accessories. And yet, one can also feel each girl’s pulling away from the other. In one image, we see two girls, their dark hair similarly feathered, wearing Members Only-style jackets and plaid skirts. With their hands buried deep in their pockets, they stand with one’s bare, bended knee very nearly touching the other’s. It is as if they are drawn to each other by a magnetic force, whose power somehow stops short, halted by each girl’s own impenetrable force field. In another image, two students wearing matching winter coats, skirts, and black tights are only distinguishable by their hair styles—one short, one long—and by their shoes, one pair of which has white laces. The picture is reminiscent of a “Spot the difference” puzzle, leading us to ask ourselves not just what makes a person but what makes a girl.

When I spoke to Modica, she emphasized the importance of the eight-by-ten camera to her practice. It’s a bulky, unwieldy implement, but using it allows for incredibly precise, luminous results. (Modica also develops her own film and produces her own platinum prints.) Since each shot requires a lengthy setup time, the camera also gives its subjects the sense that they are sitting for an official portrait. This was certainly the case with the “Catholic Girl” series. “It was such a slow and collaborative process,” Modica told me. “And the girls were so generous.” Looking at the pictures, we can see this gravity marking the students’ faces, as if realizing that their encounter with Modica was giving them a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be seen and understood, no matter how alien they might have felt, even to their own selves.

Sourse: newyorker.com