Our Agha sprayed chemicals. Every workday, he woke up at five in the morning, put on his rubber boots and TruGreen ChemLawn uniform, and drove out to the wealthiest neighborhoods in greater Sacramento to spray and fertilize lawns. At home, in the evenings, Agha would devour enormous plates of rice and meat, and then he would lie back on the couch with a hot cup of tea, exhausted and aching from twelve hours of handling pesticide tanks. Sometimes my two little brothers and I would sit on the carpet a few feet away and just watch him. It was as if our father was always burning—even then, I had the sense that he was dying for us—but the fires that scorched his body fed our bellies and kept us warm.

Thick-necked, wide-shouldered, and incredibly strong for his size, Agha often said that he was not born for labor (he was a poet, at heart) but that his body seemed to be built to withstand great suffering. He began to work on his farm in Logar at about six years old, cutting wheat and hauling vegetables and chopping branches. Neighbors used to ask Agha’s old father, a widely respected nomad named Hajji Alo, why he worked his little son so hard. “If I don’t teach him how to suffer now,” Hajji Alo had proclaimed, “he won’t learn how to withstand suffering in the future.” Twelve years later, on the jagged cliffs of the Kirana Hills, Agha would remember his father’s proclamation as he spent sixteen-hour days lifting and hauling heaps of gigantic stones. Having fled Soviet Army massacres in Logar, he had arrived in Pakistan, hungry and destitute, with a large family to feed. He felt grateful to his father then. If Agha hadn’t been hardened from childhood, he would never have survived those brutal months in the hills. Agha went on to labor all across the Earth. He crushed stones in Punjab. He built streets in Iran. He repaired machines in Alabama. He fixed pipes in San Francisco. He dragged our little family from one land to the next, keeping us fed and clothed, in search of a job that would finally allow him to settle down and live out his American Dream.

By the time my father landed his job at TruGreen ChemLawn, in 2001, he had developed the sort of work ethic I could only compare to that of Boxer, from George Orwell’s “Animal Farm,” whose signature phrase “I will work harder” carries him through much of the novel. Agha labored all day and almost all night, and even during the weekends he worked in his yard or made repairs to our home or tended to the local Islamic graveyard. Most forms of leisure—video games and movies and television shows—frustrated him to no end. In his youth, he had fought tooth and nail with his old father to attend school, and he was determined not to let me waste my education in America. He used to hand me a book, point out a corner, and order me to sit and read for a few hours. Oddly enough, this was how I developed the strict reading practice that I maintain to this day. I devoured novels, and after a while Agha didn’t have to tell me to sit in my corner. I was already there, reading.

Throughout his life, my father was shot at and bombed. He was beaten close to death by his half brother. His left hand was almost amputated because of infected blisters on his fingers. He was briefly blinded. He broke his arm chopping trees. He buried two murdered siblings, Watak and Gulapa, within a month of each other. He survived an apocalypse in Logar. And yet, of all the calamities that he had suffered in his life, it was a traffic accident, in 2007, that finally brought him to his knees.

On that fateful morning, Agha finished spraying a graveyard in Rancho Murieta in about thirty minutes. It was a seventeen-hundred-dollar project. My father made seven dollars and fifty cents in that same time. The graveyard was supposed to be a ten-hour job, so Agha’s direct supervisor advised him to just sit at the site for the rest of the day. But my Agha—the tragic hero that he is—got antsy after a few minutes and asked for another assignment. While he was driving to the second job, his work van was rear-ended by a big rig. The impact from the crash hurled his body to the side, his shoulder and head smashing into the door. Somehow, he managed to slam on the brakes before passing out. A few moments later, a kind motorist woke him up on the side of the highway. She had called 911. Agha’s work van had suffered very little damage, but his body wasn’t right. He felt dazed and nauseated. He couldn’t comprehend what had happened to him. His supervisor told him to go to the emergency room.

For years afterward, Agha would contemplate this small twist of fate. He had been taught from childhood not to express pain or vulnerability. I once watched him accidentally smash his thumbnail with a hammer and go on nailing a plank of wood while blood dripped from his hand. He tended toward stoicism. But, had he gone to the E.R. as his supervisor had advised, Agha was certain that a regular doctor would have given him a CT scan and diagnosed his brain and spinal injury that day. Instead, almost immediately after the accident, Agha drove back to TruGreen headquarters and visited U.S. HealthWorks, a workers’-compensation medical facility. The doctors there gave him an examination and an MRI but nothing conclusive was determined. A month and a half later, Agha saw a neurologist who diagnosed hi with a brain injury. Over time, however, after a series of conversations with a representative from workers’ compensation, who shadowed Agha during his appointments, the neurologist changed her diagnosis and determined that Agha’s brain trauma was not caused by his work accident. Even so, Agha was given time off through workers’ compensation, with pay, to heal from his injuries.

As the weeks progressed, Agha’s pain only got worse. He felt a stabbing sensation in his neck and shoulders. He suffered near-constant migraines. His arms and hands alternated between numbness and burning. His skull felt as if it was swelling. He lost his sense of smell and his once pristine memory kept faltering. The slightest movement in his neck would send unbearable tremors throughout his body. The pain was so bad that it would make Agha dizzy. Sometimes he would pass out. But, instead of providing my father with proper medical care, his doctors treated him with suspicion and apathy. They grilled him at appointments, twisting his words and subjecting his every claim to an interrogation—or they ignored his concerns altogether. These issues were compounded by language barriers. Though Agha’s English was fairly proficient, he was often confused by medical terminology, especially when asked to describe his pain. He couldn’t understand the exact difference between “throbbing” and “cramping,” between “tiring” and “sickening,” between “unmanageable” and “severe.” He seemed to feel all those words at once. But, even as his pain intensified, his doctors continued to doubt him. Agha’s neurologist suggested that his pain and neurological issues were no longer related to his accident at all. She seemed to imply that he was exaggerating his ailments. Strangely enough, despite her apparent suspicion, the neurologist kept prescribing an expansive list of medications for the remediation of his pain. It got to the point where Agha was ingesting more than twenty different pills a day, including Vicodin and codeine, and because each pill had its own side effect—insomnia, drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, diarrhea, swelling, stiffness, dry mouth, and acid reflux—he wasn’t always certain which of his symptoms stemmed from his injuries and which from the medications. This seemed to further aggravate his doctors. (One neuropsychologist suggested it was chronic-pain syndrome). Within a year, his neurologist determined that Agha was fit for work again, even though this same doctor had written a report recommending that Agha’s driver’s license be revoked. When Agha asserted that his pain was worse than ever and that he couldn’t possibly return to his job, TruGreen ChemLawn cut his workers’-compensation benefits, and our family of eight was left without any source of income.

It was 2008. I had barely started tenth grade and was constantly in trouble. Citations and suspension slips filled my backpack. I argued with teachers, started fights, and always seemed to be on the brink of failing my classes. In fact, I had developed a unique skill for scoring exactly seventy per cent on my exams. So—on top of his constant pain and increasing debt and ongoing medical issues—my father was dealing with an idiot of an eldest son, who he needed to step up and look after his four little siblings but who seemed destined for failure.

With the housing market in shambles, Agha desperately ate into his savings to pay for the mortgage. His neighbors were all losing their homes. As the bills piled up, he went into debt and felt compelled to apply for government assistance. You have to understand. Throughout his life, my father had never felt beholden to anyone. He could grow his own food, hunt his own meat, build his own home, and earn his own money. He took great pride in that sense of self-reliance. Without labor, or the income he accrued from labor, he felt useless. Not only was his mind and body deteriorating but his understanding of himself, his identity as a laborer, was fracturing. He could no longer provide for his family. His daily existence revolved around his suffering, his physical and mental anguish, and yet, he rushed about from hospitals to law offices to courtrooms, repeatedly attempting to prove the very fact of his suffering.

Agha’s only hope was the lawsuit—Kochai v. Nor-Cal Truck & Materials—through which he sought payment for his injuries, medical bills, and loss of earnings. It was an incredibly desperate endeavor. By legally proving the debilitating nature of his pain, perhaps Agha would finally receive proper medical treatment for that same pain. The lawsuit consumed his life, and, to a lesser degree, my own. I read legal and medical documents for my father. I filled out forms and explained test results. I visited offices and courtrooms, hospitals and clinics. I spoke to skeevy lawyers with so many folders and cases piled up on their desks, I wondered when they would ever have time for my father. I testified before old white judges who got to sit up on their thrones, in their fancy costumes, and look down upon my father and determine whether his pain was real. Everywhere I went, I felt as if I had to beg some little god to have mercy on my family. I began to hate this country and its myriad of systems and courtrooms and departments, which existed, it seemed, solely to exploit or ignore the most overworked and underprivileged members of our society.

“Labor is invisible,” a professor once told me, years later. He pointed out the window of our classroom, toward the green quad. “You see those clipped trees. That perfectly cut lawn. You walk past them every day. But who shapes the trees? Who cuts the lawn? And why do you never see them? Everywhere you go, you are surrounded by the products of labor. Every clean sidewalk, every polished hallway, every blade of cut grass. Our world cannot function without them, and yet the laborer remains unseen and unheard. Why is that? What is it about our national culture, or our economic structures, that necessitates this invisibility? Why is it that America turns its laborers into spectres?”

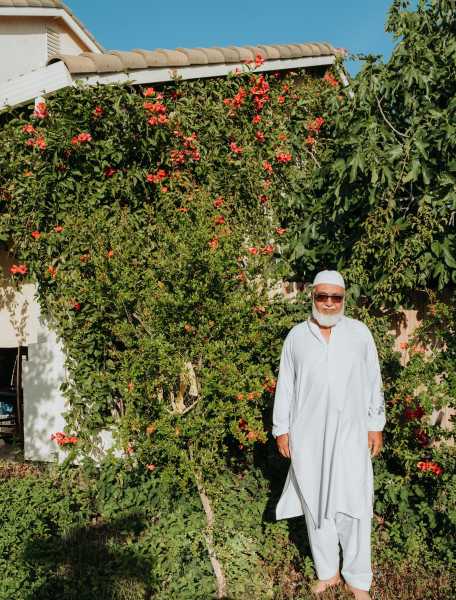

Photograph by Jalil Jan Kochai

I thought of my father waking before dawn, driving hours through the cool morning mist, to cut grass, to spray and inhale chemicals—to become a spectre. He had done everything right. He worked like an animal for his employers. He had no criminal record. His credit was great. He didn’t drink or do drugs. He went quietly to work every morning and came quietly home every evening. He obeyed his bosses and won employee of the year multiple times. He paid his taxes and mowed his lawn and met with his children’s teachers. He was the ideal immigrant. The American Dream personified. And yet, the moment his broken body could no longer be exploited for its labor, he was doubted and ignored and humiliated. Everywhere he turned for help—workers’ compensation or welfare or Social Security or Medi-Cal or the court system itself—he was treated like a scam artist. A crook. The bureaucracy inherent to these programs turned him into a stack of documents. A list of ailments. He was dismissed and forgotten. Just another spectre in America.

In those days, I felt helpless all the time.

Once, when our food assistance was cut because of an administrative error, I went to visit the local CalFresh office for help. Barely seventeen at the time, I didn’t exactly understand how bureaucracies functioned. I walked in, took a numbered slip, and waited my turn. When my number was called, I entered the office of a welfare representative and sat down in a chair in front of her desk.

The first thing she said to me was “Why did you sit down?”

I was confused. I thought I had entered the wrong office.

“Why did you sit down?” she asked again. “Did I tell you to sit down?”

“No,” I said and apologized.

“It’s not O.K.,” she replied.

And so, slowly, pathetically, I pushed out the chair, stood up, and waited for her to give me permission to sit back down.

Instead, she just watched me stand there for a bit.

It couldn’t have been more than ten or fifteen seconds, but it was so humiliating, I began to shake. I wanted to kick in her desk and smash her computer. I wanted to punch the wall until my fists bled. I felt tears welling up in my eyes.

Finally, she told me to sit down and give her my number. I was so upset, I forgot which document I needed to provide her, and she became frustrated and asked why I had come unprepared. I apologized again and hated myself for it. But I couldn’t return home having fucked up another trivial task. A few minutes later, she pulled up our case, typed a few things into her computer, and the issue was resolved. I asked for permission to leave, and she granted it.

Once, in the middle of the night, Agha’s nerve pain got so bad that he asked me to drive him to the emergency room. Usually, even at his worst, my father suffered his bouts of nerve damage in silence so I knew his pain must have been unbearable.

In the emergency waiting room, Agha clutched his head with both hands, sweat trickling down his scalp and neck, soaking his shirt. He was trembling. Eventually, a nurse called his name and asked him where he felt the most pain.

“In my neck,” he said, “and in my shoulder and down my arm and in the right temple of my head.”

“And how does it hurt?” she asked.

“The wreck,” he said, “the wreck.”

“No, Agha,” I interrupted in Pashto, “she means what does the pain feel like? Can you describe it to her?

“It burns and then it—” he clenched and unclenched his fist.

“It pulses?” I asked.

“Yes, it pulses. But it is like a stabbing, and in my hands a prickly—how do you say it? When your skin is like cotton?”

“It’s numb?”

“Yes, it’s numb,” he said and sighed deeply, “but then the burning of it washes over me.”

The nurse (bless her) immediately admitted us.

While he waited for the doctor to arrive, Agha lay in the hospital bed, writhing and sweating and scraping at his right arm and neck. He pressed his fingers into the sides of his skull as if to pierce his own brain. A few feet away, I paced back and forth, not knowing what to do or say. When he began to wheeze, I panicked and rushed out into the hall and begged for help. A nurse followed me into the room where we found my father laying on his side, away from the door, with his face in his hands. He wheezed and muttered the name of God (most merciful is He) over and over until a doctor arrived and provided a strong shot of pain medication.

I sat with Agha late into the night, watching him sleep, as he, no doubt, had watched me sleep on countless nights in hospitals all over the world, and he looked so peaceful in his dreams, I thought of locking the door and letting my father sleep through the night and day, and perhaps the next night, too. I thought of Boxer and the slaughterhouse. I thought of all the fires—bombs and mines and missiles and torches—my father had escaped in his youth, only for him to be devoured by the fires lining his nerves, beneath his skin, all throughout his beleaguered body.

Over the years, my father figured out a medication, physical therapy, and injection routine that allowed him to manage his pain. He had surgery on his injured shoulder in 2009 (two years too late), which helped with some of the most severe nerve damage. Nor-Cal Trucks ended up settling with Agha, and our family received a one-time lump sum of two hundred and fifty thousand dollars, more than half of which went to lawyers and doctors—including the neurologist who had denied Agha’s pain in the first place—ten thousand to pay off old debts, and the remaining ninety thousand went into our mortgage. If nothing else, my father no longer feared losing his home to the bank.

Still, his injuries lingered.

He would have a good week, just moderate pain in his back and shoulder, only for the nerve damage to sneak up and lay him out for a couple of hours—or days. It was random and vicious. It got to the point where I could walk into the house and look at my father’s face and see the aching etched there beneath his eyes, on his scalp, in the creases of his mouth. He would get sweaty and dazed and his eyes would turn glassy, and he wouldn’t be in the room with us, for a while, he would be someplace else, inside the pain, just trying to breathe.

“Despite everything,” my father once told me, years after the accident. “I consider myself a lucky man. I’ve heard the sound of bullets flying past my head. I married an incredible woman I’d never met in my life. I journeyed to a country without knowing its language or custom or law. It ate me up and tried to crush me. And yet, here I am, with all of you, still going.

He won’t stop. The old man. We’ve all told him—his doctors, his children, his wife—to slow down, to go easy with his body, but, even now, I’ll catch him awake before dawn, out in his little yard, squatted and hunched over, tending to his garden as if he’s still a farmer in Logar, as if his body isn’t battered and bruised and torn to shreds, as if his nerve pain won’t act up at any moment, as if the labor is all there is.

“What else can I do,” my father tells me when I chastise him.

Sometimes I wonder if he also means: “What else can I be?”

I imagine him at six years old, a little farmer, lying beside his brother Watak on a toshak warmed by their bodies, their sleepy farts. Maybe he’s drooling a bit, maybe it’s just starting to snow outside, maybe he’s on the edge of a dream, something silly, or joyous, until he hears his old father calling his name, and I wonder if, back then, he would cling to the dream for a bit, just a few more seconds, before rising up and storming out into the cold world. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com