Republicans in Congress just failed to pass a bill that would impose harsher work requirements for federal food stamps as part of the so-called farm bill, but there’s no sign they’re giving up on the idea anytime soon. Their argument is that, particularly with the Great Recession behind us, poorer Americans could and should be doing more to get into the workforce and off federal assistance.

The GOP’s plan raises all sorts of bigger questions, but an alternative plan by Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) asks a pretty straightforward one: Is the problem that people aren’t working enough? Or is it that they don’t receive a high enough wage or generous enough benefits from their employer?

Brown thinks the latter is the real problem, and wants to charge corporations a “freeloader” fee if their employees depend on government aid like food stamps.

His proposal implies that a big overarching problem in America isn’t that poor people aren’t working hard enough; it’s that their wages aren’t high enough, their jobs and hours can be unpredictable, and their employers don’t provide robust enough benefits for them to live without support.

The bill has no chance of becoming law anytime soon. But it still underscores the divide between Democrats and Republicans over the real purpose of social welfare programs. Republicans see a workforce that could be doing more; Democrats see a system where the free market hasn’t done enough to lift up people who have the least.

It’s a crucial argument because right now the GOP, while it holds the reins of power, is undertaking one of the most aggressive crusades for work requirements that we’ve ever seen. It raises a larger question of whether we should government assistance as inherently undesirable. But this Democratic proposal turns on a more narrow issue: Whose fault is it if people can’t afford basic needs and must turn to the government?

Sherrod Brown’s plan to tax corporate “freeloaders,” explained

Brown, who is up for reelection in 2018, actually put forward his plan to tax companies whose workers depend on government programs last fall. He paired it with a plan to offer tax credits to companies that provide more generous benefits. It got a Senate floor vote while the GOP’s tax bill was under consideration and received support from every Senate Democrat.

He has revived the proposal this month, as House Republicans are trying to pass a farm bill that would impose stricter work requirements for the federal food stamps program. The estimated effect of the GOP’s bill is a $20 billion cut to food stamps over the next 10 years, with 1 million or more Americans seeing their benefits reduced or ended.

He discussed the plan during the left-leaning Center for American Progress’s Ideas meeting this week, a showcase for Democrats with presidential ambitions. But it feels especially relevant given the GOP’s farm bill, which failed in the House on Friday but is expected to be revived once conservative infighting over immigration is resolved.

It’s worth noting that Brown’s plan would account for Medicaid, cash welfare, and more, in addition to food stamps. So this is how his “corporate freeloader fee” proposal would work:

- Companies would be fined based on the percentage of their workers who make 200 percent of the federal poverty level or less (about $41,000 for a family of three), a rough approximation of the percentage of workers who rely on some kind of federal assistance.

- The starting point would be a 0.25 percent tax on total payroll for companies with 25 percent or less of workers making an income below that threshold.

- The fee would increase for companies with a higher share of workers: 0.25 percent to 0.5 percent for businesses with 50 percent of workers below the threshold, increasing to a full 1 percent for a business with more than 75 percent of workers making less than 200 percent of the poverty level.

- Companies could reduce their freeloader fee by offering health benefits or by contributing to their workers’ retirement savings

- It would apply only to companies that pay at least $100,000 in payroll every day, thereby exempting many smaller businesses.

It’s debatable whether this is really the right way to encourage companies to pay their workers higher wages and provide more generous benefits. Josh Barro at Business Insider made the case last week that we would be better off simply raising the minimum wage:

Brown might not disagree: Raising wages and increasing worker benefits are the point of his proposal. But his plan is as much a political statement as a policy proposal, arguing that the onus should be on corporations to do better by workers, rather than on workers to do more to earn their benefits.

The data on low-income workers and corporations shows us the real problem

Brown’s proposal exists in a world of increasing income inequality, where the rich are accumulating more and more wealth while incomes of middle- and lower-income Americans fall behind. The tax bill Republicans passed last year, which was centered on a massive corporate tax cut, is expected to only deepen that disparity.

Yet at the same time, the Republican solution for the social welfare programs on which so many Americans depend is to impose work requirements, in the hopes that conditioning a person’s benefits on working or looking for work will result in them being paid more wages and lifting them to a better financial state where they don’t need federal assistance.

But the data we have on low-income workers belies that argument. We don’t have a pandemic of lazy welfare recipients in this country, by and large, but we do seem to have an economy that doesn’t provide many people with enough financial support for basic human needs.

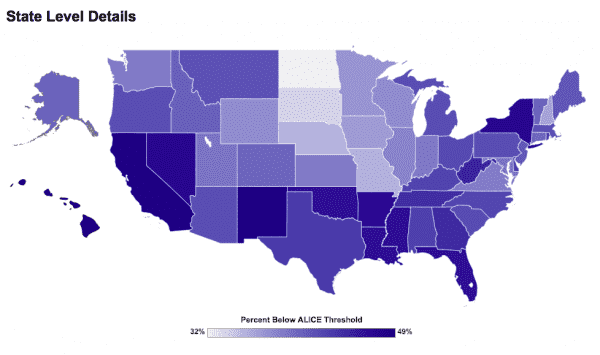

Take a look at this map from the United Way, which attempts to assess how many households in each state don’t make enough money to afford some basic necessities, their so-called ALICE threshold. At least one-third of households in every state qualify, and some states are approaching 50 percent of their residents living in that condition.

As we have covered before with regard to Medicaid work requirements, the problem is not that people aren’t working. Most Medicaid recipients who can work do work. Yet even many of them might fail to meet their state’s new rules at least one month a year — and thus be at risk of losing health coverage — because their hours are irregular or the industry they work in experiences seasonal ebbs. While they might work enough over the course of a full year to meet the requirement, they’ll have months where they’ll miss it.

“The complexity of people’s lives is itself one reason why cutting off Medicaid or other benefits for not meeting harmful work requirements is fraught with problems,” Judy Solomon at the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities told me. “Besides low wages, such jobs often feature instability and periods of joblessness.”

There isn’t one solution to these problems. Raising people’s wages doesn’t mean they won’t need Medicaid if their employer doesn’t offer health coverage. But that cuts to the point of Brown’s proposal. The problem here isn’t that Americans aren’t willing to work; most of the people who rely on federal assistance already do if they can.

The problem is an economy that has rewarded corporations, and by extension the rich people who disproportionately invest in them, more than workers. That is the wrong Brown is trying to right. Whether this proposal is the answer is up for debate. But he is asking the right question.

Sourse: vox.com