In 2011, the photographer Tanyth Berkeley went to Colorado City, Arizona, to meet a woman named Ruth, a member of the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a polygamist sect of Mormonism. As we learn in Berkeley’s new photo book, “The Walking Woman,” Ruth had grown up and married within a branch of the community in Arizona, in which women were instructed to “keep sweet” and submissive, and children, including her many siblings, were beaten into silence. But she had spoken out against the abuse in a documentary film “Banking on Heaven,” from 2005, and appealed to the F.L.D.S. church and local authorities for justice. Instead, she was declared “mentally unfit and institutionalized,” according to the film, and then “exiled from her home and not allowed to see her children.” Berkeley wanted to “see this rebel for myself . . . to congratulate her on her courage and to give her support.”

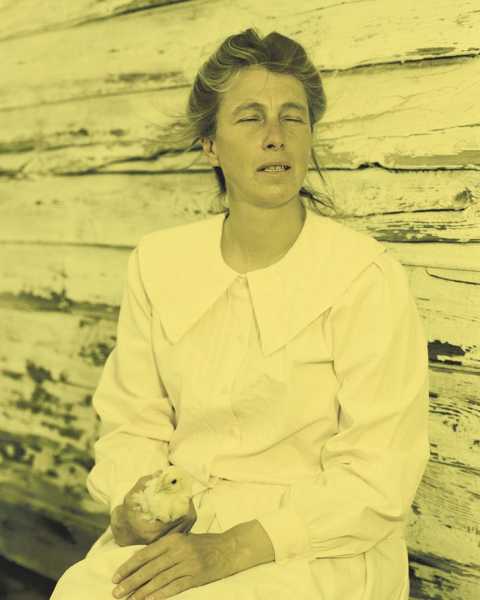

She photographed Ruth against the bleak landscape wearing the pastel and gingham “prairie dresses,” covering the body from neck to ankle, that were prescribed for women in the F.L.D.S., in the tradition of Mormon pioneers. Berkeley describes Ruth as moody and “mercurial”; in the photographs, barefoot, sombre, and withdrawn, her graying hair twisted and pinned back in a severe bun, Ruth embodies the repressive uniformity imposed on women in cults like the Branch Davidians of Waco, or the captive handmaids of Margaret Atwood’s imaginary Gilead.

Berkeley’s encounter with Ruth was the beginning of a long project that expanded to include another female outcast in the Southwest, who has a different history of damage and resilience. “The Walking Woman” connects their experiences visually through their settings—eerily remote towns and trailer parks in Arizona and Utah—against blazing sunlight and garish sunsets in a primitive landscape, which Berkeley describes as a mythic place “where everything appeared untouched . . . where it seemed possible that no one had ever set foot.” She combines her portraits with excerpts from a century-old short story, Mary Austin’s “The Walking Woman,” which was first published in The Atlantic Monthly, in 1907. This allegory of a woman’s lonely journey gives Berkeley’s book its title and theme. Printed on pages opposite the photographs, in white type against a light-blue background, the passages are ethereal, like skywriting or spirit messages, contributing to the feeling of the book as a timeless legend.

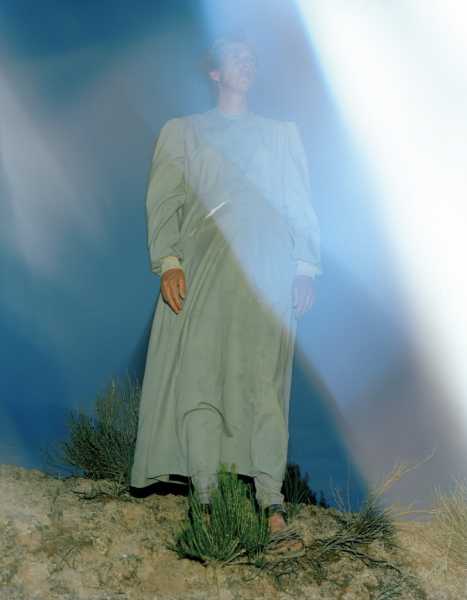

The photographs also evoke images of extremity from painting and history. Ruth lies in dry yellow grass, stretching out like the subject of “Christina’s World,” by Andrew Wyeth. In a black-and-white photograph, she is standing with her back turned, a white column facing a grove of burnt tree trunks resembling the no man’s lands of the First World War. In another, she has her hair down and is waist deep in a weed-rimmed pond, like Ophelia preparing to float downstream. She poses against scratched-up kitchen cabinets in an empty cabin; in a separate photo we see a picture of Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, whom, oddly, she resembles, on a whitewashed wall. She stands—arms spread, head back, eyes closed—against a bleached-out landscape suffused by the light of an overexposed rainbow, in a kind of ecstatic trance, possession, or rapture.

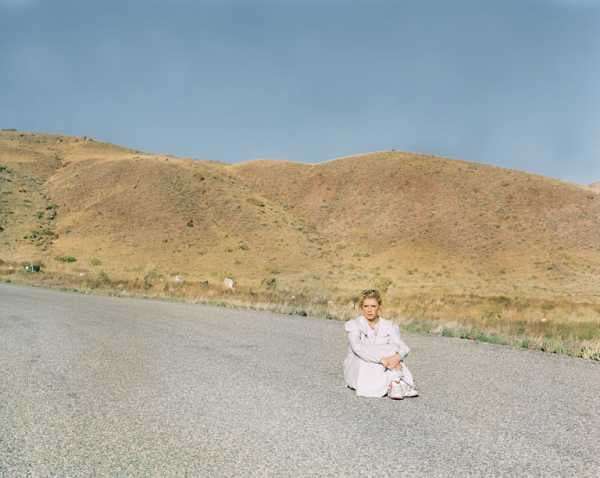

And then Ruth vanishes from Berkeley’s pages. We learn from the book’s notes that she suddenly panicked about their collaboration and ran away, leaving the prairie dresses in the trunk of Berkeley’s car, like a snake shedding her skin. Trying to decide what to do next, Berkeley drove to the Mystic Hot Springs, in Monroe, Utah, seeking the comforting springs she had loved as a child in the West. Camping out there, she woke up at dawn and saw a “hard-looking” young woman walking through the hills. That was Spice, a drug addict who seemed very different from Ruth; but, as Spice and Berkeley exchanged stories, the photographer saw some uncanny similarities between the two women, each of whom had borne five children and endured mental-health issues, poverty, and exile. In the second half of the book, in a kind of mystical rebirth of Ruth, Spice takes over as the subject of Berkeley’s photographs.

Initially scrubbed except for her black eyeliner, her bleached-blond hair pulled back, wearing Ruth’s pink prairie dress and a locket, Spice looks like a “desert rose,” but she couldn’t keep up the pose of chaste innocence for long. A few pages later, she is leaning against a wall smoking, in a strappy, tie-dyed pink party dress and big white sneakers, a tattoo visible above one breast. Inside her grubby trailer she lies on a bare mattress, eyes red-rimmed, her fingernails dirty. In the remaining pictures, Spice looks increasingly desolate and withdrawn. Wearing a blue hoodie, she sorrowfully holds a framed photograph of her smiling little children. In a pink sweatsuit, she stands on the bank of a blood-red polluted pond. In her final photograph, she, too, seems to be vanishing, her features fading into invisibility.

Mary Austin wrote more than thirty books, and was dedicated to exploring and celebrating the landscapes, religions, and Native American art of the Southwest. Her life uncannily foreshadowed the experiences of the women in Berkeley’s photographs. As she wrote in “Woman Alone,” an anonymous essay from 1927, she had been an unloved child, and struggled to conform to rigid expectations of feminine subservience. She labored to raise a severely disabled daughter, and, in 1907, left her unhappy marriage to pursue a successful career as a novelist, moving to Carmel, California, and joining a writers’ colony that included Jack London and Ambrose Bierce. In 1905 she put her daughter in a private institution in Santa Clara, where she died, thirteen years later. Despite her fame, Austin always saw herself as an outsider in an American Western literary culture generally dominated by men. She cultivated a semi-mystic attachment to nature, and especially to the desert, with descriptions that implied a correspondence between the landscape and female sexuality. Toward the end of her life she collaborated with Ansel Adams on a book called “Taos Pueblo,” from 1930.

In “The Walking Woman,” a female narrator tells the story of a mysterious wanderer seen in the hills of the San Joaquin Valley, about whom cowboys and sheepherders give conflicting reports. Is she comely or plain? Crazy or wise? Twisted or straight? Her motives and destination are mysteries, too: “she came and went about our western world on no discoverable errand,” and “whether she had some place of refuge . . . was never learned.” The narrator meets the Walking Woman at a spring, and learns that she had begun by “walking off an illness,” which was caused by years of nursing an invalid and healed by the “large soundness of nature.” She declares that she has known three joyous experiences in her wanderings: loving a man, working with him as an equal partner, and bearing a child. But her baby died, and after its death she became a permanent exile, who has “walked off all sense of society-made values,” and who must wander alone for the rest of her life. In the last lines of the story, however, the narrator sees from her departing footsteps that she has not been crippled or twisted by loneliness and grief: “There in the bare, hot sand the track of her two feet bore evenly and white.”

In Berkeley’s “The Walking Woman,” Ruth reappears in the final picture, on a hill, her back turned, gazing out over the land to the horizon. She is unbeaten, moving on—but to where? Berkeley does not know what became of either of her subjects. Ruth fled the F.L.D.S. community around 2014, planning to change her name and Social Security number and “begin a new life.” Spice, Berkeley writes, served time in jail, and was eventually released, but “her current whereabouts are unknown.” But, together in Berkeley’s book, their narrative threads merge to offer a moving parable of women alone, seeking refuge from addiction, abuse, and confinement in a natural environment that is arid and harsh but offers the promise of healing.

Sourse: newyorker.com