Kim Kardashian West did it: President Donald Trump has commuted the life sentence of Alice Johnson, the 63-year-old great grandmother in prison for drug trafficking, whose cause Kardashian lobbied for in the Oval Office.

The commutation, confirmed by the White House, comes quite quickly after Kardashian’s meeting with Trump in the Oval Office last week, which Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, arranged so the pair could talk prison reform and Johnson’s potential pardon.

Trump’s move is all the stranger because it goes against the broader policy that Trump has been pushing for drug dealers and traffickers. In response to the opioid epidemic, Trump has said that the government should execute drug dealers and traffickers. More broadly, his administration, under Attorney General Jeff Sessions, has adopted a “tough on crime” view toward drugs.

But it adds to the unusual string of pardons and commutations that Trump has carried out since he took office last year — typically to friends or allies or, as seems to be true in Kardashian’s case, causes embraced by friends and allies. That kind of nepotism has reportedly horrified even some of Trump’s top advisers, according to Ashley Parker, Robert Costa, and Josh Dawsey at the Washington Post:

Regardless, the Post’s reporting suggests that more of these pardons and commutations are coming. And the president seems to be giving little thought — besides “asking friends who else he should pardon,” according to the Post — about the implications for his broader policy agenda.

Who is Alice Johnson?

Johnson has been serving a life sentence for a first-time, nonviolent drug offense. Since there’s no parole in the federal system, she’s not eligible for it. Johnson, who was sentenced in 1996, has already been in prison for more than 20 years.

Her case was documented in a video by Mic:

According to the Associated Press at the time, Johnson helped lead a multimillion-dollar cocaine ring from 1991 to 1994. At her sentencing, US District Judge Julia Gibbons said that Johnson was “the quintessential entrepreneur” in the operation, “and clearly the impact of 2,000 to 3,000 kilograms of cocaine in this community is very significant.” She was tried on cocaine conspiracy and money laundering charges.

Johnson told Mic that she got involved in the drug trade at a particularly bad time in her life. Her son had died in a motorcycle crash, and her marriage had ended in divorce. She also had lost her job, causing financial strain. “I couldn’t find a job fast enough to take care of my family,” she said. “I felt like a failure.”

The damage done by the prison sentence is permanent, Johnson said: “I missed the birth of my grandchildren, being able to be in their life. I just had a great-grandson. I missed that. Both of my parents had passed away. I was not able to be by either of their sides in their final days. That’s an ache that I can’t — that never goes away.”

Kardashian first heard of Johnson’s case through Mic’s reporting, tweeting in response to the video, “This is so unfair…”

According to Mic, Kardashian then approached her lawyer to help deal with the case and has communicated directly with Johnson. Johnson subsequently wrote an op-ed for CNN in May titled “Why Kim Kardashian thinks I should be released from prison.”

Johnson acknowledges that she did something wrong. The question, for her, is if she should really spend the rest of her life in prison for a nonviolent offense.

“The real Miss Alice is a woman who has made a mistake,” Johnson said. “If I could go back in time and change the choices that I made and make different choices, I would. But I can’t. But what I have done is I have not allowed my past to be the sum of who I am.”

Johnson’s case isn’t the first to trigger outrage over excessive prison sentences. Weldon Angelos was sentenced to 55 years in prison for selling marijuana while allegedly in possession of a firearm — a sentence that drew criticism from not just criminal justice advocates but also politicians and even the judge who sentenced him, leading to Angelos’s early release after 12 years in 2016.

In the past few weeks, the case of Matthew Charles has also made headlines after Charles was ordered back to prison after two years out because, a federal appeals court concluded, he was initially released early in error. Kardashian has also tweeted about Charles’s case.

It’s unclear, though, if she brought up Charles’s case in her meetings at the White House.

Trump’s commutation of Johnson contradicts his criminal justice policy

Trump’s commutation of Johnson is all the more bizarre because it goes explicitly against his broader policy agenda.

As president, Trump has argued that drug dealers and traffickers, like Johnson, should be executed because, in his view, they’re guilty for the overdose deaths that their drugs cause. As he put it at a rally earlier this year, “If you shoot one person, they give you life, they give you the death penalty. These [drug dealers] can kill 2,000, 3,000 people, and nothing happens to them.”

Sessions, who’s in charge of Trump’s Justice Department, has actively tried to carry out this punitive agenda on drugs. In March, he signed off on a memo that asked federal prosecutors to consider the death penalty for cases “dealing in extremely large quantities of drugs.” And last year, he rescinded an Obama-era memo that asked prosecutors to avoid charges for low-level drug offenders that could trigger lengthy mandatory minimums — a move that effectively told prosecutors to pursue the harshest possible punishments for even low-level drug crimes.

Meanwhile, as Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law, has pursued criminal justice reform, reducing prison sentences for drug offenses has remained out of the question. Instead, Kushner’s efforts have focused on improving conditions in prison and encouraging more rehabilitation programs for inmates.

This all stands in contrast to the bipartisan efforts of the past several years, in which local, state, and federal lawmakers have moved to make the criminal justice system less punitive.

The argument for such reform: More incarceration and longer prison sentences simply have not worked to significantly reduce crime in the US.

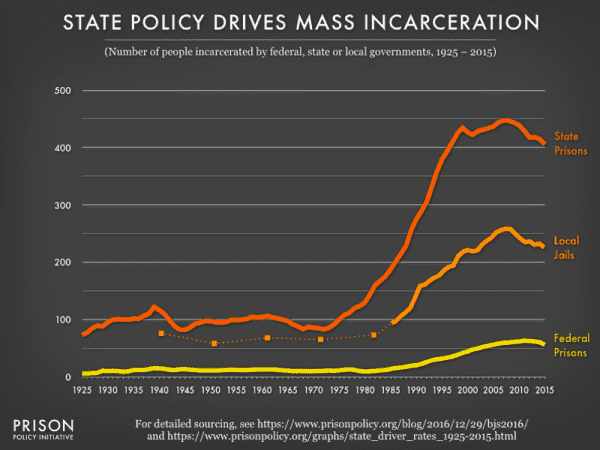

As Mark Kleiman, a drug policy expert at the Marron Institute at New York University, previously told me, “We did the experiment. In 1980, we had about 15,000 people behind bars for drug dealing. And now we have about 450,000 people behind bars for drug dealing. And the prices of all major drugs are down dramatically. So if the question is do longer sentences lead to a higher drug price and therefore less drug consumption, the answer is no.”

One of the best studies backing this is a 2014 review of the research by Peter Reuter at the University of Maryland and Harold Pollack at the University of Chicago. They found that while simply prohibiting drugs to some extent does raise their prices, there’s no good evidence that tougher punishments or harsher supply elimination efforts do a better job of driving down access to drugs and substance misuse than lighter penalties. So increasing the severity of the punishment doesn’t do much, if anything, to slow the flow of drugs.

Broader evaluations have found mass incarceration has only a small effect on crime. A 2015 review of the research by the Brennan Center for Justice estimated that more incarceration explained about 0 to 7 percent of the crime drop since the 1990s, though other researchers estimate it drove 10 to 25 percent of the crime drop since the ’90s.

Another review of the research, published in 2017, led researcher David Roodman at the Open Philanthropy Project to conclude that “tougher sentences hardly deter crime, and that while imprisoning people temporarily stops them from committing crime outside prison walls, it also tends to increase their criminality after release.”

To that last point, the National Institute of Justice declared in 2016, “Research has found evidence that prison can exacerbate, not reduce, recidivism. Prisons themselves may be schools for learning to commit crimes.”

Trump and Sessions, however, have rejected the overall evidence. They argue that tougher prison sentences not only keep dangerous people out of society but also deter others from committing crimes.

So what explains the contradiction? Part of it may be nepotism — Trump has a history of trying to reward people who say nice things about him or are polite to him in-person. But part of it may also be that pardoning and commuting sentences is one of the few areas in which Trump feels actually effective as president, the Post reported:

Besides Johnson’s commutation, Trump has also pardoned political allies, like former Maricopa County, Arizona, Sheriff Joe Arpaio and conservative commentator Dinesh D’Souza, and posthumously pardoned heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson after actor Sylvester Stallone personally lobbied for it. And he’s considering similar actions for former Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich, who’s in prison for corruption, and Martha Stewart; Blagojevich appeared on Trump’s Celebrity Apprentice, and Stewart hosted a spinoff of the same show.

Meanwhile, the people who may be in similar situations with the federal criminal justice system — but don’t have personal ties to Trump — are unlikely to receive any relief from the president.

The federal system locks up a lot of people for drugs

The federal prison system is uniquely punitive when it comes to drugs. Based on the latest federal data, nearly 48 percent of people in the federal prison system are in for drug crimes. In comparison, around 15 percent of inmates in state prisons are in for drug offenses.

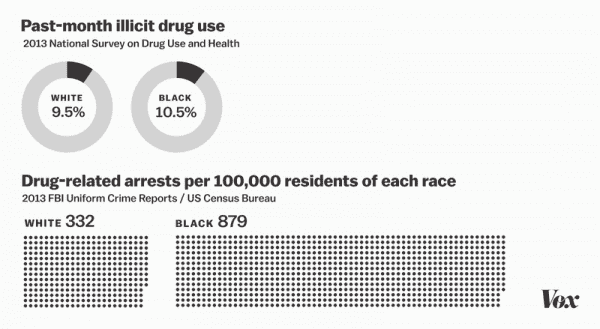

The impact of these sentences is felt disproportionately by people of color. Although black communities aren’t more likely to use or sell drugs, they are much more likely to be arrested and incarcerated for drug offenses. And according to a 2017 report by the US Sentencing Commission, black men got nearly 18 percent longer federal sentences for drug trafficking as similarly situated white men from 2011 to 2016.

Statistics like these and cases like Johnson’s are an easy point of attack for people who want to undo mass incarceration. There are nonviolent offenses, absurdly long sentences, racial disparities, and evidence that the punitive approach doesn’t do much, if anything, to keep the public safe.

At the same time, it’s important to look past the federal prison system and drug offenses if the goal is to truly undo mass incarceration.

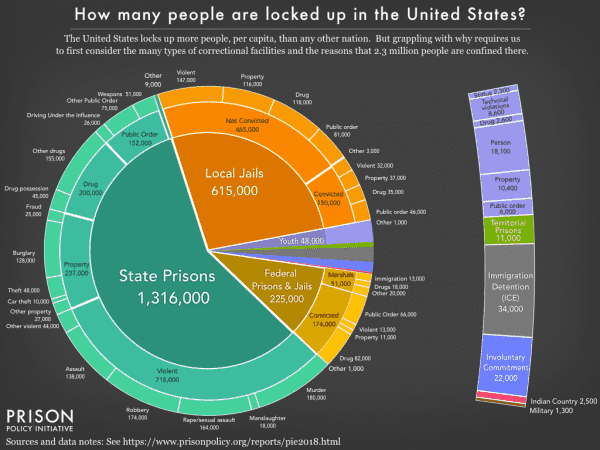

For one, far more people are in prison for violent offenses than drug crimes. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, around 21 percent of people in jail or prison are in there for a drug crime. About 42 percent of people in jail or prison are in there for violent crimes — making violent offenses the biggest driver of incarceration out of all offense categories.

How can this be if so many people are in federal prison for drug offenses? The reality is that the federal system makes up a relatively small slice of the US prison system.

Consider the numbers: According to federal data, 87 percent of US prison inmates are held in state facilities — and most state inmates are in for violent, not drug, crimes. That doesn’t even account for local jails, where hundreds of thousands of people are held on a typical day in America. Just look at this chart from the Prison Policy Initiative, which shows both local jails and state prisons far outpacing the number of people incarcerated in federal prisons:

One way to think about this is what would happen if Trump used his pardon powers to their maximum potential — meaning he pardoned every single person in federal prison right now. That would push down America’s overall incarcerated population from about 2.1 million to about 1.9 million.

That would be a hefty reduction. But it also wouldn’t undo mass incarceration, as the US would still lead all but one country in incarceration: With an incarceration rate of around 593 per 100,000 people, only the small nation of El Salvador would come out ahead — and America would still dwarf the incarceration rates of other developed nations like Canada (114 per 100,000), Germany (78 per 100,000), and Japan (45 per 100,000).

Similarly, almost all police work is done at the local and state level. There are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies in America, only a dozen or so of which are federal agencies.

While the federal government can incentivize states to adopt specific criminal justice policies, studies show that previous efforts, such as the 1994 federal crime law, had little to no impact. By and large, it seems local municipalities and states will only embrace federal incentives on criminal justice issues if they actually want to adopt the policies being encouraged.

Criminal justice reform, then, is going to fall largely to municipalities and states. Many of these jurisdictions are actually way ahead of the federal government when it comes to criminal justice reform, with many passing the kinds of sentencing reforms for low-level offenses that the federal system has struggled to enact. But there’s been little focus at any level on reform for violent offenses.

That’s not to downplay the work of criminal justice reformers. But the effects of such efforts will be limited until lawmakers and advocates look beyond the war on drugs.

Sourse: vox.com