The photographs that Tina Barney calls “The Beginning” (which form the basis of a show at the Kasmin gallery through April 22nd) are set in a marina and on a golf course, in private pools and on broad summer lawns, on Rodeo Drive and Fifth Avenue. But, despite the privileged environs, the mood is anxious and vaguely uncomfortable, as if Barney were searching not just for her best vantage point but for her place in a world that she was born into. A descendant of one of the Lehman brothers, she grew up on the Upper East Side, where she was embarrassed to be driven to school in a chauffeured Cadillac. “I so deeply understood the perfection of my life,” she writes in a brief forward to a new book from Radius, also titled “The Beginning,” that collects this early work. “The splendor of the landscape, the houses and their interiors, and the people I cared for more than words can say.” But, whenever she tried to capture her milieu on film, everything she knew and loved about it seemed to slip away. Only when she realized she could get closer to the truth by staging it—by subtly combining fact and fiction—did her pictures really come together.

“Beach Club Pool,” 1980.

“Golf Lesson,” 1980.

“Award Ceremony,” 1980.

Barney’s 1997 book, “Theater of Manners,” and the exhibitions that preceded it, were breakthroughs. Suddenly, she was in the avant-garde alongside a group of photographers—including Gregory Crewdson, Jeff Wall, Annie Leibovitz, Larry Sultan, and Philip-Lorca diCorcia—who approached their medium like filmmakers. The directorial mode wasn’t exactly new. Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton had been turning their fashion sittings into extended narratives for decades. But the photographers from in and out of the fashion world that MoMA brought together for the 2004 show “Fashioning Fiction” made it clear that even a single frame could contain a compressed story, with startling impact and sustaining aftereffects. Because Barney’s work was so clearly autobiographical (she sometimes appeared in the pictures) and brought up issues around class, money, family, and, not so incidentally, whiteness, Barney was among the most intriguing and engaging of this new group.

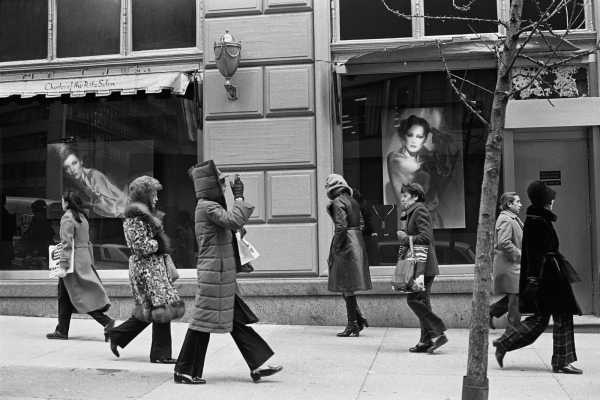

“Women on Fifth,” 1976.

“Judith Smoking,” 1977.

“Girl Lifeguard,” 1977.

Barney’s “Beginning” work is a prelude to all that. It was made between 1976 and 1980, when Barney was in her early thirties, married, with two sons, and shuttling between the East Coast and her family in Sun Valley, Idaho. Although several pictures from the time made it into her “Theater of Manners” collection, most had never been printed or exhibited. Barney describes them as “loose sketches a painter might use to plan for a larger painting,” and their most obvious influence is the calculatedly careless snapshot aesthetic of Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, two photographers she mentions in her forward as “masters of the unaltered photograph.” But Barney is too exacting to be casual, and many of her attempts at vernacular naturalism feel stiff or self-conscious. The pressure to be spontaneous only stifles her, leaving her so outside the frame that you wonder why she’s even there. The picture of a line of unhappy-looking bathers at a fogged-in water park that wraps around the cover of the “Beginning” volume could have been taken by a drone.

“Waterslide in Fog,” 1979.

“The Guest Room,” 1979.

“The Art Gallery,” 1980.

“Amy, Phil, and Brian,” 1980.

Even when Barney’s clearly in her element—at a garden party, an art gallery, or with a woman primping in a wallpapered guest room—she doesn’t know where to stand or what she really wants to look at. In hindsight, she can locate the problem. “In the beginning, I would have never dared direct someone that I was photographing,” she writes. When she tried, asking one of her young sons and two friends to stand at three spots around a backyard pool in Bel Air, the result was stilted, as she points out: “I imagined something else, something more fluid.” Still, she includes that picture in the exhibition and at the end of the book, and it’s one of the few early images to show up in “Theater of Manners.” Its failure apparently haunted her, but it didn’t keep her from continuing to explore the possibilities of staged photography—or what she calls “directing.” But, the more Barney looked, the more conscious she was of how rarely the people she grew up with touched or connected in any way. “I thought family members didn’t show enough physical and emotional affection towards each other,” she writes. If the only way to picture or bridge that disconnect was to gather people together for a photograph, she’d find a way to do that.

Barney’s introductory text in “Theater of Manners” is remarkably revealing. Even after she’d worked up the courage to arrange family and friends for her pictures, she writes, she still felt that she was “invading a privacy that every family holds within itself.” Growing up, she was never allowed in her parents’ quarters, she explains, and “to go into the living-room was almost a daring thing to do, like I was crossing some kind of ‘out-of-limits’ border.” When even casual intimacy is seen as transgressive, insisting that people come together for pictures was a form of rebellion. Barney writes, in one of a series of undated diary entries, “I want to get inside, because it’s the only thing that’s worthwhile. . . . I want to know what other people feel. Otherwise it’s too lonely.” In today’s photography world, when conceptual strategies and random sightseeing rule, Barney’s only-connect sincerity could not be less fashionable or more valuable, and it sets her apart. Her work can be both sharp and affectionate, but she’s neither a satirist nor an apologist. In recent years, she’s moved on from photographing family and friends, and her work, in editorial spreads and elsewhere, has grown less personal and more illustrative. With “Beginnings,” she’s regrouping and going back to her roots, as if to remember where she started and how far she’s come. Even if the old work suggests no obvious ways forward, it’s a reminder of what made Barney matter once she’d found her point of view.

“The Cowboy Boots,” 1976.

Sourse: newyorker.com