“You wouldn’t believe how bad these people are,” President Donald Trump said Wednesday about people who have been deported from the United States, during a discussion about California immigration-law enforcement in the White House. “These aren’t people. These are animals.”

As Vox’s Dara Lind points out, it’s unclear exactly whom Trump was referring to: people deported for being involved in the MS-13 street gang, or anyone who has been deported? In either case, the language is extremely dehumanizing and concerning.

History and psychological science show us that when we refer to people as “animals” or anything other than “people,” it flips a mental switch in our minds. It allows us to deny empathy to other people, makes us feel numb to their pain, and lets us forgive ourselves for causing them harm.

Last year, when Trump gave a speech to a crowd of law enforcement officers on Long Island, he also called MS-13 gang members “animals.”

Related

The dark psychology of dehumanization, explained

This type of language “justifies or even mandates violence,” Nour Kteily, who studies the psychology of dehumanization and its consequences at Northwestern, told me then (check out a feature on Kteily’s work here). He feared it also “communicates that message more broadly to the most fervent of the white supremacists who number among the president’s supporters.”

Just to be clear: Trump’s off-the-cuff remark won’t immediately lead to a worst-case scenario. But it’s worth remembering that dehumanization is already disturbingly prevalent in America. We don’t need anyone — especially Trump — stoking it further. And “dehumanization today [toward certain groups] has been anything but subtle,” Kteily said.

Dehumanization is a mental loophole that allows us to dismiss other people’s feelings and experiences

If you think of murder and torture as universally taboo, then dehumanization of the “other” is a psychological loophole that can justify those acts.

Look back at some of the most tragic episodes in human history and you will find words and images that stripped people of their basic human traits. During the Nazi era, the film The Eternal Jew depicted Jews as rats. During the Rwandan genocide, Hutu officials called Tutsis “cockroaches” that needed to be cleared out.

In the wake of World War II, psychologists wanted to understand how the genocide had happened. In the 1970s, Stanley Milgram’s infamous electroshock experiment showed how quickly people cave to authority. Also in that decade, there was Philip Zimbardo’s “prison experiment,” which showed how easily people in positions of power can abuse others.

At Stanford in 1975, Albert Bandura showed that when participants overhear an experimenter call another study subject “an animal,” they’re more likely to give that subject a painful shock.

From these experiments and others that followed, it became clear that “it’s extremely easy to turn down someone’s ability to see someone else in their full humanity,” Adam Waytz, a psychologist at Northwestern University, told me in 2017.

Dehumanizing sentiment already exists in America. Encouraging it will likely make the country a more hostile place.

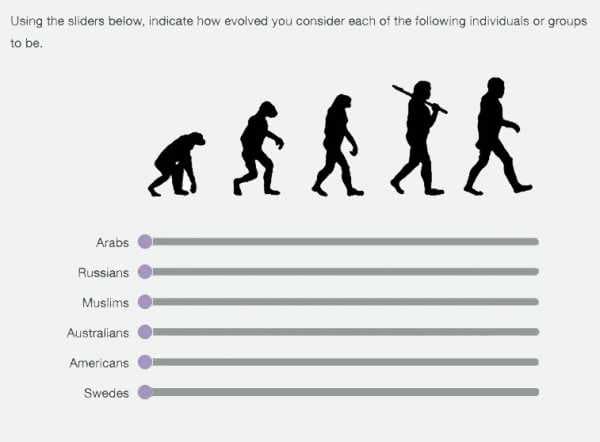

In Kteily’s studies, participants — typically groups of mostly white Americans — are shown this (scientifically inaccurate) image of a human ancestor slowly learning how to stand on two legs and become fully human.

And then they are told to rate members of different groups — such as Muslims, Americans, and Swedes — on how evolved they are on a scale of 0 to 100.

You’d hope people would rate all groups at 100 — perfectly human, right?

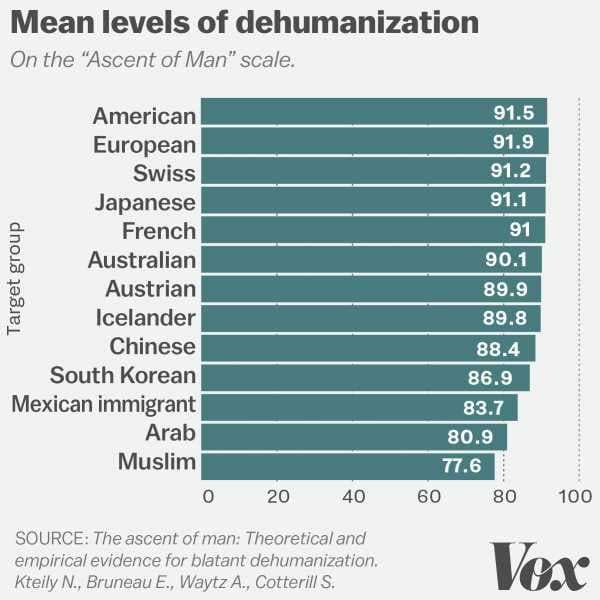

They don’t. Mexican immigrants and Muslims are routinely dehumanized in these studies, scoring, on average, well below 90.

Last year, a psychological survey of the alt-right — an ideological group that supports white nationalism — found even higher levels of dehumanization for many of these groups. On average, the alt-righters in the survey rated Muslims at a 55.4 (again, out of 100), Democrats at 60.4, black people at 64.7, Mexicans at 67.7, journalists at 58.6, Jews at 73, and feminists at 57. These groups appear as subhumans to those taking the survey. And what about white people? They were scored at a noble 91.8.

This is concerning not only because you have one human rating another as “less than” but also because a willingness to dehumanize is correlated with anti-immigrant actions and behaviors.

“Individuals who dehumanized Mexican immigrants to a greater extent were more likely to cast them in threatening terms, withhold sympathy from them, and support measures designed to send and keep them out, such as surveillance, detention, expulsion, and building a wall between the United States and Mexico,” Kteily and a co-author wrote in a 2017 paper.

And that’s only part of the problem.

In his studies, Kteily also looked at what happens when people feel like they’re being dehumanized. And here, the research predicts a vicious cycle.

“Those who dehumanize are more likely to support hostile policies, and those who are dehumanized feel less integrated into society and are more likely to support exactly the type of aggressive responses … that may accentuate existing dehumanizing perceptions,” he wrote in the 2017 paper.

As the vicious cycle intensifies, the whole country becomes a more hostile, less safe place for everyone.

Do Trump’s dehumanizing views trickle down?

The fact that the president, who has enormous power to make life better or worse for immigrant communities, has dehumanizing views is disquieting enough.

But psychological research suggests that Trump’s rhetoric also encourages people who already have prejudicial views to act upon those views.

“I don’t think Trump created new prejudices in people — not that quickly and not that broadly. What he did do is change people’s perceptions about what is okay and what is not okay,” University of Kansas psychologist Chris Crandall said in a 2017 interview.

In 2016, Crandall and his student Mark White asked 400 supporters of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump to rate how normal it is to disparage members of various marginalized groups — like obese people, Muslims, Mexican immigrants, and disabled people — both before the election and in the days after.

After the election, both Clinton and Trump supporters were more likely to report that it was acceptable to discriminate against these groups. For Trump to say the disparaging things he said during the campaign, like that Mexico was sending over rapists — and then be rewarded for it by winning — sent a powerful sign.

“It took away the suppression from the very highly prejudiced people,” Crandall said. “And those are people acting.”

Crandall’s results are preliminary (i.e., not yet published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal), but they’re reflective of the established literature: Exposure to misbehavior simply makes it more acceptable.

A 2017 working paper in NBER looked into this question further. Its authors wondered if Trump’s election acted as a validation of anti-immigrant sentiment. That if someone could become president while stoking xenophobia — building walls, restricting immigration, trumpeting “America First,” etc. — would that make xenophobia more socially acceptable?

And it turns out the answer is yes: More participants in the study became willing to openly donate money to an anti-immigrant organization after the election. (Before the election, too, more participants were more willing to openly donate if they were told Trump’s victory was assured in their state.)

Why we need to be vigilant against dehumanizing language

Inside all of us is the same mental machinery that fueled the atrocities of the past century. “We think others to death and then invent the battle-axe or the ballistic missiles with which to actually kill them,” writes the philosopher Sam Keen.

That’s why we can’t kid ourselves into believing that dehumanizing language is harmless.

Dehumanization and increasing acceptance of prejudice won’t immediately lead to atrocities — but it will make it easier to make life worse for the marginalized.

Sourse: vox.com