Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

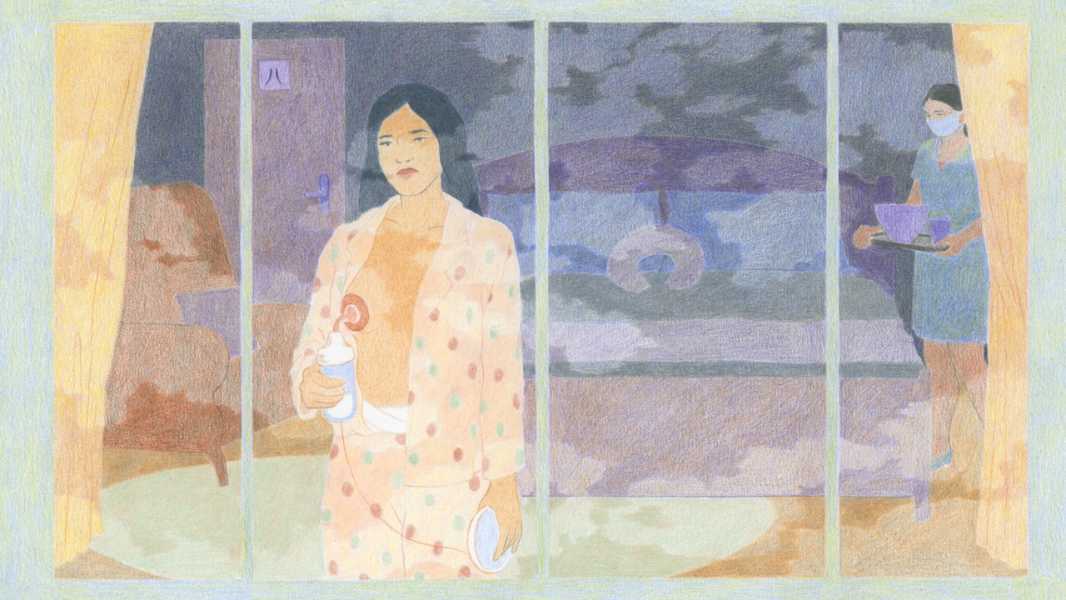

A week after I gave birth to my son, I lay face up on a heated massage table so that another woman could milk me. Spa music twinkled in the background as she squeezed a few drops into a glass bottle. I was trying not to feel embarrassed for producing so little—was my emergency C-section to blame?—when the awkward small talk began.

“How long is your stay in Taiwan?” she asked me. Her bobbed hair bounced a little as her bare hands pressed down on my boobs.

“I live here.”

“You have an accent.”

“I was born and raised in America, but I’m also Taiwanese.”

I stared at a baby-blue flower motif on the wall, which reminded me of areolae. Relax, she told me. Maybe I should try sleeping through the night. My baby was mostly formula-fed anyway, she said, as though I needed reminding of my low supply. “Getting up every two hours to pump is exhausting. You’re just tied to the baby.”

The massage therapist’s advice seemed like the opposite of what I’ve been taught as an American. In the U.S., the first month of motherhood is often seen as painful and difficult by design. After my friend Laura gave birth, in Los Angeles, her back hurt so much that she had to go to physical therapy. “I had coffee ice cream for breakfast every morning as a survival mechanism,” she texted me. My college roommate, Emily, told me that her newborn son clamped onto her breasts for a week straight. “For better or worse, I’ve built up calluses,” she said.

I, on the other hand, was lounging at a luxury postpartum hotel in Taipei, leaving much of the hard work to an army of nurses. I could sleep in a fluffy queen bed, wake up to a floor-to-ceiling view of the city, and eat a hot breakfast of rice porridge, poached greens, and herbal tea. The experience was so indulgent that it felt wrong.

At the end of the milking session, the massage therapist handed me the result: less than a teaspoon of custardy-yellow breast milk. She didn’t want me to feel bad about it, though. “The postpartum period is a time to rebalance your qi,” she said. “You have time here.”

In Taiwan, an old folk saying sums up this attitude: “During pregnancy, nurture the baby. After pregnancy, nurture your body.” Giving birth is believed to disturb the body’s equilibrium, so new mothers traditionally engage in zuo yue zi, or thirty to forty days of rest at home, pampered by family. Literally, the phrase means “sitting the month,” but it is often translated as postpartum confinement, away from the stress and sickness and cold of the outside world. My mom always emphasized the role of food: some dishes, like pork trotters with peanuts or ginger chicken drenched in sesame oil, are said to repair the uterus.

These days, Taiwan tends to leave the postpartum month to professionals. New mothers can stay in one of approximately two hundred and eighty specialized hotels, where they will receive food, round-the-clock child care, doctor visits, and miscellaneous perks such as yoga classes and milk pumping. According to Gary Lee, the founder of MamiGuide, a Web site that books postpartum-hotel stays, they cost an average of two hundred and twenty U.S. dollars per night. For Americans, this can seem like an unbelievable deal. But here, where the average salary is slightly more than twenty-two thousand U.S. dollars, a monthlong stay can consume between twenty to thirty per cent of one’s annual income. Still, according to Lee, sixty-five per cent of postpartum parents check into one of these hotels, even if that means saving up for years. “It’s like buying a diamond ring,” Lee told me over the phone. Similar accommodations are available in China and South Korea.

Milk in hand, I exited the spa, shuffled down the hallway, and pressed a button in the wall. A door slid open, revealing a small, closet-like room decorated with baby photos and thank-you letters. A masked nurse in green scrubs greeted me brightly: “Hello, Mommy!” I gave her the milk along with my room number, eight. My son was somewhere in a nursery behind her; so were dozens of other wailing newborns.

As I handed over my breast milk, it hit me that I was outsourcing a cherished ritual, breast-feeding my newborn, to strangers. But the hotel existed so that I could focus on my needs, I told myself. I went back to my room, plopped onto a cerulean-colored velvet couch, and opened an app on my phone. A live video of my snoozing baby, his blue pacifier hanging limply out of his mouth, filled the screen. A sticker on his swaddle showed the number eight. We would have plenty of time together later, I thought, trying to suppress a sudden wave of guilt. Right now, it was time for my nap.

When I was born, three decades ago, in Los Angeles, my grandmother flew over from Taiwan with a suitcase full of Chinese herbs, intending to oversee my mother’s zuo yue zi. She quickly tired of babysitting, however. “She just wanted to go to San Diego and see our relatives,” my mother told me. In the weeks after my birth, my mom remembers developing chronic fatigue. In her view, the postpartum period sets a precedent for future health. I assumed, therefore, that she would want to supervise my zuo yue zi. But when I asked her at the start of my pregnancy, over dinner in Taipei, she only laughed.

“Do you want me to die early?” she said. “Newborns are exhausting.”

And so I started touring Taipei’s postpartum hotels. I learned that, instead of enforcing taboos associated with a traditional postpartum month (don’t wash your hair, avoid ice water), they offered amenities with a similar vibe, such as heaters, warm foot baths, and hot herbal tea. But there was something condescending about the hotels. Staff members kept calling me Mommy. Although dads and employees could come and go freely, moms had to check in and out. Visitors weren’t allowed in hotel rooms, and could see newborns only through a glass window. We weren’t allowed to take our own babies outside unless they had a doctor’s appointment.

During one of my tours, I asked a nurse if I could go for daily walks. “Yes,” she replied, and then hesitated. “Most people don’t, though. You’re supposed to rest.”

Eventually I settled on Whole Love, which was built in my neighborhood a few years ago. Whole Love, which has twenty-three rooms, describes itself as a care center, while moms tend to call it a hotel. Although it didn’t have a partnership with a Michelin-recommended restaurant, like some postpartum hotels, my room would have its own massage chair, bottle sterilizer, and breast pumps. I could schedule a manicure or learn to make soap out of breast milk (not that I would have much to spare). I chose Whole Love mostly because it was close to home.

My husband worried that I was signing up for a kind of quarantine center for mothers. “Are you sure about this?” he asked. Wouldn’t I be more comfortable in our apartment, where he could cook and I could go outside?

I was grateful for the offer, but it struck me as naïve. My husband’s excellent cooking had never included bone broths infused with Chinese medicine. My family didn’t want to look after us, and his was thousands of miles away. We lived in a rare place where postpartum care was a norm; some of our friends had cried when their hotel stays came to an end. Shouldn’t we jump at this opportunity?

When my delivery date arrived, my doctors tried and failed to induce me. Two days later, they resorted to an emergency C-section. Afterward, I felt like a deflated sack; I could barely lift my head. It seemed unfathomable that in the U.S., where caregivers joke about “drive-through deliveries,” the average new mother who has had a C-section stays in a hospital for only two to four days. I stayed for five. Then my parents drove us to the hotel.

As our newborn snored in his car seat, my body tingled with anxiety. What if he woke up and started crying? What if we got stuck in traffic and he soiled his diapers? I had spent most of the time in the hospital bedridden, and my husband had spent most of that time caring for me. Our beloved child was still an enigma to us.

“Aren’t you glad we’re going to the hotel now?” I asked my husband.

He nodded. “We’ll use this opportunity to learn from the nurses.”

We rode an elevator to the fifth floor and waited in a dark lobby. I felt as if I were at a zoo: on the other side of a glass wall, we could see a brightly lit nursery, where nurses matter-of-factly lifted and lowered babies, as though they were dolls. Then a nurse came into the lobby and plucked our baby out of his stroller. For the next thirty days, the hotel would monitor his needs and control his movements. I only needed to look after him when I wanted to.

In Room 8, a collection of dainty white bowls waited on a platter: clam soup, steamed fish, crunchy okra with beef slices, bright greens sprinkled with goji berries. I felt a surge of optimism. I was going to treat the hotel like school, and graduate into the best mother I could be.

The food was meant for me, so my husband left to find some lunch. A receptionist handed me onboarding materials, bath-product samples, and information about a service that preserves umbilical cords. Next, a nurse showed me how to label breast milk. Once a day, she would take my temperature and blood pressure; twice a week, she would help me change my C-section bandage.

The telephone by the bed rang. My baby was hungry. Did I want to feed him, or did I prefer to rest? I chose the former, as though I were ordering room service.

A couple of minutes later, he was wheeled in on a cart, which contained a perfectly warmed bottle of formula and a drawer of fresh diapers. Newly washed, with his hair neatly parted, he looked like a present for me. The nurse told me to sit on the sofa and gently pressed my baby into my arms. “Make sure to burp him frequently,” she said. If I needed any help, I could call the nursing station. Then she closed the door, and for the first time in my life I was alone with my son.

My baby came with detailed instructions. I was to feed him every four hours, fill out a chart with how much he ate and when, and mark any diaper changes. This sounded easy enough; I imagined myself lounging in bed, sipping tea as the baby cooed. But with me he often cried until he was purple. He had spent the past nine months curled up peacefully inside of me, with no complications. Now that he was out in the world, why couldn’t I soothe him?

Many times, a nurse took my son from my arms and bounced him to peace. Then, when he landed in my arms again, he would erupt in anger. She would try to reassure me, but eventually she had to return to the nursery. “You can just wheel him back to us if you need a break,” she would say. I was overwhelmed, and I started sending him back after every feeding.

For weeks, I spent no more than four hours at a time with my son. I felt terrible about it—I seemed to be trading intimacy for tranquillity—but I told myself that he appeared happier with the nurses. Maybe the instinct to suffer through discomfort was too American. I kept thinking back to the massage therapist who’d milked me. “You have time here,” she had said.

The first time my son pooped at the hotel, I called a nurse over in panic. At the hospital, my husband had handled diaper changes.

“Do you know how to change a diaper?” she asked, without judgment. When I nodded hesitantly, she demonstrated, propping his body on her left arm while gripping his thigh like a drumstick. At the sink, she peeled off his diaper and used the faucet as a bidet, before cleaning him with wipes. My baby was delighted.

“Can’t we just use wet wipes?” I asked.

He was less likely to develop diaper rash this way, she said gently.

Some of the activities were genuinely sweet. During a baby-swimming session, my husband and I clapped in encouragement as we watched our son, ensconced in an inflatable ring and surrounded by rubber duckies, confidently kick around in a full-sized bathtub.

On another evening, a photographer and his assistant came into my room. After setting up some backdrops on my bed, the assistant stared my son in the eyes and began to hum, low and melodic. Immediately, the baby fell into a trance. They managed to dress him as a newspaper boy, as a bunny rabbit, and in beach clothes. When they wrapped him in a green pear costume, he fell asleep.

As adorable as the photo session was, it made me feel useless. I was learning a few tricks from the staff, but they did everything for me, and they were better at it. About three weeks in, I began to feel claustrophobic. In the long, dark hallway between rooms, my fellow-moms didn’t make eye contact. Occasionally, I overheard bits of people’s lives. “Don’t cry, don’t cry,” one mother pleaded in the room next door.

Another time, I was holding my baby in my room when I heard a man’s angry voice in the hall. “This place is like a jail,” he shouted. “My wife is in her room, crying. I will sue you!”

My son glanced up at me, puzzled by the commotion. “Sh-h-h,” I told him. Through the door, I could hear stomping feet and the low voices of staff.

Although the hotel advertised itself as a modern and flexible take on postpartum traditions, it wasn’t wrong to call it a place of confinement. I couldn’t have my girlfriends or parents in my room, or take my son out for a stroll. Everyone had a uniform: mothers wore white pajamas with pink and green circles; nurses, who were exclusively women, wore green scrubs; and babies wore off-white kimonos. Only dads wore street clothes and had no official role—a reflection of a traditional society in which mothers are expected to be married to fathers and tend to be the primary caregivers. The few times I did step out—for a snack, a quick coffee with a friend, and a much-needed date with my husband—the nurses asked me where I was going. I always felt ashamed. “Errands,” I’d lie.

During my last week, I finally made a friend. Mariah, a Taiwanese Canadian woman, had just given birth to her second child, a baby boy. One afternoon, after our morning feedings, we grabbed bubble tea and sat on the roof. The nurses literally gasped when they saw us together.

“When I had my first kid, I was just grunting,” Mariah told me. Because she hadn’t trusted her live-in nanny, she’d done night shifts by herself, and grew so tired that she could barely speak. So, the second time that she was pregnant, she immediately put down a deposit for a hotel.

I confided that I was having a difficult time being alone with my son. My American friends probably envied me, but I was starting to wish I could trade places with them; for all their sleepless nights, they seemed to have bonded with their newborns immediately. With a week left in my stay, I felt about the same as I had in the car: anxious, inadequate, confused.

The point of the postpartum period was not to learn skills, Mariah reminded me, but to recover physically and mentally from the rigors of pregnancy. On her phone, she toggled through parenting apps that she wanted me to try.

“How long do you have your baby with you in your room?” I asked.

“Eight in the morning to eleven at night.”

The shock must have shown on my face. “The point is that I can sleep through the night,” she said.

“How do you eat?”

“Quickly.”

Paradoxically, she gave me a guilty look. “My friends say I should rest more,” she said. I was feeling bad for spending too little time with my son; she was feeling bad for spending too much. Our desires to take care of our sons and ourselves seemed mutually exclusive.

On the day we checked out, my baby was given a “diploma” to commemorate his first month of life. But, as a mother, I felt as if I had failed. My first three days at home washed over me like ice water. After thirty days of relative calm, I was bewildered by the total lack of personal time. “It’s like hazing, except you delayed it by a month,” Laura texted me from Los Angeles. The only time I felt relief was when I took a warm shower, which drowned out my newborn’s cries across the hall.

Almost immediately, though, I felt the flood of intimacy I had been craving, followed by a quiet understanding. It was simple: I didn’t know my child because I hadn’t spent enough time with him. He threw tantrums when he was overtired, I discovered. He enjoyed contact naps, his dad’s soft chest, and leaning back against the slope of our thighs. He preferred long walks in his stroller to being swaddled in his bassinet. The hotel had absolved me of responsibility for my son, which created an emotional chasm; its rigid routines had stopped us from learning about him as an individual.

Though I didn’t fully understand it at the time, staying at a postpartum center gave me a chance to catch my breath between transitions, before diving into the marathon of parenthood. I had approached it all wrong. In retrospect, if I wanted to connect with my son right off the bat, I should have kept him with me all day, like Mariah did. Or I should have just enjoyed my month off completely, gone out with wild abandon—nurses be damned—and trusted that I would eventually figure it all out.

Now that my husband and I have both gone back to work, we’ve been trying out a couple of part-time nannies who can watch our son for a few hours a week. Our favorite is a woman named Connie, who showed up for her first day in a surgical mask and pink scrubs. At the end of the session, she texted me a detailed breakdown of how much the baby ate and at what time.

Recently, I walked in on Connie giving my son a massage, by stretching out his arms and rubbing his little feet. He broke into a gummy smile. The scene felt familiar. It turned out that, before she became a private nanny, Connie had worked as a nurse supervisor at a postpartum hotel.

I poured myself a cup of coffee and began to prepare lunch. The days when food arrived at my hotel room on a platter seemed like a hallucination. But the anxiety and the feeling of inadequacy were gone. After many delirious weeks, and many hours of bouncing my crying son to sleep, I felt fully inducted as his mother. This time around, I knew my kid better than the woman who was helping me care for him. And, after lunch, my husband and I were going to take him for a long walk. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com