Xi Jinping is ignoring the country’s biggest economic problems.

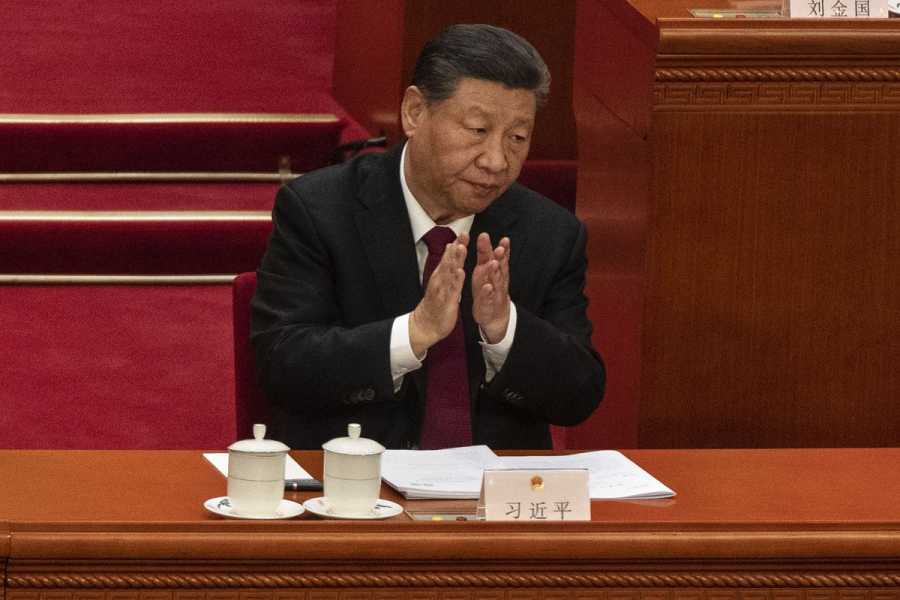

Chinese President Xi Jinping applauds at the opening of the NPC, or National People’s Congress, at the Great Hall of the People on March 5, 2024, in Beijing, China Kevin Frayer/Getty Images Nicole Narea covers politics and society for Vox. She first joined Vox in 2019, and her work has also appeared in Politico, Washington Monthly, and the New Republic.

The Chinese government outlined on Monday its plan to boost the country’s sluggish economic growth, but experts say it fell short of the kind of transformative strategy necessary to fix the country’s debt and consumer confidence crises.

China has enjoyed miraculous economic expansion for the past few decades, solidifying itself as a global power and building an emergent middle class. It achieved that growth through a blend of the governing regime’s Communist principles and a strategic embrace of the free market, creating a novel form of state-guided capitalism that ushered in a new era of economic prosperity.

Recent economic stagnation, however, has called this model into question, forcing the Chinese government to reconsider its approach.

During the annual meeting of the National People’s Congress, Chinese Premier Li Qiang set a new benchmark for economic growth in the next year: a 5 percent increase in its gross domestic product. That target is “relatively ambitious given China’s current economic difficulties,” said Neil Thomas, a fellow on Chinese politics at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis.

But the setting of this ambitious goal isn’t being accompanied by “ambitious reforms to change China’s growth trajectory,” Thomas added. The International Monetary Fund has projected that China will just miss the 5 percent target in 2024, estimating only 4.6 percent in GDP growth, which the IMF then expects to decline to 3.5 percent by 2028.

Though China has relied for years on domestic investment to prop up growth, those investments are no longer sufficient to sustain economic growth at levels the country’s leaders find acceptable. Its economy has become weighed down by spiraling government and commercial debt, a ticking time bomb that finance experts fear could have reverberating effects across the global economy. That, in turn, is fueling economic unease internally, dampening consumer spending as well as hiring and business investment.

Li’s plan aims to combat these problems by shifting more of the Chinese economy’s focus to innovation, manufacturing, and technology. But experts say it likely doesn’t do enough to change the country’s economic trajectory.

“They need to do a lot more to signal a shift in the direction of the country with regard to economic liberalization, winners and losers, China’s relationship with the West,” said Scott Kennedy, senior adviser and trustee chair in Chinese business and economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. ”There was nothing in Li Qiang’s government work report or anything that China has issued in the last few months that show us one iota that China is considering shifting direction.”

China’s economic troubles, briefly explained

China is plagued by a fundamental imbalance in its economy: It has relied disproportionately on government spending and commercial investment to fuel economic development, rather than consumer spending, which would be a sign of more organic and sustainable economic growth.

After the 2008 financial crisis, local governments in China made massive investments in domestic infrastructure and property development, making a bet that property prices would continue increasing. Real estate now accounts for about a quarter of China’s GDP. The country, though, couldn’t support that level of expansion, with a per capita income that is still low compared to other advanced economies. Major property developers such as Evergrande have gone bankrupt. Ghost cities now sit abandoned across the country.

By the end of 2023, China’s accumulated debt had grown to nearly three times its economic output, hitting an all-time high. Some economists have likened the current economic situation in China to Japan’s “lost decade” in the 1990s, a period of deflation and economic stagnation wrought in part by excess debt.

Most developed economies rely on consumer spending to drive economic growth, but that hasn’t been the case in China. There, it only accounted for about 53 percent of GDP in 2022. In the US, consumer spending makes up about 68 percent of GDP.

Making matters worse, the Chinese stock market has performed abysmally since 2022, seeing $2 trillion in losses. China continues to run a trade surplus, but it is struggling to export as many goods as it did previously, as Western countries try to reduce their reliance on the Chinese manufacturing sector given its geopolitical rivalry with the US and Europe.

Economists argue that boosting domestic consumer spending is the best way for the Chinese to dig themselves out of their current economic slump. But getting people to spend more money is tough when many feel as though they’re already experiencing a recession.

And the national government’s latest plans haven’t raised hopes, domestically or internationally.

What’s in China’s new economic plan

The new economic plan announced Monday seeks to increase consumer spending by addressing the country’s demographic challenges, including policies urging people to have more children as China’s aging population presents a structural risk to its long-term economic prospects. The plan also includes measures to remove restrictions on foreign investment in manufacturing and makes a renewed commitment to competing globally in technologies such as quantum computing, big data, and AI.

But while Li promised to “push ahead with transforming the growth model,” his speech was short on specifics about planned changes and time frames. And the premier skipped his annual press conference afterward for the first time in 30 years.

Such a breach of protocol is a “big signal that they just don’t want a dialogue with society and with the rest of the world, and they just want everyone to pay attention and follow along,” Kennedy said.

This flimsy strategy, even amid a growing crisis, reflects Chinese President Xi Jinping’s reluctance to undertake radical structural reforms to the nation’s economy. Nevertheless, that’s what many economists think would be necessary for China to adopt a sustainable model for economic growth, Thomas said.

Those reforms could include overhauling local finances, where most of the country’s debts lie, as well as directing more financing to private firms and removing restrictions on internal migration and land use that have hampered consumer spending. Such an overhaul would also include raising taxes on state-owned enterprises, which currently keep most of their profits, Kennedy said, and instituting property taxes to support local governments.

Strengthening the social safety net could also improve consumer confidence and therefore spending. Victor Shih, director of the 21st Century China Center at the University of California San Diego, noted that Li announced in his speech that subsidies to general medical insurance will increase by $4 per person. But that still isn’t enough to keep up with inflation.

“A lot of economists believe that social welfare provisions should be a lot higher in China, by the thousands of dollars per person. But of course, given the leadership’s priorities, that is unlikely to happen,” Shih said.

Leadership could inject more stimulus later in the year if the economy is falling short of its growth target, but Shih said that for CCP leadership, hitting that target is symbolic of China’s ability to compete with the US. “I think for the top leadership, achieving around 5 percent growth is important because, without that growth rate, it would take a lot longer for China to catch up with the United States in terms of the size of its GDP,” he said.

Chinese leadership’s focus on competing with the US is an extension of geopolitical tensions. The US and China have already been locked for years in a trade war, and China’s efforts to ramp up its manufacturing and innovation sectors are a direct challenge to the West that could lead to more economic brinkmanship.

“Beijing’s focus on turbocharging manufacturing to drive growth will create overcapacity that exacerbates trade tensions between China and the West,” Thomas said. “This could feed into the United States and European countries placing more restrictions on Chinese exports and technologies.”f

US leaders are already anticipating further escalation of this economic standoff. Former President Donald Trump has vowed to vastly increase tariffs on Chinese imports if he is elected again in 2024. President Joe Biden, meanwhile, has signed a law to spur domestic computer chip production and cut China off from related subsidies; he is also eyeing new restrictions on Chinese electric vehicles and other imports in a second term.

Any American retaliation would complicate China’s efforts to course correct at a pivotal moment for its economy.

Sourse: vox.com