S. S. Rajamouli was born in 1973, in the South Indian state of Karnataka, to a family from a dominant caste. He learned how to make movies from various odd jobs and apprenticeships, including a years-long stint working for his father, the successful screenwriter Koduri Viswa Vijayendra Prasad. In the past two decades, Rajamouli has earned a reputation among Indian moviegoers for a series of formally ambitious blockbusters, including the spectacular “Baahubali: The Beginning,” from 2015, which inspired a new wave of Indian historic epics. But he has found a new level of global success with his latest film, the joyously over-the-top action-fantasy “RRR”—short for “Rise Roar Revolt”—which is among the highest-grossing Indian movies of all time.

“RRR” was first released last March but caught on with American viewers over the summer, after an unusual U.S.-wide theatrical rerelease organized by the distributor Variance Films and the film consultant Josh Hurtado. The movie hasn’t left U.S. theatres since. A Hindi-dubbed version on Netflix has furthered its word-of-mouth reputation. For many American viewers, “RRR” has provided an introduction not only to Indian cinema but to the Telugu-language film industry sometimes referred to as Tollywood, which operates separately from its more famous Hindi-language counterpart, Bollywood. In January, Rajamouli won Best Director at the New York Film Critics Circle Awards. His film is nominated for an Oscar in the category of Best Original Song, for the international viral hit “Naatu Naatu.”

Set in pre-independence Delhi during the nineteen-twenties, “RRR” follows two characters loosely based on the real-life Telugu revolutionary leaders Komaram Bheem (N. T. Rama Rao, Jr.) and Alluri Sitarama Raju (Ram Charan), as they team up to challenge a host of ruthless British officials. Bheem and Raju exhibit superhuman abilities in the realms of fighting, taming tigers, and conducting spontaneous dance-offs. For many American viewers, their story will come across as an exuberant anti-colonialist tall tale. But some Indian critics have identified a strain of Hindu nationalism in the film’s mythologized telling of Bheem and Raju’s historic freedom fight. They point to the fact that Raju, who belongs to a privileged caste, is ultimately elevated in the narrative above Bheem, a leader of the Gond tribe, who declares himself a humble student of Raju’s teachings. They point to how this story line replicates hierarchical relationships from the Hindu epics the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, which Rajamouli has cited as sources of inspiration, and especially to the film’s patriotic final number, “Etthara Jenda” (“Raise the Flag”), which celebrates certain historic figures favored by the Hindutva movement while leaving out founding fathers such as Mahatma Gandhi. In Vox, the critic Ritesh Babu called the movie a “casteist Hindu wash of history and the independence struggle.”

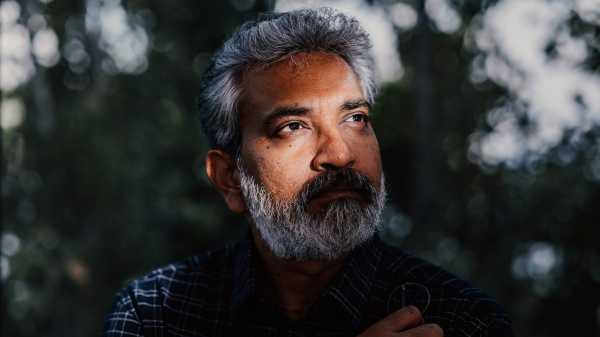

There are other reasons to wonder about the movie’s political intentions. Rajamouli’s father, who co-wrote “RRR,” has been at work on a film commissioned by the R.S.S., the Hindu-nationalist extremist group, which he has called a “great organization.” Rajamouli told me that his father’s script is “very emotional and extremely good.” But, during several recent interviews over Zoom, Rajamouli denied that “RRR” had any deliberate ideological implications and was persistently evasive on the subject of the country’s politics and his own. “Entertainment is what I provide,” he said. Rajamouli is forty-nine years old, with a swoop of salt-and-pepper curls and a thick beard in a matching shade. (You can spot him in a cameo during “RRR” ’s patriotic finale.) In our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, he also discussed atheism, what makes a good action sequence, and some of his creative influences, including Mel Gibson and Ayn Rand.

When did you know that “RRR” was a crossover hit?

We started seeing a positive response on social media first, which continued with tweets from celebrities praising the film. Then the movie was released on Netflix, where it topped the charts. Then it opened in Japan and started doing well there. So we only gradually saw that the response was greater than what we envisioned. There was a screening in L.A., at the TCL Chinese Theatre IMAX, where ninety per cent of the audience were Americans. They reacted in the same way as the audience back in India when the film was initially released: jumping, clapping, standing up, and dancing in the aisles. When that happened, we thought, O.K., whatever we’ve been hearing on social media, we’re now directly seeing with our own eyes. We did it.

I spoke to the film programmer and consultant Josh Hurtado for the Times last year about the film’s rerelease in American theatres. He said that the things that won audiences over were the same things that had originally deterred them from watching Indian films, specifically “long run times, song and dance numbers, and ridiculous action.” Does that response surprise you?

Not really. I also don’t disagree with Westerners’ complaints about the songs in Indian films. There are many times where the songs can hamper the film’s narration. But, after working with songs for so long, some Indian filmmakers came to understand the power of song and dance, if it makes the story go forward, rather than stopping the story. Very few Indian filmmakers have figured out how to do that, but when that happens even Westerners will enjoy it.

As for action set pieces, we, as human beings, like to see fantastic things happen. But, if action is not substantiated properly, then it becomes ridiculous. If it is substantiated, and if I make the audience feel that the characters in the film need to do something extraordinary, audiences will applaud.

Is audience feedback something that you actively seek out?

I do that a lot, yeah. Because, essentially, a film works if the director or the filmmaker is thinking along the same lines as the audience. If not, then the film won’t be successful. For me, it is very important to understand how my audience members feel about my films. At the same time, I don’t think many people can really express how they like or dislike the movie. The moment you put them in a position to judge your film, they lose that perception. The best way for me to judge my own films is to go to the theatre, sit with the audience, and feel how they’re responding. I visit theatres showing my films sometimes ten, thirty, forty, or even a hundred times to get a sense of how the audience receives my films.

Have you been surprised by audience responses to particular scenes or moments from “RRR”?

One example: during the climax, when Raju gives a speech about a bullet, he repeats the same words that Scott said earlier in the movie, and tells Bheem to give the bullet back to Scott—meaning, to shoot him down. The response to this scene, across America, was much stronger than what it was in India.

What do you make of that difference?

Probably because Indian audiences expect big action scenes after having seen my previous films. They’ve seen those movies and are now looking forward to big action set pieces. American audiences are looking with fresh eyes.

You’ve previously said that you don’t like the term “Tollywood” and prefer that your movies be described as South Indian or Telugu-language movies. Is that because of the association with Bollywood or even Hollywood films?

There is no sense in it. See, there is a reason why Hollywood is called Hollywood, right? Because there’s a place called Hollywood, where most of the films are made. There is no reason why a Hindi film is called Bollywood, or a Telugu film is called Tollywood. These terms make the films they’re describing sound like cheap imitations.

In earlier interviews, you’ve cited both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata as major influences on all of your films. How so?

I’ve read these stories since I was a child, and in the beginning they were just nice, engaging stories. As I started growing up, I read different versions of the text, and the story started evolving into something much bigger for me. I could see the characters, the conflicts within the characters, and their motivating emotions. And I started understanding and loving these texts even more. Anything that comes out of me is somehow influenced by these texts. Those texts are like oceans: every time I visit them, I find something new.

In terms of cinematic touchstones, you seem strongly influenced by “Mayabazar,” the 1957 mythic-fantasy film. You even included archival footage of that movie and its star, N. T. Rama Rao, Sr., in your movie “Yamadonga.” Are there scenes, performances, or qualities to “Mayabazar” that inspire you?

Many. For instance, the language that is spoken in “Mayabazar” is supposed to be from the Mahabharata. The many dramas and films that came before, and many films that came after, use a very bookish language for the characters, because they’re supposed to be either gods or ancient people. In English, it would probably resemble a Shakespearean kind of language. But in “Mayabazar,” the language that the characters speak is a very present-day, modern Telugu language. I was quite surprised the director had the guts to do that. There are also several instances in the film where they use words that are not Telugu. They just invented words for comedic effect. That’s quite daring when your film’s story is taken from a classic text like the Mahabharata. “Mayabazar” features almost all of the stars in the Telugu film industry from that period, and they experimented so much. That was a big inspiration for me when I made “RRR,” a completely fictionalized story featuring characters based on real people. My confidence to make “RRR” comes from “Mayabazar.”

I haven’t really seen you talk much about Mel Gibson as a filmmaker. The films “Braveheart” and “Apocalypto”—specifically their action scenes—were clearly influential for you. But I was curious if you could talk about “The Passion of the Christ.” How did it affect you when you saw it, and what did you take away from it?

Actually, I didn’t like “Passion of the Christ.” It was too violent for me, at least at that point in time. I couldn’t watch the film in one sitting. I watched a little, shut it off, waited two or three days, watched a little more. There are some moments that are great, definitely. But, on the whole, not a fan. [Laughs.] The climax of “Braveheart,” not “Passion of the Christ,” was the inspiration for Bheem’s song in “RRR,” in the scene where he’s being whipped [by Raju, acting on orders from the British].

What in particular about “Braveheart” inspired you?

I usually don’t like sad endings. Any story that I read, any film that I watch, I don’t like it when the hero dies. But I remember the end of “Braveheart,” when we can see the hero [Scottish freedom fighter William Wallace] being tortured and eventually killed. He shouts “Freedom,” and when the film ended I didn’t feel sad. I felt very emotional. I felt my spirit being uplifted. You can see the pain in his face, how he calls on his inner strength to say what he wanted to say, even though it is just one single word. That made a deep impact on me.

Later, when I wrote “RRR,” I wanted to show a shift in the tone of Bheem’s character. He’s an innocent person until this moment. Then he takes a hard stance against his oppressors. We thought that we had a hard emotional foundation for an action sequence and didn’t want to waste a chance. But then we thought a song would be nice. That’s how people in Telangana, the region where Bheem’s from, express their emotions. And I remembered “Braveheart.”

You’re an atheist, which is a little surprising given how much of your drama focusses on spirituality and faith. Do you consciously separate your personal beliefs from your movies, for the sake of making better drama or reaching a wider audience?

Absolutely, yes, I keep them completely separate. There might be some overlap, but I don’t try to bring my personal beliefs into my films. For me, there is a very clear and pure relationship between me and the audience. The audience is paying me their hard-earned money, giving me their time, and expecting some kind of entertainment. That’s my job.

Do you remember when you first identified as an atheist?

We have a giant family, and everyone—my father and mother, cousins and aunts, and everyone else—is deeply religious. I remember, as a young kid, I had doubts after reading stories about the Hindu gods. I used to think, This doesn’t seem real. Then I got caught up in my family’s religious fervor. I started reading religious texts, going on pilgrimages, wearing saffron cloth, and living like a sannyasi [ascetic] for a few years. Then I caught onto Christianity, thanks to some friends. I’d read the Bible, go to church, all kinds of stuff. Gradually, all these things somehow made me feel that religion is essentially a kind of exploitation. I worked under a cousin of mine [the Telugu writer Gunnam Gangaraju] for a few months. He introduced me to Ayn Rand’s “The Fountainhead” and “Atlas Shrugged.” I read those novels and was greatly inspired by them. I didn’t understand a lot of her philosophy, but I understood the basics of it. It was around that time that I slowly started moving away from religion. Even at that time, my love for stories like the Mahabharata or the Ramayana never diminished. I did start pushing away from those texts’ religious aspects, but what stayed with me was the complexity and the greatness of their drama and storytelling.

Considering the importance of religion in your family, what do your family members think about your atheism?

They feel very sad for me, because I am going away from the path of religion. I don’t say bad things about God, I never do that. I respect people’s feelings because I know a lot of people depend on God a lot. Still, my father used to get angry when I used to say that I don’t believe in religious rituals or that kind of stuff. Now he’s made peace with it and respects my way of life.

Can you say more about how Ayn Rand inspired you?

Her narration made a deep impact on me—the way it enhances her characters and takes readers through their struggles, her visual style of narrating events. That made a big impact on me, as a filmmaker. I understand parts of her philosophy, but that goes over my head once she gets into it. I’m not such a deep thinker, I’m more of a dramatic thinker, so I like the drama part of it.

Both “Atlas Shrugged” and “The Fountainhead” feature titanic characters whose accomplishments reflect their superior will power, among other qualities. Is that sort of transcendent capability, to go beyond one’s class and other social limitations, something that you admire about Rand’s protagonists?

Yeah. Rand’s protagonists are strong and believe in their philosophies and are willing to go to any lengths to fight against society and live the lives that they’ve envisioned for themselves. And, in both of the novels, even though the heroes’ philosophy is the same, their execution of it is completely different. Howard Roark doesn’t care about society. He doesn’t care about anything else. He just believes in his philosophy and way of life. John Galt subscribes to the same ideas, but he wants to change society. He wants to fight against the system and to see the right thing happen. That’s the main difference between the two protagonists, and I love them equally because of their determination to achieve their goals.

Can you talk a little bit about your understanding of the caste system in India growing up?

I was lucky enough to be born in a family where all my uncles and my father really hated the caste system. It was never discussed in the family. Until I went to college, I didn’t know which caste I belonged to. My father came to my college to fill out the forms, and there was a column where he had to indicate his caste. My father refused to fill out the form. He had a big argument with the clerk: “Why should I fill in the caste column? I don’t belong to any caste!” The clerk was a small guy, and he said, “Sir, I don’t know all that. I just know that you have to fill a column before I can accept the application.” That was the first time that I learned that there is something called caste and that I belonged to a certain caste.

To be frank, I was never a firsthand witness to the evils of the caste system. All my knowledge is from others, from books, stories, the epics. It slowly dawned upon me that many sugarcoated truths were not actually true, and that groups of people were really tormented because of the caste system. It was several revelations from reading on different topics, speaking to different friends, and putting two and two together about things we try not to discuss.

You’ve worked with your father, the screenwriter Koduri Viswa Vijayendra Prasad, for decades. What would you say about your respective approaches?

We like similar movies, we cry and laugh at similar scenes—so we are quite in synch with each other. If there are different actions that a character can take, we argue about the pros and cons of those actions. I might say that the hero taking this route will give me a better action sequence or romance and comedy. And he might say a different approach. Our arguments are about those finer nuances, but we are never in disagreement about basic story structure, characterizations.

You didn’t study film but rather got your first filmmaking experience as a screenwriter. What can you tell us about that early hands-on education?

I was a college dropout and was basically doing nothing at home. My father was worried that I was wasting my time, and he constantly said to me, “What do you want to do with your life? You can’t idle your time away.” So, to escape from my father’s wrath and constant questioning, I said, “I want to become a director.” I had absolutely no idea what a director does, let alone what qualifications you need to become one. But my father took that seriously and said, “There are thousands of aspirants out there who want to become directors, so, if you want to become a director, you should have some skill set.”

He spoke to some people and put me in touch with the film editor Kotagiri Venkateswara Rao. I think I was his tenth or eleventh assistant. My job, at that time, was to stick labels onto the film cannisters. I was not even allowed to touch the reels because the film itself was too precious. I didn’t think much of it at that time, but I started observing the directors who would come to edit. I also observed the editors, stunt choreographers, and dance choreographers who came to edit their films. They would discuss, during their break time, the flow of their films. More than editing, I learned about dramatic essentials, like when you should put a song or a fight in a film.

How long did you do that?

I worked there for six or seven months. Then I went and joined a recording studio where the background score was done, the spools were loaded, and the film reels were marked from the beginning to the end of musical pieces. My job was to assist the person who does all that. Again, I wouldn’t say I learned much on that job, but I observed film directors and music directors discussing what kind of music should be used in any given scene and why. Those conversations were very, very interesting to me.

My father was a story writer at the time, and he used to discuss stories with all the kids in our family. And we had thirteen cousins at that time. We used to live together in one small house in Chennai. I would sometimes disagree with my father, telling him that an action piece would look better this way, or a dramatic piece would look better that way. I used to give my input and my father slowly realized that I had a knack for the dramatics of film writing, so he started encouraging me to do more and more writing.

I also worked as an assistant director to [the film director] Mr. Kranthi Kumar. I didn’t learn much about direction, but I did observe the different complications that a film director runs into. Later on, my early work experiences helped me to pull all the pieces together. But, at that time, I understood that a director’s job is more of a manager’s job than a creator’s job. They bring all the departments together and get them to work in a certain way. My dad asked me to assist him after I worked on two films with Kumar. “You can do better,” my father said. “You can learn more, and you’ll help me more by working as an assistant with me.”

What were your first impressions of your father’s scripts or story outlines?

I mean, because I learned the dramatics of screenwriting from my father, I thought all of his ideas were great. Obviously, they weren’t. They were sometimes lacking. But at the time I was so starry-eyed about my father, who was also my boss, that I thought whatever he did was great. When I worked under him, my job was predominantly to create action set pieces. He had many other assistants, too, and all of us developed dramatic scenes that led to an action sequence. I was interested in the job of figuring out action sequences. At that time, story writers didn’t usually write the details for action sequences, but my father’s specialty was that he also wrote those details. So that became my job, too.

How would you describe the role of watching films in your house growing up? Was it a family activity, or strictly between you and your dad?

It was a family activity. All of our cousins and uncles were film enthusiasts. And not just films—we discussed epic stories, music, novels, authors, and poetry. We talked about art a lot in the family, but it was predominantly about films, film poetry, film stories, film language.

You’re a big fan of “City Lights.” Was that your first Charlie Chaplin movie?

I went to high school and college in a town called Eluru. At the time, I still had no ambitions to be a director. I was still a kid. “City Lights” was the only Chaplin film that I saw. I was so naïve. I thought all English-language films were action films, because only certain films were brought up to that part of the country, and most of them were action films. So I thought I was going to see an action film. It started as a mooki, or a silent, often black-and-white film, and didn’t look like it was going to have any kind of action. So I was quite disappointed for the first few minutes. Then I became engrossed by the story of “City Lights.” It’s one of my favorite films.

A number of critics have read into the nationalism in both the pan-Indian style and presentation of not only “RRR” but also your two “Baahubali” films. You’ve previously said that you understand those interpretations but that your critics are “just being blind.” Can you elaborate on that a little?

It’s very difficult to generalize, because there are people who find objections with different sections of my films. But, if you pick out one point that they have, then I can elaborate on that.

There’s often suspicion of how your historic characters are portrayed as representatives of an idealized past, even an ethnically uniform sort of past, which ignores current tension with, for example, the B.J.P., the R.S.S., or other anti-Muslim groups. They suspect that your films are your way of rewriting the past for nostalgia’s sake. Does that surprise you?

First of all, everyone knows the “Baahubali” movies are fictional, so there is nothing for me to say about whether it is a distortion of history to portray historic characters to suit the present B.J.P.’s agenda. As for “RRR,” this is not a documentary. This is not a historical lesson. It’s a fictional take on characters, which has been done many times in the past. We also just talked about “Mayabazar”—if “RRR” is a distortion of history, “Mayabazar” is a distortion of the historic epic.

I’d also like to point out one more thing to people who accuse me of supporting the B.J.P. or the B.J.P.’s agenda: when we first released an early character design of Bheem, I showed him wearing a Muslim skullcap [to disguise himself]. After that, a B.J.P. leader threatened to burn down theatres showing “RRR,” and said he would beat me in the road if we didn’t remove the cap. So people can decide for themselves whether I’m a B.J.P. person or not.

I hate extremism, whether it is the B.J.P., Muslim League, or whatever. I hate extreme people in any section of society. That is the simplest explanation that I can give.

Some critics have noted that the movie’s concluding musical number highlights key historic figures like [the controversial anti-colonial freedom fighter] Subhas Chandra Bose and [the Indian-nationalist figurehead] Bhagat Singh but omits others, including Mahatma Gandhi and B. R. Ambedkar, which they interpret as a deliberate avoidance of nonviolent revolutionaries. What would you say to that?

By now, I’m tired of answering this question. There are numerous freedom fighters who laid down their lives to attain liberty for our country. I have heard many stories about these freedom fighters from childhood onward. Whichever stories touched me, made me cry, or made my heart swell with pride—those are the historic figures that I chose for that scene. I could also only highlight eight people in that musical number. I would need room for eighty in order to put all the figures that I respect in the movie. Still, I respect all of the revolutionaries that I chose, and, if I didn’t put Gandhiji’s portrait there, it doesn’t mean I disrespect him. I have huge respect for Gandhiji, no doubt about that.

My question is: If I were to replace Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s portrait with Gandhiji’s, would all these people ever question me, saying that I disrespected Subhas Chandra Bose by not portraying him there?

There has also been some criticism of the “Baahubali” films, and now “RRR,” for replicating what they feel is a Brahmanic view of India, particularly how the Kalakeyas are portrayed in “Baahubali 2: The Conclusion.” There’s been critique, as well, of stereotypes regarding Adivasis, particularly Bheem, who has been described as a “noble savage.” Is that just misattributed anxiety and projection?

Yes. [Laughs.] First of all, the Kalakeyas are a completely fictional people. There’s no such caste or tribe, and there are no real-world rituals like what they do in the movie. People are just projecting the Kalakeyas onto real people and then saying that I presented them in the wrong manner. It just makes me laugh. As for Bheem being a noble savage, I don’t really understand how or where I presented Bheem as savage. Noble, definitely, yes. Like when he fights a tiger, and then addresses the tiger as a brother, and even apologizes to the tiger for using him for his needs. I think Bheem is one of the noblest characters that I have written, but I don’t know where the savage part comes in. I really can’t understand that.

Does it feel like the recent rise of nationalism, as well as anti-Muslim sentiment, has affected the way that movies are made in India?

I don’t know. I don’t think in those terms. I always feel like films reflect the society that created them, whatever that society’s feelings are. Films reflect the pace of society because filmmakers have to cater to audiences. They’ll see what audiences like, what their present mood is, and make films for that. If there is a rise in that kind of sentiment in society, those kinds of films will come out. But I always stay away from that. I go a completely different route.

Right, but isn’t there a danger to freedom of expression when political groups try to affect the creative process you’re talking about?

Yeah, those things will happen and they will keep happening. But, if you are clear about what you are making, and if you are clear about who your audiences are, staying true to that will help you overcome those hurdles in communication. That might not be a proper solution to the problem that you are talking about, though. There is no clear-cut solution, but, if you are true to your filmmaking, you will have a better chance of overcoming these hurdles.

When you say, “if you are clear about who your audiences are,” do you mean a mass or a general audience, rather than one determined by a political agenda?

When I say the audience, I imagine people who are coming to theatres and paying some money to get entertained. Entertainment is what I provide. In the audience, there might also be people who have some extreme notions. But just because they are part of my audience doesn’t mean I’m going to cater to those extreme notions.

I distance myself from either Hindu or pseudo-liberal propaganda. I know there are audience members from those extreme groups in my audience. I know that, but I’m not catering to them. I’m just catering to the emotional needs of the audience.

Is there pressure being put on you, whether anti-Muslim or pro-nationalist, from B.J.P. supporters or even the R.S.S.?

No, never directly, never. No one’s ever approached me to make an agenda film, whatever the agenda is. Still, for a long time, less prominent people sometimes found objections to my films. Sometimes Muslims have had objections, sometimes Hindus, sometimes different castes.

Your father has a story credit on “RRR.” Did he help to shape the movie’s characterizations of Bheem and the Adivasis?

The way we write, me and my father, is we write together. It is very difficult to differentiate who is the story writer and who is the screenplay writer. We split the credit as “Story by V. Vijayendra Prasad” and “Screenplay by S. S. Rajamouli,” but we essentially work together on both. It was my idea to write a fictional story about Komaram Bheem and Alluri Sitarama Raju. Once we settled on that, my father developed ideas on how to tell a story based on those characters.

Your father is working on a scripted drama about the R.S.S. He’s said that his opinion of the R.S.S. changed [favorably] once he started working on this project, after which he “understood for the first time what R.S.S. is.” Have you discussed this project with him?

I, myself, am not too aware of the R.S.S. I have obviously heard of the organization, but I don’t know how it was formed, what their exact beliefs are, how they’ve developed, all that. But I read my father’s script. It is extremely emotional. I cried many times while reading that script, many times. The script’s drama made me cry, but that reaction has got nothing to do with the history part of the story.

Is it hard for you to focus on a script like that as just a drama, and not think of its political implications or associations?

The script that I read is very emotional and extremely good, but I don’t know what it implies about society.

I’m assuming you’re asking me, Would I direct the script that is written by my father? First of all, I don’t know whether that would be possible, because I’m not sure if my father has written this script for some other organization, people, or producer. Still, as for the question, I don’t have a definite answer. I would be honored to direct that story, because it’s such a beautiful, human, emotional drama. But I’m not sure about the script’s implications. I’m not saying that it would cause either a negative or a positive impact. For the first time, I’m not sure.

It’s unusual for a Telugu filmmaker, let alone an Indian filmmaker, to have their name foregrounded. Your name is presented as a seal of quality in front of your movies. Where did that come from? Were you trying to distinguish yourself as a filmmaker in light of the star-driven nature of Telugu and Indian cinema?

[Laughs.] At first, it came from a sense of insecurity, a fear that someone would not give me credit for my films. So when I made my first film, “Student No. 1,” no one knew that I directed it. Credit went to the film’s producer, and rightfully so, because he made lots of decisions. He chose the story, the songs, and everything else. So he rightfully got the credit for my first film and I didn’t.

After that, I came up with the idea of putting a stamp on the posters—and on the film—to say, “Hey, guys, don’t ever think this film is made by someone else.” And at the end of my second film, “Simhadri,” I put a credit that says “A film by S. S. Rajamouli.” The film’s producer didn’t like that. He objected: “What does he mean by ‘A film by S. S. Rajamouli’? It should be a film by the whole unit. How can he take the entire credit for the film?”

After a couple of films became successful, I felt odd about the seal. I didn’t want to do it, but by that point the distributors felt it was good to have it. I think it was either for “Yamadonga” or “Magadheera” that the producer said, “From now on, if you don’t put your stamp, the distributor or the audiences will think that you are not confident in the movie.”

In your experiences making films in India, is it normal or unusual to talk about the director as a film’s primary author?

At least until about fifteen, twenty years before the explosion of social media, the general audience didn’t know much about the director. Maybe a few hard-core film fans knew about the director’s role, but movies were predominantly star-driven. Then, when social media became more prominent, directors started figuring out different ways to publicize their films, because we couldn’t show much of the films themselves. We started showing bits of the film and people slowly started understanding, O.K., there is something called direction, and there is someone called a director. He’s the guy who runs the ship.

You’ve made a number of star vehicles with leading men in Telugu cinema. You’ve also varied the types of films you make to showcase your versatility as a director. Are there limits or restrictions that you’ve run into with the star-vehicle model?

From “Simhadri” to “RRR,” no star has ever had doubts about the story as I’ve described it to them. Whenever I describe the story to a producer or a star, I think that they get more enamored by the passion with which I’m telling the story than the story itself. My greatest challenge is usually working within the preliminary budget, which I never have. Trying to not exceed the budget too much [laughs]—that’s the challenge, not dealing with stars.

You’ve been working with the co-leads of “RRR,” Ram Charan and N. T. Rama Rao, Jr., for years now. Do you give direction to them in the same way?

N.T.R. hasn’t changed a bit since we both worked on my first film, “Student No. 1.” He’s obviously improved a lot over the years, though. He always understands what the director is trying to achieve and gives it in an instant. That’s the hallmark of a great actor. We have such a solid understanding between us that I don’t need to tell him anything. He remembers scenes from the first time I’ve described them to him. We have a great rapport. “RRR” is my fourth collaboration with him.

It’s been a different experience with Ram Charan. The first time I worked with him was his second major role, “Magadheera.” He was a bit raw at the time. He had a lot of energy, a lot of charm, and could do his action moves—or dance moves, or sentimental moves—with ease. But he was still learning a few acting nuances at that time. By the time he came to “RRR,” he’d developed a completely new trait, which I haven’t seen with anyone else. Even though he always knows the story—and what he needs to do in a scene—he somehow keeps his mind completely clear. He comes to me and says, “Look, I’m a blank page. You can draw whatever you want on me.” I don’t know how Charan developed that art. I’m a little surprised at any given take; I can never guess what he’s going to deliver. Many times, he bowls me over with the nuances in his acting. He and N.T.R. are completely different actors, and working with both of them has brought me very different kinds of joy as a director.

What would you say that your earlier movies taught you about filming musical performances?

I think the musical numbers in some of my earlier films were not good. [Laughs.] Some were quite experimental, from the beginning. In “Sye,” I love the song where the two romantic leads have a duet, where they harmoniously sing the words on whatever signs and billboards that they pass by. That’s one of my best conceived and choreographed song sequences. Unfortunately, in many of my musical numbers, I’m just trying to show off the actors’ dancing skills, a habit I’m not proud of. By the time I made “RRR,” I no longer put in dance numbers for their own sake. I try very hard to make the audience feel like the musical numbers are not interruption but rather a part of the story.

Are there musical performers, choreographers, or even filmmakers whose work you study or admire? Particularly Indian, but anybody really.

I’ve been an admirer of Prabhu Deva for a long time. He’s a fantastic choreographer. Also, Raj Kapoor, the actor and filmmaker. The way he presents songs is absolutely amazing. And the choreographer that I worked with on “RRR,” Prem Rakshith, I think he is one of the best Indian choreographers ever. He choreographed the “Naatu Naatu” number and I really admire his work.

What was his work on that number like?

I’ve worked with Prem for a long time. and he’s even choreographed some of the action scenes for my films, like “RRR.” Many people don’t know that it was his idea for Bheem to give Raju a piggyback ride on his shoulders.

Prem is a wonderful technician. He understands the needs of the director and the psychology of the audience. In this particular instance, Prem knew that both Ram Charan and N.T.R. have a certain style. Working with them individually is easy, but, when he’s working with them together, their dance steps have to suit both of them. I think Prem took six or seven weeks to come up with the three or four signature moves for “Naatu Naatu.” During that time, he imagined a hundred variations. The Golden Globe Award for “Naatu Naatu” was given to the composer, M. M. Keeravaani, and the lyricist, Chandrabose, which of course they deserve. They did a great job. But I’ve always said, in my capacity as a director, that the main credit for the song’s success belongs to Prem Rakshith.

What makes a great action scene? For example, how did you conceptualize the “RRR” scene where Bheem unleashes a group of caged, wild animals on Raju and a number of British soldiers?

There should be a need in the story, an emotional need, to develop a great action set piece. What happens in the preceding scene is very important: Raju’s just realized that Bheem, his close friend, is the wanted man that he’s been chasing after. Now all the emotional lines of the movie are converging in one spot. The audience knows that Bheem and Raju are going to face off, because we’ve been waiting for that confrontation for the past forty, fifty minutes. All of this sets the stage for an explosive action sequence.

The audience doesn’t care about what I just told you; what they care about is a great visual and emotional connection to what’s happening onscreen. An emotional connection can only happen subconsciously.

I also think, because the foundation for this scene is strong enough for me to build an action sequence, I won’t let anything stop me from thinking of something big, crazy, and really explosive. For this scene, I thought, Bheem is a Gond tribesman, so he needs help to get into this big enemy fort. How would he do that? Where can he get help from? The only person he knows is Raju, and Bheem would not ask him because that would make trouble for Raju. So I thought, Where can he get help? That led me to animals. Once the idea of using animals came into my mind, nothing stopped me from doing all the stuff that you see in the scene.

The masala style, or full-plate style, of filmmaking, where there’s something for every taste, is a hallmark of Indian cinema. The tone of your movies has become more consistent over the years, in the sense that there don’t seem to be as many comic-relief characters. Is that a conscious decision?

It’s not just my films. I think, in many Telugu movies or recent Indian movies, you don’t find the same kind of comic characters inserted into the story line, just for the sake of a few gags. Now most filmmakers try to make these characters a part of the story so that they don’t seem to come out of nowhere. I don’t think I’d go back to bringing in comedians for the sake of laughs. I do, however, understand the strength of a comic scene in, say, “RRR,” when conversation between Bheem and Jenny evokes quite a bit of laughter.

Bheem and Jenny can’t communicate because they don’t speak the same language, so there’s a sort of comedy of errors.

When we wrote those scenes, we felt really happy, but when I was shooting them there was a kind of apprehension. I thought—looking at the other scenes, which are big, heavy, hard-core action sequences, and now suddenly there is a portion of the film with very light, subtle humor—Will the audience feel bored during this part of the film? We still trusted our initial instincts, and when I saw the audience’s reactions in theatres we thought, Yeah, we were right.

By contrast, it’s interesting to see some American critics single out the performances of Alison Doody, Ray Stevenson, and your other British antagonists for being too broad. What’s been your experience with American audiences and how they respond to the British characters in “RRR”?

When I saw their reactions in theatres, they seemed to enjoy the performances. I also read some of the criticisms that you’ve described, about the broad strokes of their performances, and how they’re not similar to the finer nuances of the Indian actors. That surprised me. It wasn’t my intention to make the British characters caricaturish in any way. If the audience feels that way, then that’s my failure.

American viewers who only know you from “Baahubali” and “RRR” have been especially impressed with your abilities as an action filmmaker. What do you think of the quality of action filmmaking in Marvel and other recent superhero movies?

They make extraordinary action set pieces. I mean, the action sequences are the reason I watch Marvel movies. I get engrossed in their action set pieces—I just love them. Their quality, their ingenuity, and their visual compositions—everything is mind-bogglingly good. But one complaint I have: the editing in these sequences is too fast. That kind of pace doesn’t allow me to fully immerse myself in each shot and enjoy them completely. Sometimes you lose a semblance of who is fighting whom, who is hitting whom, and what happened. The action scenes are otherwise great, except for that one small complaint.

Have you seen the new “Avatar” movie yet? And do you like James Cameron’s films?

He’s one of my favorites. I think I love . . . every film of his. [Laughs.] Except for one or two that I missed. “Terminator 2” is one of my favorites, “Titanic,” “Avatar,” “True Lies.” What are his other films?

“The Abyss”?

I haven’t seen “The Abyss.”

You will love “The Abyss.”

I think I’ve seen all of his films except “The Abyss,” and I love all of them. Also, yes, I’ve seen the new “Avatar.” When I watch the “Avatar” movies, I enter a different world. I don’t try to break down what’s happening as far as the story, the character, the emotion, nothing. I get drawn into the world and just watch it. I’ve only seen the new “Avatar” once, so I need to watch it a second and third time.

Have you had time to watch other new movies this past year? And do you have any favorites, especially new Indian films?

I haven’t seen many good recent Indian films. I saw [the Malayalam-language legal thriller] “Jana Gana Mana.” I really loved that.

Can you recommend five essential Indian films that New Yorker readers should check out?

And don’t forget to check out “Eega,” which was directed by somebody called S. S. Rajamouli.

How can contemporary Indian cinema continue to cross over to bigger global audiences? Is that a desirable goal?

That is not an undesirable goal. Some help actually came from the pandemic, when all the entertainment was only provided by O.T.T. [over-the-top services, a.k.a. streaming]. I think that opened things up. People started looking at content from other languages, other cultures. They started understanding and liking stories from outside of their culture. Now I think the world is more receptive. That’s a big advantage, not just for Indian filmmakers but for filmmakers across the world. And, because that receptivity is now there, we have to believe that we have a story that will be liked by everyone. Receptivity alone is not going to help us cross over.

India did not submit “RRR” for the Oscars’ Best International Feature Film category. Do you have any thoughts on why?

It’s difficult to say. As far as I know, the committee has two guidelines: one, the film should represent Indian-ness; and two, it should have a chance of getting nominated or winning the award. That’s what I have heard. We will never know what went into their thought process or their discussions. Dwelling too much on that would also not be right. Those conversations happened a while back already and we are now looking forward, not backward.

“RRR” has given me and my team lots of unexpected accolades, financial gain, and recognition from around the world. We are so content about that. But, for me, an Oscar, or any other critical acclaim, was never on my radar. We didn’t originally think of an Oscar campaign. That started with fans from the West. They were so passionate that we felt, if we didn’t take this forward, we would be doing an injustice to the love that these fans showered on “RRR.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com