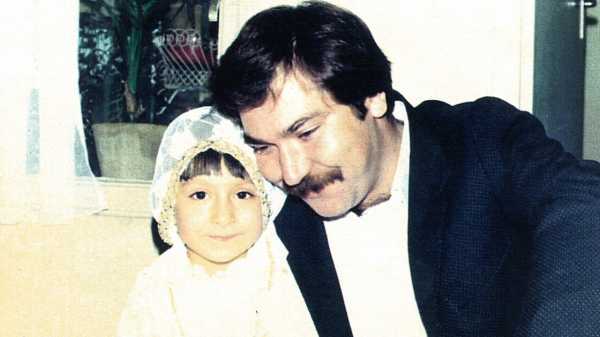

In my early years, my father and I were partners in crime. Every night I

would wait for him on the stoop of our house in Isfahan, Iran. I would

tease him by greeting the melons and sour cherries hidden in his coat

before saying hello to him. We would sneak ice cream together, eating it

with spatulas in the bedroom so my mother wouldn’t see. I walked

barefoot on his aching back. I was always on his lap at dinner tables. I

have his chin, his eyes, his smile that looks as if it belongs on a

six-year-old’s face.

In 1987, when I was eight, my mother, brother, and I escaped our home.

My father was rooted to his childhood village, and, when we found out

that it was harder for entire families to leave together, he stayed

behind. On our way to the airport, we were driven past my father’s

dental office so we could wave goodbye to a darkened figure in a

third-floor window. My encounters with him since then have been brief;

I’ve seen my father four times in thirty years, for a total of forty

days, give or take. The first visit was in Oklahoma, a year into our

American asylum. I was eleven and everything had changed. I had lived in

refugee hostels. I had learned English and endured the South. I refused

to let him touch me or kiss me. This must have stung the most—he is a

hugger, a kisser. He wanted to pick me up and wave me around like he

used to do, to squeeze my face and bite my cheek and check my teeth. I

hardly said hello, arms crossed over my very American T-shirt. At that

age, all I wanted was to disappear, but this stocky, red-haired,

mustachioed man had shown up ready to experience America loudly. He ate

ice cream twice a day, counted the price of everything by the number of

root canals he would have to perform to earn it. Despite our shared

bookishness, he laughed at the intensity of my ambition to go to Harvard

or Yale. He offered pistachios to the plumber. Though we lived in a

small town, he found Iranians with whom to drink and recite poetry until

the early hours. He bought us season passes to a local waterpark, where

he spoke loud, boisterous Farsi and flashed a wad of cash wrapped in a

rubber band. He stood shirtless by his deck chair, hands on hips, pale

body covered in red hair, surveying the place. When he asked me to apply

sunscreen to his back, I gave him a few cursory dabs and stopped the

instant the stuff started to foam.

Later, as we ate lunch on the balcony of a rib joint, I noticed a

teen-ager loitering near our table. Without a word, my father got up,

gave him two cigarettes, and returned to the table and tore open his

daily Twinkie. Later, when I caught the same kid trying to jimmy open

our locker, I realized Baba had been giving loose bills and cigarettes

to gangs of teen-agers in exchange for beach chairs and towels and

errands. I was mortified. Soon, he became addicted to one of the scarier

waterslides, one that included a second of free fall. “That slide is

like a shot of whiskey,” he said as he breezed by us. But Baba had a

taste for stronger substances, and, even in a foreign town, he knew

where to look. On the last day before he left, I found him in a trance,

slumped on the bathroom floor, sweating through his shirt, his eyes far

away.

The second time he visited, I was fourteen and had adopted a rigorous

Tae Kwon Do practice as part of my Ivy League entrance strategy. I never

smiled. I baffled him. My brother kept protesting about his cigarettes.

Neither of us asked about Iran. Baba was older, of course. His age was

jarring—his bulbous nose, the unnatural arc of his back, his varicose

veins and hashish smell. I saw more clearly the risks he took, the

smuggled caviar and pipes sewn into his suitcase lining, the phone calls

to random Iranians who lived nearby, the foggy spells. I kept my

distance and hushed him when he spoke Farsi.

He took us to a restaurant called Shogun, and when he started on the

sake I demanded to go home. He said, “Next time, before I visit, maybe I

should stop in Dallas for a brain disinfection and stomach pump, to wash

away all the embarrassing Iranian things.” Later, he asked why I had

chosen to play a boy’s sport. I explained that fewer girls competing

meant I could win more trophies and get into Harvard. “Huh,” he said.

And then, “Enjoy this life, Dinajoon.” He downed more sake. A few days

later he brought home some nails. “These are to nail down your good

name,” he said, “So you can stop worrying about misplacing it all the

time.”

Within a few days, he seemed exhausted by our piece of America. When my

mother’s church tried to convert him, he said “O.K., I believe,” and let

them baptize him the following Sunday. He made a good show of it,

brandishing his Bible. In private, he said, “Dinajoon, this God business

will mess you up. There are two things in life: science and poetry.”

In 2001, Baba tried to come to my college graduation. His visa

application was rejected in both Dubai and Istanbul. In 2003, he tried

to come to my wedding. That visa request also failed. I wrote to Hillary

Clinton, explaining all my efforts and asking for help. An intern called

me back and sent me to the U.S. immigration Web site. Secretly I was

relieved, not in small part because we were now living in the age of

suitcase scans. I left a seat empty for him at my wedding: place card,

chocolate box, napkin.

The third time, we met Baba in London. I was twenty-five and my brother

Daniel, twenty-two. Daniel had just graduated from N.Y.U. and was

working in publishing. I had just left my job as a strategy consultant,

at McKinsey & Company, working fifteen hours a day, to take a job as a

strategic manager at Saks Fifth Avenue. I was a Princeton grad with a

job managing people twice my age. I had just married my college

boyfriend, a man who definitely thought his family was better than mine.

I was proud, and insecure, and insufferable.

My brother and I were so preoccupied with our new lives in New York that

we almost missed the fact that our father had brought his second wife

and a two-year-old daughter to London. What did we have in common with

an overindulged, fat little Iranian girl begging for Kit-Kats? We were

children of asylum and borrowed books and multi-variable calculus, of

the Socratic method and cram sessions and lecture halls and alumni

grants. We had hard bodies and East Coast brains and pale-faced partners

who believed in themselves and adored us for our neuroses. My new

stepmother wore floral-print polyester, her toenails painted cherry red

and a touch too long. Her daughter’s accent was atrocious. “Babajoon,

stop calling her my sister,” I told my father. I asked him to enroll his

daughter in an English class. He dropped his head, nodded, and said, “I

hope one day, maybe with your new husband, you learn to enjoy this

life.”

The next day, in the National Portrait Gallery, I started to panic—for

many reasons. The only one I revealed to Baba was that I had

accidentally taken an extra birth-control pill. “Is just hormones,” he

assured me. Then he asked to see my pills. Before I could object, he had

eaten one. “See? Now we both took one too many.”

The fourth time, we met in Istanbul. I was living in Amsterdam with my

husband, who had begun to spend all his time at work but who made our

lives comfortable in ways I had never before experienced. My brother,

too, was married. This time, we brought our partners. Philip and I were

coming from Amsterdam, Daniel and Alexandra from New York, and Baba from

Isfahan. We had rented three rooms in the old district of Istanbul, and

our flights were arriving two hours apart from each other: first Baba,

then my brother and his wife, then us. Philip and I went to reception

and asked if our party had arrived. The manager, a Turk who had

obviously worked in service for decades, glanced at Philip’s Barbour

jacket and European haircut, then back at the roster and said, “No.

We’ll let you know when.”

So we checked in, dropped our bags in our room, and went for a walk. An

hour later we checked at reception again. The man said our party still

hadn’t arrived. Another walk. The hotel was situated on a beautiful

tree-lined side street overlooking the Hagia Sophia. Up above was a

balcony café where, from across the road, I saw an old man leaning over

the railing, a cup of Turkish tea in his hand. He had a cane and gray

hair. He looked in another world, but when he saw me, he jumped up and

rushed down to us, hobbling on his cane, looking at my husband with

admiration. I hugged him and introduced him and he tried, with his few

English words, to express to Philip his happiness to see us.

When he told us that he had arrived hours ago, I stormed off toward

reception. The manager was already watching us. He apologized,

explaining that, since we were a European couple, he had been waiting

for someone else for us, and for an Iranian family to meet my father. I

asked, again, whether it was possible that my brother had also arrived.

“Well,” the receptionist said. “There’s an American couple.”

My brother, too, had arrived hours before. Finally reunited, we set off

to see Istanbul. My father was thoroughly charmed by Alexandra, Daniel’s

pretty blond American wife. Arm in arm, they whispered and sampled

sweets together. She called him Babajoon, in her American accent; he

called her daughterjoon. It hurt a little.

Again, I was struck by his age. He used counting beads. His memory was

fading, and he complained that the meat wasn’t cooked right—we had to

eat at the same kabob house, Hamdi, every night. Soon we had amassed a

large collection of the restaurant’s wet naps, which my brother called

Hamdi wipes. I laughed. Baba didn’t get it. “What is funny about Hamdi

wipe?” He spoke to us in poetry and in food. He taught Philip a poetry

drinking game. He said in broken English, “Philip, my son, you take

Hafez book”—he had brought it in his suitcase—“and you take shot. You

ask a question about future. You open book. Your answer is on that

page.” We played the game all night. Daniel tossed his shots into the

plant while Philip and my dad got drunk together, threw their arms

around each other, and predicted the future. This was something they had

in common: the easy ways of men who had once been the golden child of

their respective families.

One night we went to see some whirling dervishes. My father adores Rumi;

if he didn’t hate religion and believe himself to be his own god, he

would be a follower of the Mevlevi order. Enraptured, he watched the

dervishes, his counting beads turning in his fingers, his head nodding

in meditation. Behind us, a group of Americans chatted, reading aloud

from guidebooks and wondering when it would end. I knew Baba was

annoyed. The Americans behaved with such entitlement that it took me ten

minutes to find the courage to overcome the sense that it was my family

who was out of place, my father who was embarrassing. Finally, I turned

to the family and said, “This is a religious ceremony. Be quiet or

leave.” My father looked at me aghast. He whispered, “Dinajoon, let

everyone enjoy it their own way. Americans enjoy by talking.”

On the last day, we left in shifts. First a car arrived for Daniel and

Alexandra. Philip, my father, and I had a quiet lunch on the balcony,

and the staff was extra attentive. My father’s head hung a bit lower.

His six-year-old smile was gone. We got free cappuccinos. Then our car

came. We climbed in, promising Baba that we would meet again. From the

back of the car, I turned to wave goodbye. I expected to see him

standing alone in the road but two hotel staffers had him by each arm

and were escorting him to the balcony, where strong Turkish teas had

awaited him all week. He wiped his face with a swollen hand, his ring

glinting in the sun.

For many years after, we didn’t talk. Daniel had a baby who became a

toddler. I moved to New York again. Daniel tried to see Baba again in

Dubai, but Baba didn’t buy the plane ticket. We heard that he married a

third time, a woman two years younger than me. Then I had a baby, too,

and he got back in touch. I was in Provence for the summer and he

promised to come see me. As had happened with my brother, he didn’t even

book a ticket. It’s been years since we’ve seen each other, and much has

changed. My brother and I have suffered failures, a divorce (mine), the

pain of children, how they hold your heart in their sticky, careless

fists. I know that Baba will never live in the West with us. It would

end him, his big personality, his glorious sense of himself. He knows

this, too; maybe that’s why he no longer buys tickets to see us. But he

has Instagram, and he writes messages for my daughter in Farsi, using

English letters. Every few days, his name pings on my phone screen. Dr. Nayeri commented on your video. Dr. Nayeri likes your photo.

Sourse: newyorker.com