Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

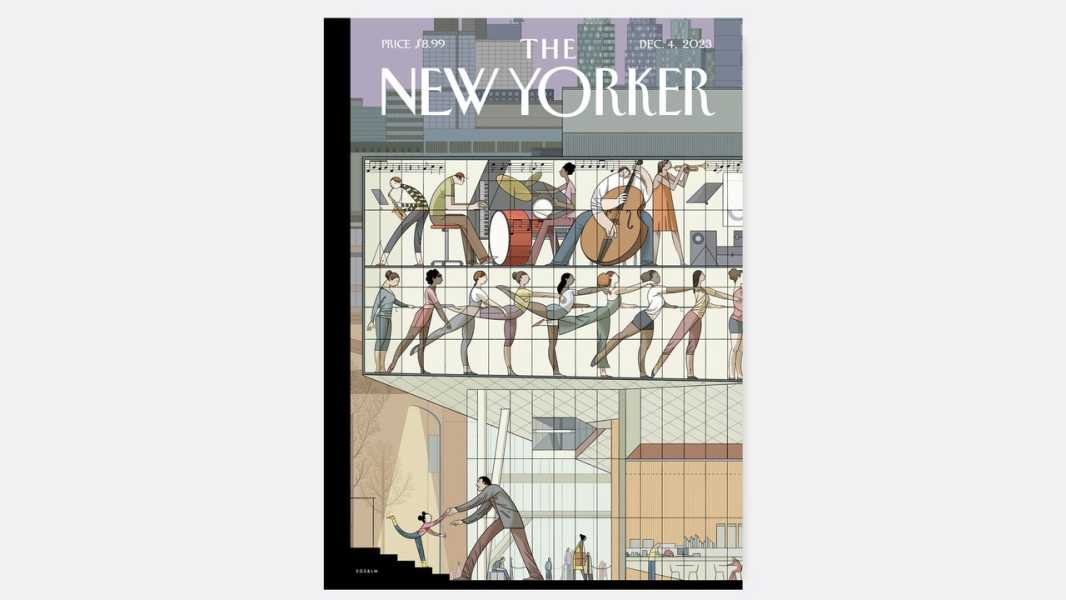

In the city, poetry is everywhere. It’s interwoven with the dense urban fabric of the everyday, present in the mundanities of human coexistence and in the extremes of creative self-exertion. For the cover of the December 4, 2023, issue, Sergio García Sánchez draws an elegant image of the Juilliard School at Lincoln Center, where musicians and dancers train and strive to develop their art. I talked to the artist about the collective and transformative power of movement, words, and images.

Do other mediums, like music or dance, ever influence your work?

Music is a big influence in my creative life. When I draw, I try to create images endowed with rhythm—it is fundamental to my work. When I was young, I made some narrative pieces inspired by the work of Wim Mertens, specifically his musical performance work “Maximizing the Audience.” And dance is the basis of path-drawing, a narrative concept I use when I make experimental comics.

Prestigious schools like Juilliard are known for their rigor. Do you think competition and pressure to excel are helpful in propelling an artist’s development forward?

Above all, I believe in the pressures you put on yourself as an artist—they are crucial. When I talk to my students, I emphasize that the artist is the one who must impose the constraints on himself when creating. I don’t believe much in competition with the work of others; we compete with ourselves.

You recently have completed some graphic novels made in partnership with other authors. Do such projects start with writers approaching you with a manuscript, or do you seek out authors to bring forth your ideas?

I’m usually the one who initiates, looking for the scriptwriters to develop a story. I just published two graphic novels: “Chassé-croisé au Val Doré,” with Lewis Trondheim, and “Le Ciel dans la Tête,” with Antonio Altarriba. I have done a few books with Lewis; we love coming up with alternative narrative structures and then developing them together. Our new project, for example, is presented in a box: it is four intertwined narratives, each a thirty-two-page comic. Then, what I really like about working with Antonio is the total freedom I have when it comes to composing the page and the narrative structures of the stories he imagines.

You teach and publish in your native Spain but also in France and in other European countries. Do you think visual narratives are a universal language, or do you see specific differences in each culture?

I have always believed that the same narrative can be common in all the cultures in which I have worked as a teacher. That’s a positive aspect of globalization. In fact, as an artist, I really like to work with images without words. For example, in The New Yorker covers, the visual imagery has a universal aspect. Languages often serve as frontiers; images cut across them.

Your cover features a young dancer. Did you always know you wanted to be an artist? When was the first moment you had an inkling it would become your passion and profession?

Yes, since I was very young I have always drawn. My father used to time me while I was making drawings. I remember being an adolescent and seeing the TV series “Fame” in Spain: I understood that there were schools where students and teachers share their creative passions (later I studied Fine Arts and I am a professor at the faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Granada.) Those memories inspired this cover.

For more covers about dance in the city, see below:

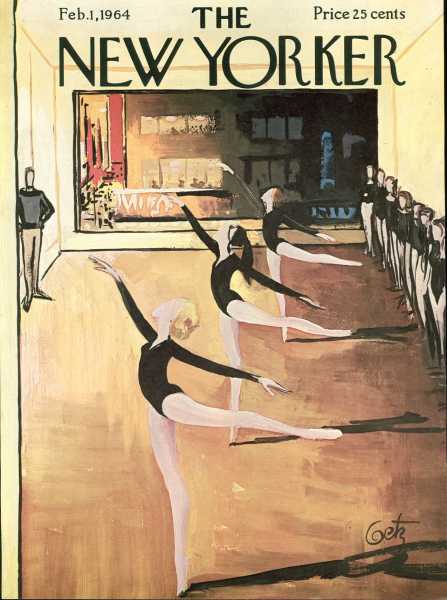

“February 1, 1964,” by Arthur Getz

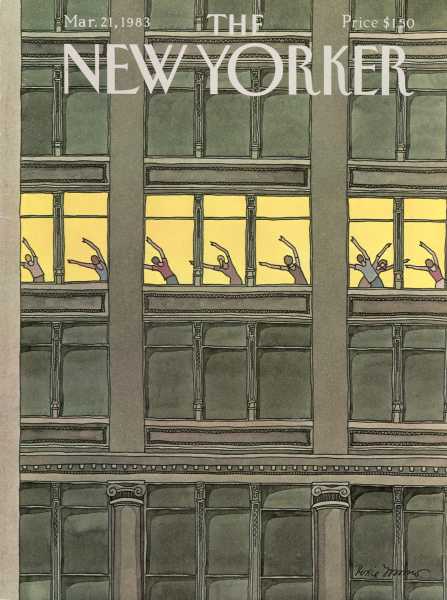

“March 21, 1983,” by Roxie Munro

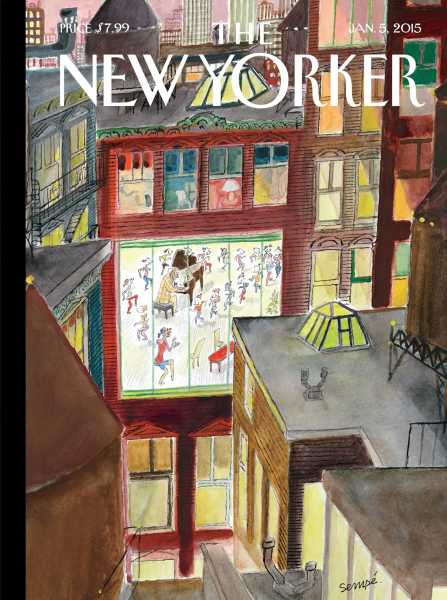

“Dance Around a Piano,” by J. J. Sempé

Find Sergio García Sánchez’s covers, cartoons, and more at the Condé Nast Store.

Sourse: newyorker.com