Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

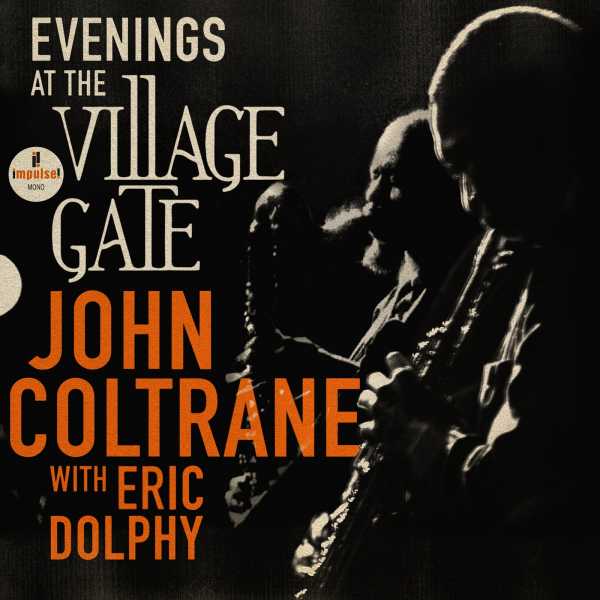

Some rediscovered archival recordings by great musicians are more noteworthy for their news value than for their artistic significance. Others are treasures that extend a view of the artists’ achievements without transforming it; these are more meaningful for connoisseurs than for general listeners. But a newly recovered recording that was released last week, “Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy,” featuring performances taped at a leading New York jazz club in August, 1961, has a singular place in the canons of both headliners. It reveals an entirely new realm of accomplishment for Coltrane and Dolphy, and helps to redefine the very importance of hitherto unreleased recordings.

Rightly understood, the new release (available on CD, vinyl, and digital formats) is as valuable for tyros as for aficionados. I don’t believe in cultural starter sets; with great artists, there’s no point to beginning at a simpler, more conventional stage, or with a sampler. In my experience, what matters is to come in where the passion runs high, and in the Village Gate album, the entire band plays with an astonishing, even overwhelming intensity. The spectrum of achievements that the recording documents for Coltrane and Dolphy is narrow, but it reaches further into the musical future—the musicians’ and that of jazz at large—than any other recordings of theirs from the early sixties that I’ve heard. Here, Coltrane, in particular, offers audacious premonitions of a jazz avant-garde, running years ahead to prefigure the way he’d be playing from 1965 through the end of his life, in 1967.

Coltrane was a late bloomer. Born in 1926, he came to prominence as a sideman, playing tenor saxophone in Miles Davis’s groups, in 1955, and stayed with him, on and off, through 1960. Though Coltrane made many recordings under his own name throughout that time, only in 1960 did he form his own working band, the core of which, heard here, is the pianist McCoy Tyner and the drummer Elvin Jones. (On “Evenings at the Village Gate,” two bassists, Reggie Workman and Art Davis, perform together.) Dolphy, too, had a long musical gestation. Born in 1928 in Los Angeles, he came to New York in 1959, and began to record as a leader in 1960, but worked mainly as a sideman (notably, in Charles Mingus’s group). In the album’s liner notes, Ashley Kahn quotes an interview with Coltrane from soon after this gig: Coltrane said that he and Dolphy had been “talking music for quite a few years, since about 1954.” He added, “A few months ago Eric was in New York, where the group was working, and he felt like playing, wanted to come down and sit in. So I told him to come on down and play, and he did—and turned us all around.”

That turnaround was a revolution, one that’s all the more remarkable for being a revolution within a revolution, because Coltrane was at the center of mighty and epochal change. Coltrane was already at the forefront of jazz modernity. With his sophisticated ideas about harmony and its mighty complexities, he made recordings in the nineteen-fifties that were definitively characterized by the critic Ira Gitler as “sheets of sound,” colossal skeins of notes that ran at high speed, in long-breathing phrases, through ferociously intricate sets of chromatic variations.

Early in 1960, Coltrane was ready to start his own band, but Davis, who had booked a European concert tour, persuaded him to come along. During that tour, Coltrane’s impatience was evident, and he gave it furious musical expression, soloing—usually at much greater length than Davis—with a vehemence that ripped the sheets to shreds. (These concert recordings are among my favorites of Coltrane’s.) In the course of that tour, Davis bought Coltrane a present—a soprano saxophone—and, according to Davis’s drummer at the time, Jimmy Cobb, Coltrane spent most of his time on the tour bus “looking out the window and playing Oriental-sounding scales on soprano.” Later that year, back in New York, Coltrane formed his group. His recording of “My Favorite Things,” which he made on soprano sax, was released in March, 1961, and became, of all things, a jukebox hit. Coltrane built that long-limbed, loping studio performance on the expanded sense of musical space that he had developed with Davis. (That track runs nearly fourteen minutes.)

At the Village Gate, Coltrane inevitably played his hit; a version of “My Favorite Things” is the first track on the newly released album, and the fury of performance blasts the majestic lyricism of the studio version off the turntable. In the studio, Coltrane’s solo is preceded by a pealing, roiling piano solo by Tyner—energetic, grand, but not furious. At the Village Gate, “My Favorite Things” opens with a remarkable solo by Dolphy, on flute, one far wilder than any flute solo he’d yet recorded in the studio. That instrument is resistant to the ardors of the avant-garde, but Dolphy’s six-and-a-half-minute solo makes it wail, stretching its sound by way of exultant leaps, hectic bursts and flurries, repeatedly pounded motifs, sharp-edged fragments of phrases, and notes overblown so hard one can almost hear the metal rippling. As a result, when Coltrane comes in on soprano, he and the band are already near a boil, and he quickly keens, screams, trills with ululating fury, and, in a nine-minute solo, pulls his musical material to pieces.

The drummer Jones’s complex polyrhythms, ever more thunderous in concert, free up the beat, and Coltrane takes that freedom further than he’d done in the studio—his barrages of notes seem to owe little to the divisions of measures and blaze forth to torrential effect without regard to bar lines and note values. The central idea that the newly rediscovered Village Gate recording brings to the fore is the conflict between sense and sound, between familiar musical forms and an utterly individualized mode of expression. Throughout the performances on the album, Coltrane seems obsessed with individual pitches, as if organizing long swaths of music around a single note to which he returns, like a bagpiper providing his own drone-like sound along with the myriad other notes, phrases, and rhythms that it implies. That radiantly, obsessively central home note gives his solos the feel of celestial quests for the absolute, for the all-in-one. His effort to burst through the boundaries of rhythm and harmony and find a totalizing, universal sound has a spiritual, religious dimension—a musical speaking in tongues—that would mark much of his celebrated later work (most famously, “A Love Supreme,” from 1964).

Dolphy, too, had a boldly original, highly intellectualized sense of musical form. He challenged the bounds of tonality with the use of particularly wide intervals, yielding motifs that make his sound instantly recognizable. In the album, he breaks themes and melodies into fragmentary motifs that he elaborates, varies, and transforms. At the Village Gate, in three performances on bass clarinet—an instrument that he made a cornerstone of the avant-garde—he tears his material apart into raw sound by way of buzz-saw growls and high-pitched wails and trills. His energy inspires Coltrane to special heights in a performance of the unlikely tune “Greensleeves” (which Coltrane had recently recorded in a studio big-band session featuring Dolphy’s orchestration). Coltrane, again playing soprano sax, follows Dolphy by entering with a wild explosion of high notes that sounds like a jet engine bursting into the club, and following them with high-speed labyrinthine outbursts. The combination of ecstatic complexity and a folk form conjures, in advance, a musician who hadn’t yet made his mark in the wider musical world, but who would loom large in Coltrane’s and Dolphy’s careers and imaginations, and in jazz over all: Albert Ayler.

Ayler burst onto the New York scene, in 1963, with a roaring and screeching and keening fervor that left behind conventional forms of rhythm and harmony but added the folk elements of spirituals, marches, and blues—and a realm of spirits and ghosts that inhabit those forms. Creating the ne plus ultra of the jazz avant-garde while reclaiming the prehistory that underlay it, Ayler reconceived its place in Black American culture. Coltrane was transformed by Ayler’s music; he invited Ayler to perform with him, adopted some of his most advanced methods, and when dying, of cancer, requested that Ayler play at his funeral. Dolphy (who also performed with Ayler in New York) expanded his own musical forms to reflect Ayler’s influence, too. While on tour in Europe in 1964, Dolphy was reportedly about to join Ayler’s band but, before he could do so, Dolphy died, in West Berlin, of diabetic shock. The Village Gate recordings of Coltrane and Dolphy show that Ayler was no mere singularity who burst meteor-like on the scene; he was the embodiment and avatar of musical ideas and ideals that were already in the air. Far from being solely the record of several great musicians’ bold explorations, the new release exemplifies, in its passionate strivings, the essence of jazz modernity and the spirit of the age. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com