As a child, I knew only that my grandmother had died when my mom was still a baby. The one time I asked what had happened to her, a bolt of panic flashed across my mother’s face. “A household accident,” was all she said.

I was twelve years old when she finally told me the truth. Some friends and I had got into a long after-school discussion about abortion, prompted by the gruesome posters that a protester had staked in front of the Planned Parenthood in our Vermont town. I had already begun reading my mother’s Ms. magazines cover to cover, but this was the first time I’d encountered a pro-life position. When I hopped into my mom’s car after school, I was buzzing with new ideas. I had almost finished repeating one friend’s pro-life argument when I saw the look on Mom’s face. That’s when she told me: the “household accident” that had killed her mother had, in fact, been a self-induced abortion.

Her hands were tight on the steering wheel as she spoke. I realized later that it wasn’t the topic of abortion itself that made her so uneasy—she was a nurse and a Roe-era feminist who usually responded straightforwardly to even the most embarrassing health questions. Rather, her anguish arose from sharing a truth that she’d been brought up believing was too terrible to speak.

Sitting beside her in the passenger seat, I struggled to absorb the meaning of what she’d told me. I had only just grasped what abortion was a few hours earlier, and was still trying on this new pro-life idea. “O.K.,” I said, “but what about the uncle or aunt I never had?” Mom whipped toward me, face taut with a rage and fear that I somehow understood had nothing to do with me. “What about the mother I never had?” she said.

Until recently, everything my mom knew about her mother fit into one three-ring binder. Inside were letters, documents, and photos that my mother had collected over the years. After the election last fall, as an Administration hostile to women’s reproductive rights settled into the White House, I asked her to send the binder to me, and did some sleuthing of my own. I got in touch with aging relatives and family friends, who offered crumbling bundles of my grandmother’s letters, carefully preserved for decades. My questions about her life and death hadn’t changed since I was twelve years old. What felt new, in the Trump era, was the urgency of her story.

My grandmother, Winifred Haynes Mayer, was born in New York City, in 1912, to an upper-middle-class family. Her father, a doctor, spent time in France during the First World War, helping set up orphanages, and returned to the U.S. in love with a Frenchwoman and seeking a divorce. Win and her brother were raised in the Bronx by their mother, Nyesie, a nurse.

Nyesie was determined that her daughter receive a college education, and in 1929 Win enrolled at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. There she majored in English, helped found a literary magazine, and, in her senior year, met my grandfather, Eddie. Win was lean and athletic, with high cheekbones and windblown hair. In photographs, she always looks as though she’s just returned from a brisk stroll.

Win and Eddie married in 1939. She got pregnant immediately but miscarried after her doctor prescribed some medication, possibly for morning sickness. In a short letter to her mother, dated “Thursday, I guess,” she wrote, “I lost the little kangaroo early Wednesday morning and am now lying in an empty and ethery tearful state of mind.” Nyesie wrote back, with some words crossed out, “I wish so much that I were near enough to be useful to you.”

My uncle Peter was born in 1941. (“He is a very funny looking little squirt but we like him,” Win wrote Nyesie. “Are there any chipmunks in our family?”) Soon after the United States entered the Second World War, Eddie was recruited by the newly formed Office of Strategic Services, and the family moved to Alexandria, Virginia. They rented a small apartment from some friends, Katrina and Chandler Morse, whose rambling house was a gathering place for a community of O.S.S. families.

Sooner or later, they knew, Eddie would leave for London. But the dates and duration of his deployment kept changing, and the uncertainty began to wear on Win. With Eddie away on a three-day business trip, she noted, “I am getting a foretaste for which I do not particularly care.” When he finally departed in April, Win was seven months pregnant with my mother, Judy. Eddie would not meet his daughter until she was six months old.

Katrina, their friend and landlady, needed the apartment for her sister-in-law and infant niece, so Win moved away, to a nondescript block of Army housing. She spent the summer of 1943 caring for her two children alone in the thick Virginia heat. Her letters to Nyesie convey a parent’s mix of joy and fatigue. “Judy is a sweet, juicy little girl as ever,” she wrote. “She howls from 7 till 8:30 which is very dull because by then I am fed up with children and want only to sit on the front porch in the cool of the evening.”

Eddie’s letters indicated that he’d likely be returning in November, but that month came and went with no sign of him. Then, just before Christmas, Win’s neighbor ran over to relay an urgent message from Katrina—she’d heard, through the O.S.S. grapevine, that Eddie was on a flight home. Win quickly cleaned the house, and then rushed with the children to the grocery store. When she called Eddie’s office from the A. & P., they told her he was waiting at the train station. “So we all dashed in to meet him!” she wrote to her mother. “T’is wonderful to have our family whole again.”

It wasn’t to last. Eddie’s commanders had decided that his project would require him in Europe indefinitely; once deployed, under the best scenario he’d have short leaves every six to eight months. “I really don’t think the Lord would have had to try boils to find the limit of my endurance after that,” Win wrote. That winter, a preoccupied tone crept into her letters to Nyesie: “I . . . heard from Beth that Winston had been killed over Munster . . . and that his widow has had twins, a boy and a girl,” she wrote. “Birth and death follow each other so swiftly these days that one has no time for the appropriate feelings about either of them.” A few weeks later, Win learned that she was pregnant again.

This pregnancy, unlike the others, is never mentioned in her surviving letters. Nyesie came to visit the first weekend in April, and it’s likely that Win asked her in person for help in obtaining an abortion. This would not have come as a shocking request. Nyesie was part of a large social circle of progressive doctors and nurses, and she would have known which of her colleagues might be willing to perform a “D. and C.” in violation of the law. In the nineteen-thirties, she had arranged an abortion for her son’s wife, an actress. The couple had gone on to have two daughters.

Nyesie agreed to help Win. The next weekend, Win left her children in Virginia and travelled to New York. But, at the last moment, for reasons that have been lost, the arrangements Nyesie had made fell through. Win then turned to another New York physician she hoped might be able to help—her father. He refused. Eddie later told my mom that Win’s French stepmother had offered her this advice: “Frenchwomen take care of these things themselves.”

Back in Virginia the next Sunday, Win went with Eddie and the children over to Katrina’s house. The weather was cool and gray but the peach trees were in full bloom. Katrina wrote to her husband, who was stationed in London, “The maples are covered with their funny yellow-green flowers and the grass is that beautiful soft lush spring green.” Win left no record of what she was thinking or feeling that weekend as the others tilled the garden while the children napped in a hammock. But when I imagine her these are the things I think about: of how provisional and precarious early pregnancy feels, even when welcomed with more joy than fear; of how everything during that time narrows in toward the dark knot at your center, the turning point of your whole future; and of desperation, the kind that manifests not in panic but in a calm practicality. Of how plain the way forward can feel in those moments when other options have evaporated.

That Tuesday, April 18, 1944, Eddie went to work as usual. At noon, Win gave the children lunch and put them down for their naps. Then, as though it were any other task that needed to be completed during her few hours of solitude, she went into the bathroom. The sharp object she took with her—a knitting needle?—is another detail that has been lost. That evening, Katrina was coming home from the Washington Nationals’ opening day. “As I walked across the porch into the house from the game . . . the phone was ringing,” she wrote to her husband. “It was about 6:45. I let the phone ring while I went and let the dogs out who had been shut in our bedroom all afternoon. As I picked up the phone Eddie Mayer’s voice came to me saying, ‘Katrina—can you come right over. I think Winnie is dead.’ ” Eddie had arrived home from work to find his wife crumpled in the bathroom. Nine-month-old Judy was still in her crib, crying, but two-year-old Peter had been out of bed and wandering around the apartment for hours.

“The true cause as stated by the autopsy is ‘death due to shock as a result of an attempt to force a miscarriage by mechanical methods,’ ” Katrina wrote to her husband. “But the party line which we are following and telling every one is death caused by an embolism.” My mother would not learn what really happened for more than two decades. In lieu of an explanation, adults offered confusing half-truths that conveyed no clear message apart from their own guilt and shame. Once, Nyesie sat her grandchildren down in the living room to tell them the story, mixing the truth of the abortion with the lie of the embolism in a way she apparently thought that they could handle. My mom was five years old at the time. Almost seventy years later, she recalled the scene to me in detail: how she was sitting on the floor, looking up at her grandmother on the couch, backlit against the living room’s bay windows. “What I understood was that there was a baby and a bubble,” my mom told me. Her grandmother offered no follow-up, and the children had long since learned not to ask questions. Peter, who was seven years old, decided that his mother had died of cancer. But my mother heard something different: she knew that she had been a baby when Win died. It took her decades to shake the conviction that she’d been the cause of her mother’s death.

“It took all my courage and energy just to bring up the subject the few times I did,” my mom recalled. As a junior at the University of Hawaii—the farthest-from-home college she could find—she wrote her father a letter, demanding at last to know the truth. It arrived the same day Eddie found out that his own mother had died. “I’m so grateful for your having written,” he wrote. “It’s as tho I’ve been pulled back from a terrible brink of loneliness & lack of communication & hopelessly tumbling over the edge into the void.” But it wasn’t until he visited her a year later that she dared to bring it up again. She was the exact age that Win had been when Eddie first met her, and they bore a startling resemblance. As my mom remembers it, “I was driving my car from the Waikiki side to the Kailua side of Oahu when I told him that I wanted to know how Win had died.” In clipped sentences, he told her the truth. She reached over to grab his hand, but he shoved it back at her. Eddie lived for another forty years, but they never spoke about Win’s death again.

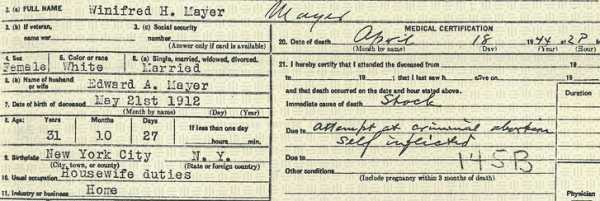

It was in the feminist movement of the nineteen-seventies that Mom found, for the first time, other women who were determined to talk about abortion—not in hushed tones but as a matter of health care and family planning. Three years after the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade, when I was a few months old, she finally sent away for her mother’s death record. Under “cause of death,” the coroner had written in a sloped hand: “Attempt at criminal abortion, self-inflicted.” The word “criminal” refused to sink in. “That night, for the first time in many years, I vomited several times,” she told me. “Somehow I knew I wasn’t sick, but was having a life purge.”

Winifred Haynes Mayer’s death certificate.

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY KATE DALOZ

Several months before the election, my own seven-year-old daughter asked me how her great-grandmother had died. Already, there’d been reports of a rise in self-induced abortions in states where access had been restricted. Despite years of thinking about Win’s death and how to talk about it, I was caught off guard by her question. We were on the street. I was wrestling car keys out of my purse with one hand while trying to keep a grip on my toddler son with the other. Like my own mother before me, I hesitated.

To understand Win’s story—what had happened to her, what she had done, and why—my daughter would need a number of moral and biological concepts that were not yet in place in her young mind. Still, I wanted to offer her a simplified version of the truth that could remain stable for her as she got older. I wanted to assure her that, even though this was a story she needed to grow into, she should always feel free to ask questions, and that I would answer as honestly as I could. And I wanted to break my family’s long-standing silence surrounding Win’s death, because silence only helps to perpetuate the fallacy that outlawing abortion has ever stopped women from attempting it.

If I couldn’t immediately explain to my daughter how Win died, I decided, I could at least explain why. “She needed help really badly and no one would help her so she died,” I told her. Then I added a reassurance that I’m not sure I’d feel confident offering today. “It’s not a thing that would happen to us now,” I said. “If we ever needed that kind of help, we would get it and we would be safe.”

Sourse: newyorker.com