Peter Kafka covers media and technology, and their intersection, at Vox. Many of his stories can be found in his Kafka on Media newsletter, and he also hosts the Recode Media podcast.

This story is part of a group of stories called

Uncovering and explaining how our digital world is changing — and changing us.

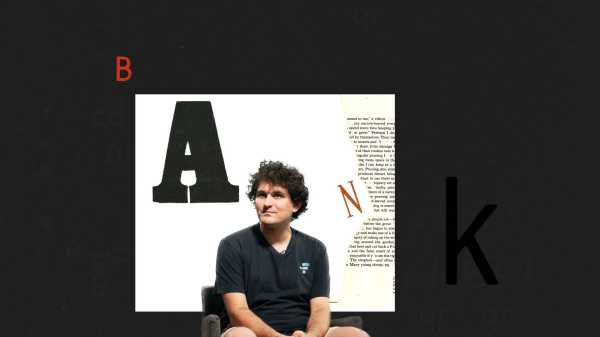

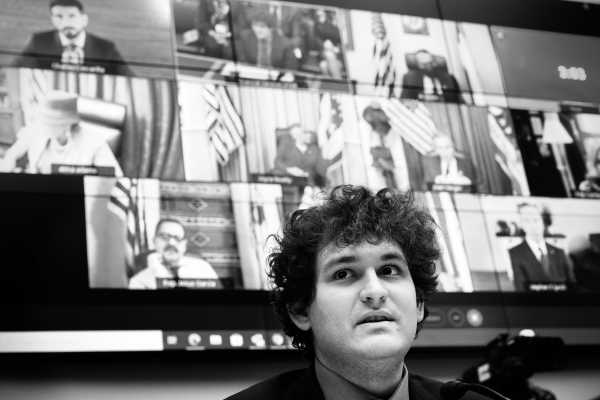

If you are a certain kind of person, you have found yourself entranced by the SBF/FTX story. Billions of dollars have vanished from an offshore crypto operation. Drugs and sex may be involved. (Or maybe not.) In the center is a guy who looks like someone you’d cheat off in pre-calc.

A few months ago, FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried was a power broker handing out piles of cash to … everyone, as well as hosting leaders of the free world on stage; they wore suits, he wore shorts. Now he claims he’s a well-meaning schlub who lost control of the contraption he built and that he’s very sorry.

Me, a guy who covers tech and media? I am definitely in the can’t-get-enough group.

Other people are not entranced at all. They’re angry, or at the very least, confused: Why is the world treating SBF as a story instead of an enormous fraud?

Sign up for the newsletter Kafka on Media

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Email (required)

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Notice. You can opt out at any time. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply. Subscribe

“FTX’s Collapse Was a Crime, Not an Accident,” snarls a headline from CoinDesk, the crypto publication whose reporting poked the first hole in the SBF/FTX story a month ago. “What it definitely was was fraud, and from where I’m sitting it very much looks intentional — and Bankman-Fried looks like a serial liar,” wrote Ben Thompson, one of the tech world’s most influential analysts. “Even the most gullible person should not believe Sam’s claim that this was an accounting error,” tweeted Brian Armstrong, the CEO of FTX rival Coinbase.

From this perspective, SBF is doing a masterful job of convincing people who should know better that maybe he made an oopsie, and not that he made off with his customers’ money. The intrigue and interviews, from their point of view, are letting SBF off the hook. (

The gap between the SBF curious and the SBF haters won’t have anything to do with what actually happens to SBF. That will (likely) be settled by the court system. But it’s worth exploring: Why are some people mostly interested in the SBF story, and others are incensed by it? And does that gap tell us anything about the way people in and around tech view the world? Let’s start by separating the angry-at-SBF crowd by ideology and motivation.

The politicians blaming politicians

This group is pretty straightforward: There’s a scandal — or at least they think people think there is a scandal — and they’re eager to turn it into political advantage. In this case, it’s primarily Republicans who want to lay the blame for FTX on federal regulators, since Democrats control the federal government. And as the Atlantic’s James Surowiecki notes, much of this is blatantly hypocritical, even by political point-scoring standards: The same politicians — like Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) — who say the US government didn’t do enough to protect crypto traders in this case had previously complained that the US government was harassing crypto companies like FTX.

There’s a second, related version of this critique, which lumps together Democrats with the press — Republicans’ other favorite punching bag — and suggests that SBF’s donations to politicians and journalists convinced us to ignore or cover up the FTX story. Under this theory, that money is still convincing us to soft-pedal his alleged crimes.

It’s reasonable to question why journalists didn’t pierce the FTX story earlier; I put that query in the same category of self-reflection that some of us undertook after the 2008 financial crisis. But it’s dumb to argue that SBF bought himself good press coverage: For starters, the most persuasive thing you can use to sway journalists isn’t cash, but a good story. And for a couple years, whiz-kid billionaire SBF was a very good story.

But now he’s an even better story, which is why there’s a steady flow of reporting about the goings on at his collapsed crypto company. Which is the same reporting SBF haters are using to complain about the press.

The don’t-blame-crypto crowd

This one is also relatively easy to unpack: If you are in crypto, you are very angry at SBF because you think he’s making your bad time worse.

After captivating the world for a couple of years, crypto has been in meltdown for much of 2022, which means investors in crypto coins and projects have lost money, people who thought they were working on The Next Big Thing are having second thoughts, and Miami no longer seems so appealing. Now comes SBF, and he’s adding insult to injury: If the crypto doubters already thought crypto was a scam, now they have even more evidence.

Which is why so many crypto people are taking great pains to argue that SBF and FTX weren’t really crypto people: Yes, they made money by betting on crypto and letting their customers do the same thing, but they weren’t theologically connected to crypto. It was just a thing they bought and sold, like orange juice futures.

A common argument you’ll hear from crypto folks is that FTX by its very nature — a centralized platform to buy, sell, and borrow crypto — isn’t a “real” crypto operation because real crypto is supposed to be decentralized, with no SBF in the middle who can meddle with the whole thing. (“Not your keys, not your coins” is a thing crypto people say.)

But even people who aren’t ideologically married to a specific version of crypto still see SBF as a big step backward for the industry, which was already riddled with stories about bad behavior.

“It’s frustrating to see what a lot of people in crypto see as a built-in bias against the industry, which many of us understand because this space does have a side to it that deserves and requires scrutiny,” says Rachael Horwitz, the chief marketing officer for crypto investor Haun Ventures. “But there are people genuinely interested in building, and they’re not given the benefit of the doubt; it’s given to a guy who said all the right things to knock the industry.”

The what-can’t-you-see people

This is the group that’s most fascinating to me because they don’t have an obvious dog in this fight. But they still think there’s one clear side in this, and that’s the one that treats SBF as a criminal who made off with billions of his customers’ funds.

“I personally am not angry. I’m more befuddled,” Ben Thompson told me when we talked this week. “I think [the press and everyone else] should be taking [SBF] at his word. Which means that fraud was committed.”

While Thompson acknowledges that crypto is complicated and that the FTX case marries crypto with relatively arcane trading and accounting knowledge, he says the basic idea behind the story should be easy for anyone to understand: SBF took money customers deposited in FTX, his trading platform, and moved it over to Alameda, the hedge fund he owned — a big no-no specifically ruled out in the company’s terms of service. This is an argument you hear a lot from exasperated tech people: “What’s so difficult to understand about this?”

A related version of this: frustration with the fact that SBF is talking and talking and talking from a compound in the Bahamas, where FTX was located, instead of a jail cell. Bernie Madoff, many people have noted, was arrested the day after he told his sons he’d been running a massive Ponzi scheme, and pleaded guilty to federal charges a few months later.

But as former federal prosecutor Ankush Khardori explains, “Those who are eager to see Bankman-Fried charged with serious financial crimes will just have to be patient.” It’s not uncommon for prosecutors to bring charges more than a year after a complex financial crime has surfaced, and this could be a very complex one, which also took place outside the US. And, unlike Madoff, SBF continues to insist he didn’t commit fraud.

Then there are people who are less upset about the particulars of SBF and more about the model they say he fits: The genius tech founder who dazzles the world, screws up, and then finds plenty of people willing to give him the benefit of the doubt, or even more.

In other words: a dude.

“He is not being held to the same standards as women leaders who have more minor missteps,” says Sara Mauskopf, the founder and CEO of Winnie, a child care startup. “Women, if they are slightly aggressive to their employees, they are erased from the face of the earth. But for male leaders, you can swindle people out of a billion dollars … It’s amazing to me that we’re still debating whether he’s really a bad person or whether this is fraud.”

I’ve heard that critique often over the last several years, usually following a story about a blow-up at a female-founded company like Away or The Wing. This time around, I tried positing the theory that people weren’t furious at SBF because they might genuinely be confused about an offshore crypto shop that was built for “prosumers” interested in things like margin accounts. Mauskopf wasn’t having it.

“A year ago, everybody was a Web3 expert. Now suddenly it’s too complex for people to weigh in on?”

Why aren’t you mad, bro?

I do think that simple confusion — or, at least, the lack of an obvious smoking gun like an “I’m guilty” admission — may be enough for some people to chalk this up as fascinating but not enraging. My former boss, Henry Blodget, the Wall Street analyst turned publisher — who himself was charged with securities fraud in the aftermath of the dot-com bubble (Blodget settled the case without admitting to or denying the charges) — suggested as much last week, with a tweet that then enraged the lock-’em-up crowd:

But I think the key element that explains the lack of widespread fury around SBF is one that won’t satisfy many of his critics: Even though SBF’s face showed up on plenty of magazine covers, and the FTX logo appeared on sports properties and TV screens, the average person likely didn’t know much about him or his company. And unlike Blodget after the dot-com crash or Madoff in the great recession of 2008, SBF doesn’t make a good stand-in for the “guy who took your money” role.

That’s in part because SBF likely didn’t take your money. While FTX had a million creditors, most of whom were customers, that’s a tiny fraction of people who played with crypto over the past few years. And I’d argue that if you did lose money in crypto, it’s much more likely that you did it the old-fashioned way: hopping on Robinhood and buying bitcoin at $60k — it’s now at $17,000 — or dogecoin at 64 cents, minutes before Elon Musk went on Saturday Night Live and called it a “hustle.” It’s now at 3 cents, as my app reminds me.

And it may just be that despite all the inroads crypto made into the mainstream over the last decade — SNL doesn’t do jokes about cryptocurrencies unless a lot of people have heard about those cryptocurrencies — it still isn’t fully mainstream. Which is why the crypto crash that has sucked $2 trillion out of the market doesn’t feel like something that has leveled lots of people in the way the 2000 and 2008 crashes did.

Again, none of that will have much to do with the way the legal system treats SBF, though there is certainly a theory that his “I’m just a nerd who made a nerdy mistake” semi-explanations are aimed at softening up potential prosecutors, judges, and juries. We’re unlikely to see how that pans out for a long time.

Sourse: vox.com