Why would Hezbollah enter the fight against Israel?

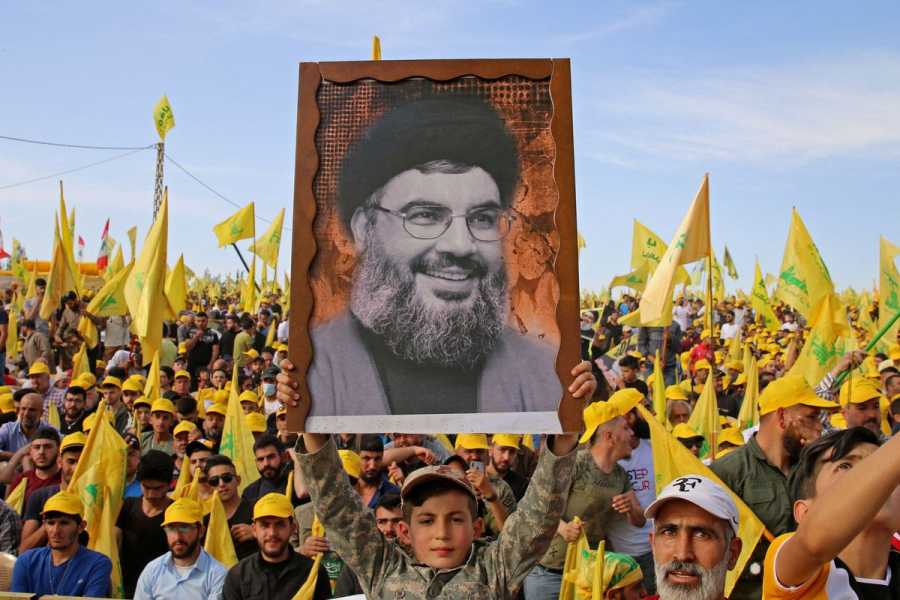

Hezbollah supporters rally ahead of the 2022 elections, raising flags and a portrait of the group’s leader Hassan Nasrallah. AFP/Getty Images Nicole Narea covers politics and society for Vox. She first joined Vox in 2019, and her work has also appeared in Politico, Washington Monthly, and the New Republic.

As Israel begins ground operations in Gaza, the potential for the conflict to expand regionally — including to Lebanon, the home of Israel’s longtime enemy Hezbollah — has heightened.

In recent days, Israel has increasingly traded fire with Hezbollah, an Iranian-backed Islamist militant organization and Lebanese political party, along its northern border. Dozens have been killed, representing the most significant escalation in violence since Israel fought Hezbollah in a bloody 2006 war. Over the past few weeks, more than 19,000 people have fled southern Lebanon in anticipation of further violence.

Hezbollah counts Hamas — the Islamist militant group that controls Gaza and launched the October 7 attack on Israel — as an ally. Both groups are designated as terrorist organizations by many countries. After Israel responded with its siege and onslaught of airstrikes on Gaza, one of Hezbollah’s top officials had a message for Palestinians trapped there: “Our hearts are with you. Our minds are with you. Our souls are with you. Our history and guns and our rockets are with you.”

But it’s not clear if that means Hezbollah, with its extensive military experience and estimated arsenal of as many as 120,000 missiles, is readying to formally enter the conflict. Should Hezbollah open a front against Israel, it would be costly for both sides as well as for their international allies, and the US has stationed aircraft carriers nearby in the Mediterranean to remind the organization of that.

Hezbollah is closely watching what Israel does next in Gaza, and if a ground invasion proves as brutal as some are predicting, it may see cause to enter the fray. On Wednesday, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah held talks with senior Hamas and Palestine Islamic Jihad leaders in which they concluded that they share a goal of seeking “a real victory for the resistance in Gaza and Palestine” and stopping Israel’s “treacherous and brutal aggression against our oppressed and steadfast people in Gaza and the West Bank,” according to a statement they released after. But the groups did not elaborate further on their intentions.

It’s a delicate moment for Hezbollah, an organization whose primary goal is eliminating the state of Israel but that has also amassed significant political power in Lebanon that it is fearful of losing.

“They can take the whole region into a very hard war,” said Abed Kanaaneh, a professor of Middle Eastern studies at Tel Aviv University and author of Understanding Hezbollah: The Hegemony of Resistance. “But they have their own interests, and they need to sustain their popularity in Lebanon. So they have their own calculations to make.”

Hezbollah’s origins and ideology, briefly explained

Hezbollah was founded in Lebanon in 1982 by men inspired by former Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s radical brand of Shia theology. The organization was among many that resisted Israel’s invasion of Lebanon that year following an assassination attempt on the Israeli ambassador to Britain orchestrated by Palestinian militants. Though the assassination was carried out by a rebel offshoot of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), a militant group, Israel sought to eliminate all Palestinian militant groups operating from Lebanon.

Following bloody fighting that left more than 17,000 dead, Israel succeeded in driving out those militants through a US-brokered agreement in 1983, which brought an official end to the war and allowed the PLO to relocate to Tunisia. But Israel continued to occupy Lebanon, creating a militarized security zone in the south that it maintained until 2000 with the stated purpose of protecting Israelis from attacks by Lebanese militants. The occupation, however, “creat[ed] conditions for the establishment and proliferation of Hezbollah,” by angering and radicalizing the local Shia community, wrote Augustus Richard Norton in his book, Hezbollah: A Short History.

Early Hezbollah supporters rally outside the bombed US embassy in 1986, listening to speeches by political and religious leaders. AP Photo

Israel set up permanent infrastructure in the security zone — military bases, new roads, road signs in Hebrew, and detention camps that Norton notes became notorious for their brutality. When militant groups including a fledgling Hezbollah tried to drive out the Israeli forces, civilians were caught in the crossfire.

Meanwhile, Iran was nurturing Hezbollah, offering it training, funding, and weapons. The Iranian government saw Hezbollah as a vehicle to indirectly attack Israel, which it regarded as an illegitimate state and encapsulation of Western imperialism, as well as a promising group that could spread their ideas of Shia Islamic revolution across the Middle East. The willingness of Hezbollah’s early leaders to pledge loyalty to Iran’s then-leaders helped facilitate bonds as well.

Hezbollah shares Iran’s Shia revolutionary ideology, and they both support Palestinians and oppose Israel. But there is disagreement among experts as to how much Iran is really calling the shots with Hezbollah. Some say Hezbollah is an Iranian proxy; Thanassis Cambanis, director of Century International and author of A Privilege to Die: Inside Hezbollah’s Legions and Their Endless War Against Israel, said their relationship can be described as “very closely allied and ideologically aligned with a lot of shared interests,” but Hezbollah also has a “great deal of its own autonomy” and “shouldn’t be understood as a traditional proxy.”

Iran has continued to fund Hezbollah over the years, and while it’s unclear exactly how much the organization has received, the US State Department estimates it at hundreds of millions of dollars annually. Most of that goes to Hezbollah’s military wing, and that figure includes weapons supplied by Iran, including an arsenal of drones and rockets. But Hezbollah also has other revenue sources, both legal and illegal: through the Lebanese state, smuggling, money laundering, and other forms of organized crime.

Hezbollah laid out its ideology in a 1985 document addressed to the “Downtrodden in Lebanon and in the World.” It identified the United States and the Soviet Union as being among “the countries of the arrogant world” that inflict suffering on those less powerful, and explicitly rejected both the East and the West. It accused the US of using Israel as a “spearhead” against Muslims in Lebanon, and justified fighting the US, often by violent means, as an exercise of its “legitimate right to defend our Islam and the dignity of our nation.” It laid out a vision for Lebanon as an Iranian-style theocracy, though it emphasized the goal of Lebanese self-determination.

And finally, it opposed any attempts to negotiate with Israel, seeking the country’s withdrawal from Lebanon as the first step toward “its final obliteration from existence and the liberation of venerable Jerusalem from the talons of occupation.” The document made clear Hezbollah saw (and still sees) Israel’s existence as a threat to Muslims throughout the region. In that sense, it found common ground with Sunni Muslim militant groups like Hamas, though Hamas’s reasons for wanting Israel destroyed were slightly different, focusing less on regional factors than on the establishment of an independent state in historical Palestine.

Hezbollah has hewed closely to this agenda in the years since, even as it has evolved from a guerrilla group to a more professionalized resistance organization, political party, and provider of social services in Lebanon. It did, however, temper its Islamist rhetoric somewhat in an updated 2009 manifesto, noting that making diverse Lebanon into a state that follows Islamic law is an unrealistic goal and affirming a commitment to “the achievement of true democracy.”

At present, Hezbollah has some 20,000 estimated active members and is popular among the Shia, who represent about a third of the Lebanese population. The most heavily armed non-state actor in the world, Hezbollah has a large arsenal of long-range missiles that can reach well within Israel’s borders, as well as a comprehensive air defense system and commando force. It has refused to give up its arms despite repeated domestic and international calls for disarmament, arguing that it needs its weapons so long as Israel continues to occupy what it claims is Lebanese territory in the Golan Heights (territory that Israel annexed in a move that has been recognized only by the US and no other country).

Hezbollah supporters and members march in remembrance of a Hezbollah soldier killed by the IDF in October 2023. Manu Brabo/Getty Images

Now, Hezbollah faces the challenge of balancing its revolutionary aims with governance — and Nasrallah, who has been at the helm of Hezbollah since 1992, has at times been criticized within Lebanon and the greater Arab world for putting too much weight on the former. But Nasrallah has also proved a charismatic leader and orator who has bolstered Hezbollah’s legitimacy through a sophisticated communication strategy and has overcome harsh criticism before.

“They are cosmopolitan and seasoned professionals, even in pursuit of problematic goals,” said Cambanis.

Is Hezbollah a militant group, a political party, or both?

The US designated Hezbollah as a foreign terrorist organization in 1997. Many other countries and organizations have followed suit, though some, including the European Union, distinguish between Hezbollah’s political and militant arms.

Some argue that’s a distinction without a difference. Unlike Hamas — in which the political and military leadership are separate and operate out of different locations — Hezbollah is a “very centrally controlled, unified organization,” Cambanis said.

“Their political leaders all have a military background,” he said. “Their resistance structure, to use their term, necessitates the armed struggle and the political struggle being inextricable.”

Hezbollah became associated with terrorism in the 1980s, during a time when it rejected the notion of participating in Lebanese politics. It viewed the political system, which was designed to split power between the country’s largest religious groups based on their size at the end of France’s dominion, as irredeemably corrupt and unfair. So Hezbollah dedicated itself to pursuing the objective of replacing the secular government with an Islamist one.

Its first step was ridding Lebanon of the foreign influences it believed to be the source of political strife: France and the US. Both countries had deployed peacekeeping forces to Lebanon amid the 1982 Israeli invasion and outbreak of civil war. From the US perspective, the most devastating terrorist attack was a 1983 suicide bombing on its military barracks in Beirut, an event that killed more than 300 American and French troops and Lebanese civilians. The Americans blamed Hezbollah for the attack and pulled all of their forces from the country. There was also the June 1985 hijacking of TWA flight 847 to Beirut, in which militants who later escaped without being captured killed a passenger and threatened to kill more unless Israel released hundreds of Lebanese prisoners. (Hezbollah denies involvement in either incident.)

US Marines and aid workers sort through the wreckage of their bombed barracks in October 1983, looking for survivors and the dead. Peter Charlesworth/LightRocket/Getty Images

Between 1982 and 1992, Hezbollah took more than 100 foreign hostages, mostly Westerners, seemingly with the aim of winning concessions from Western countries. In one such incident, known as the Iran-Contra affair, then-US President Ronald Reagan traded weapons to Iran, which was then subject to an arms embargo, for the release of hostages held by Hezbollah. Hezbollah also kidnapped Israeli soldiers, conducted cross-border raids on the Israeli border, and fired rockets and missiles into Israel, again with the goal of ending Israel’s occupation.

Those tactics continued through the 1990s, even as Hezbollah changed its strategy and decided to enter politics. Hezbollah members were elected to the Lebanese Parliament for the first time in 1992, following the end of the 15-year Lebanese civil war that had seen various religious and secular subgroups clash. It was then that Lebanese leaders associated with Hezbollah came to recognize the “need to come to a modus vivendi with the state rather than remain outside the political system and judge it as abhorrent in strictly Islamic terms,” Norton wrote.

Interestingly, Hezbollah built its political following on non-religious themes, which Norton identifies as “battling economic exploitation and underdevelopment, inequities in the political system, personal freedom and opportunity, and, of course, security.” But it wasn’t until after 2000, when Israel finally withdrew from the security zone it had established in southern Lebanon, that Hezbollah really gained popularity.

Though Israeli leaders insisted that their withdrawal from Lebanon was a unilateral political decision, many Lebanese credited Hezbollah with driving out the army by stepping up its attacks. That — along with Hezbollah’s investment in schools, clinics, youth programs, and other social services — drove up the organization’s profile in Lebanon. It went on to progressively gain seats in Parliament over the years and to run a coalition government alongside its sometimes political rival Amal, which also draws its power from Lebanon’s Shia community. In the most recent Lebanese elections in 2022, Hezbollah won 13 of 128 seats, though the party and its allies lost their majority.

Still, Hezbollah’s emergence as a political force didn’t mean that the group abandoned its violent tactics, at times undermining its authority as a resistance group. For instance, the United Nations found that four Hezbollah members were responsible for the 2005 assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in a car bombing that also killed 21 bystanders. And in 2006, the organization killed three Israeli soldiers and kidnapped two others in a cross-border raid. It failed to anticipate the disproportionate Israeli response and the ensuing war, which claimed the lives of more than 1,000 Lebanese and 160 Israelis. Neither side won; a UN-brokered ceasefire ended the conflict after a little over a month.

A Lebanese man surveys the damage around him after a July 2006 Israeli airstrike. Issam Kobeisi/AP Photo

Hezbollah has also proved willing to enact violence at the behest of Iran’s proxy networks, especially following its involvement in the Syrian civil war defending the Assad regime and after the 2020 assassination of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps commander Gen. Qassem Soleimani. Hezbollah has deployed militants to other countries — including Iraq and Yemen — to train these proxy groups and fight alongside them.

Along with Iran, Hezbollah is closely linked to Syria, though their relationship has been more one of convenience than shared ideology. Syria has long served as a conduit for weapons supply lines between Iran and Syria. As a result and at Iran’s urging, Nasrallah committed Hezbollah to “do everything in [its] power” to protect dictator Bashar al-Assad’s government from largely Sunni rebel groups after civil war broke out in 2011.

Hezbollah helped turn the tide of the war in Assad’s favor. When they withdrew most of their forces from Syria in 2019, they left arguably stronger militarily than they were before — raising concerns that they could pose a formidable foe should they enter the conflict with Israel.

Syrian soldiers patrol the streets of Qusayr after their allied Hezbollah’s forces led an assault that destroyed rebel positions in the city. AFP/Getty Images

Hezbollah’s standing — domestically and internationally — is not what it once was

Although Hezbollah’s military wing came out of the last two decades of conflict battle-hardened, its violent adventurism has caused its political wing a lot of harm.

Hezbollah lost some of its luster domestically and regionally as a result of the 2006 war’s death and destruction. In addition to the many casualties, Israeli attacks led to $2.8 billion in direct damage. While Hezbollah (using funding from Iran) poured hundreds of millions of dollars into compensation and rebuilding efforts, Lebanon still took years to recover. The organization’s involvement in Syria hurt it politically, too. In Lebanon, voters believed that foreign intervention had come at the expense of their domestic concerns, and throughout the region, Sunnis expressed great disillusionment with Hezbollah; they saw the group as having propped up Assad, a vicious leader who routinely oppresses his people.

In recent years, Hezbollah’s political capital has been further reduced by political issues. Mass protests spurred by economic troubles undermined support for Hezbollah and the country’s political elites in 2019. Prime Minister Saad Hariri resigned under public pressure, despite Hezbollah’s desire to keep him in office. Hezbollah members actively sought to suppress the protest movement, setting fire to a camp of anti-government protesters.

Hezbollah’s popularity again took a hit following the 2020 explosion of a Beirut port, which the organization controlled. The group also resisted calls for an international investigation of the incident, much to the chagrin of the Lebanese public. Ahead of the 2022 elections, Hezbollah’s role in Lebanon’s general political instability had many of its opponents deeply frustrated.

A protester burns a poster featuring Hezbollah leaders (including Nasrallah) and other government officials in a 2022 protest demanding justice for victims of the 2020 explosion. Anwar Amro/AFP/Getty Images

Even before these issues, Hezbollah was a polarizing force in Lebanese society. The organization has solidified Shia support by being effective in local government and supporting social services but has often struggled to expand its sphere of influence. Lebanon is a fractured society, with different religious and secular groups jockeying for power, and Hezbollah is hated by those who oppose its worldview, with little room for a middle ground.

“They are successful at winning very deep loyalty from their supporters,” Cambanis said. “And they’re successful at being able to violently coerce and intimidate their opponents.”

In a 2021 Zogby/NC State University poll, 52 percent of Lebanese said they did not think Hezbollah promotes stability, though significant majorities of Shia, Druze, and Christians — all groups with leaders who’ve partnered with Hezbollah in the past — said that it did. The question is whether these cracks in Hezbollah’s support can be contained as the organization faces the prospect of an all-out war with Israel.

“Lebanese are okay with the limited war that Hezbollah is [waging] against Israel right now, but if it will become total war or much deeper war, I can say that Hezbollah’s support will drop off,” Kanaaneh said.

Will Hezbollah enter the Israel-Hamas war?

Hezbollah has been reluctant to engage Israel in open combat since the devastating 2006 war. But the situation in Gaza could change that.

The main factor in its decision-making will be how ground operations in Gaza play out and to what extent Israel brutalizes the civilian population. Hezbollah has “built their own narrative and public image of being part of the resistance axis” around the Palestinian cause, and it would be difficult for them to stand by while Israel once again militarily occupies Gaza and attempts to eradicate their Sunni ally in Hamas — its link to the broader Islamic world, Kanaaneh said. That might be particularly true following the mutual commitments reached in Wednesday’s summit, even as other Lebanese politicians urge Hezbollah against getting involved in a war that their country cannot afford.

That suggests that Hezbollah is, at this point, “primed for an escalation,” Cambanis said.

A family, displaced from souther Lebanon by Israeli strikes as part of the IDF’s October 2023 battle with Hamas, poses for a portrait in the Tyre school that’s been converted into a shelter. Manu Brabo/Getty Images

“Their escalatory moves suggest they are, in fact, as committed as in earlier stages to fighting Israel, even if it is bad for Hezbollah’s community,” he said. “And even if it’s bad for Hezbollah’s short-term organizational stability, it seems like they really are actually, genuinely believers in their endless fight against Israel.”

If Hezbollah gets involved in the war, it could play out much like the 2006 conflict where there were no victors, though it could potentially be even bloodier. In 2006, Hezbollah was estimated to have 12,000 missiles; now, it is thought to have 10 times that. Its troops have far more experience, including in urban combat, than they did before. And while Hezbollah was riding a wave of popularity in 2006, it now needs something it can hold up as a win that would allow it to restore itself to its former glory.

Regardless of how any fighting turns out, “everybody will lose from this,” Kanaaneh said. That may include Kanaaneh himself: He lives in Israel near the Lebanese border.

Sourse: vox.com