Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

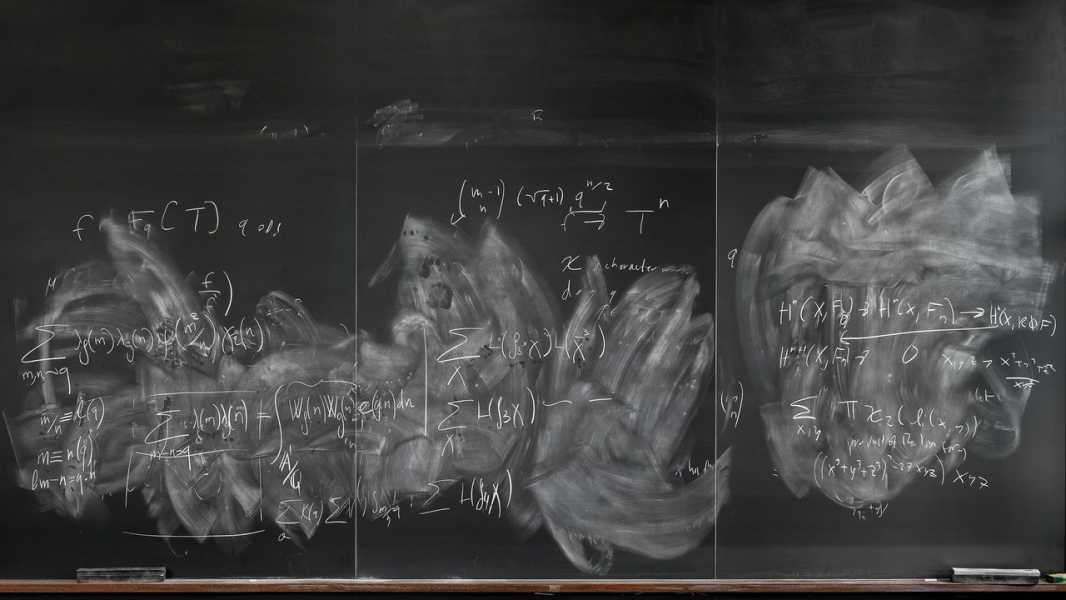

I arrived at M.I.T. in the fall of 2004. I had just turned twenty-two, and was there to pursue a doctorate as part of something called the Theory of Computation group—a band of computer scientists who spent more time writing equations than code. We were housed in the brand-new Stata Center, a Frank Gehry-designed fever dream of haphazard angles and buff-shined metal, built at a cost of three hundred million dollars. On the sixth floor, I shared an office with two other students, one of many arranged around a common space partitioned by a maze of free-standing, two-sided whiteboards. These boards were the group’s most prized resource, serving for us as a telescope might for an astronomer. Professors and students would gather around them, passing markers back and forth, punctuating periods of frantic writing with unsettling quiet staring. It was common practice to scrawl “DO NOT ERASE” next to important fragments of a proof, but I never saw the cleaning staff touch any of the boards; perhaps they could sense our anxiety.

Even more striking than the space were the people. During orientation I met a fellow incoming doctoral student who was seventeen. He had graduated summa cum laude at fifteen and then spent the intervening period as a software engineer for Microsoft before getting bored and deciding that a Ph.D. might be fun. He was the second most precocious person I met in those first days. Across from my office, on the other side of the whiteboard maze, sat a twenty-three-year-old professor named Erik Demaine, who had recently won a MacArthur “genius” grant for resolving a long-standing conjecture in computational geometry. At various points during my time in the group, the same row of offices that included Erik was also home to three different winners of the Turing Award, commonly understood to be the computer-science equivalent of the Nobel Prize. All of this is to say that, soon after my arrival, my distinct impression of M.I.T. was that it was preposterous—more like something a screenwriter would conjure than a place that actually existed.

I ended up spending seven years at M.I.T.—five earning my Ph.D. and two as a postdoctoral associate—before taking a professorship at Georgetown University, where I’ve remained happily ensconced ever since. At the same time that my academic career unfolded, I also became a writer of general-audience books about work, technology, and distraction. (My latest book, “Slow Productivity,” was published this month.) For a long time, I saw these two endeavors as only loosely related. Only recently have I realized that my time at M.I.T. may be the source of nearly every major idea I’ve chased in my writing. At the Theory of Computation group, I got a glimpse of thinking in its purest form, and it changed my life.

A defining feature of the theory group was the explicit value that the researchers there placed on concentration, which I soon understood to be the single most important skill required for success in our field. In his book “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!,” the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard P. Feynman recalled delivering his first graduate seminar at Princeton, to an audience that included Albert Einstein and Wolfgang Pauli: “Then the time came to give the talk, and here are these monster minds in front of me, waiting!” At M.I.T., we had our own monster minds, who were known for their formidable ability to focus.

I was astonished at how the most impressive of my colleagues could listen to a description of a complicated proof, stare into space for a few minutes, and then quip, “O.K., got it,” before telling you how to improve it. It was important that they didn’t master your ideas too quickly: the dreaded insult was for someone to respond promptly and deem your argument “trivial.” I once attended a lecture by a visiting cryptographer. After he finished, a monster mind in the audience—an outspoken future Turing winner—raised his hand and asked, “Yes, but isn’t this all, if we think about it, really just trivial?” In my memory, the visitor fought back tears. In the theory group, you had to focus to survive.

Another lesson of my M.I.T. years was the fundamental separation between busyness and productivity. Scientists who work in labs, and have to run experiments or crunch numbers, can famously work long hours. Theoreticians can’t, as there’s only so much time you can usefully think about math. Right before a paper deadline, you might push hard to get results written up. On the other hand, weeks could go by with little more than the occasional brainstorming session. An average day might require two or three hours of hard cogitation.

The idea of taking your time to find the right idea was central to my experience. As a graduate student, I was sent all around Europe to present papers at various conferences. The meetings themselves weren’t the point. It was the conversations that mattered—one good idea, sparked on a rooftop in Bologna or beside Lake Geneva in Lausanne, was worth days of tiring travel. But despite long periods of apparent lethargy, we still were productive. By the time I left M.I.T. to start my job at Georgetown, I had already published twenty-six peer-reviewed papers—and yet I’d never really felt busy.

Finally, there were those whiteboards. The theory group was a collection of proudly marker-on-board thinkers, surrounded by more hands-on computer scientists who were actually programming and building tangible new things. They honed concrete inventions; by contrast, our patron saint was Alan Turing, who’d completed his foundational work on the theory of computation before electronic computers were even invented. In a setting otherwise obsessed with artificial marvels, we developed a pro-human chauvinism. We were computer scientists, but we were skeptical that digital tools could be more valuable than human cognition and creativity.

The culture at M.I.T. was intense to the point of being exclusionary. If your output wasn’t laser-focussed, the system would quietly shunt you away. (The doctoral program included an ambiguous requirement called the “research qualifying exam,” which provided a natural checkpoint at which students who weren’t producing publications could move on to other opportunities.) This approach makes perfect sense for an institution trying to train the world’s technical élite, but it can’t be easily exported to a standard workplace. Most organizations are not made up of a bunch of Erik Demaines.

Still, starting from these specialized roots and then moving on to write for more general audiences, I’ve come to believe that these narrow extremes still somehow embody broad truths. Too many of us undervalue concentration, and substitute busyness for real productivity, and are quick to embrace whatever new techno-bauble shines brightest. You don’t have to spend hours staring at whiteboards or facing down monster minds for these realizations to ring true. M.I.T. is preposterous—but in its particulars it may have also isolated something that the rest of us, deep down, know is important.

“Slow Productivity,” my newest book, is ostensibly about work. It rejects a notion of productivity based on activity, and instead promotes a slower alternative based on real value produced at a more humane pace. When I wrote it, I didn’t realize that I was inspired by the eccentric theoretical computer scientists with whom I once loafed around the Stata Center. But I was. Decades later, I still think they were doing something right. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com