If written today, “In Search of Lost Time” might well be an Internet novel. The Web has become the first port of call in any search for what we’ve once seen or even felt. It’s our externalized memory—in the never-fading photographs on Instagram or Facebook, in the dangerously searchable chats, the indelible e-mails, or in our improbably granular Uber and Venmo histories. Our memory also lives, in part, on YouTube: every movie scene you’ve ever watched; every historical event you’ve ever (or never) witnessed; tours of every place you’ve ever visited; and recordings of every song you’ve ever listened to, or cried to, or loved to. But the thing about a shared memory is that it’s not just yours—though you may recall it on your own, so can anyone else. And they leave comments.

Chiara Amisola, an artist from the Philippines, believes that the YouTube comments section is “one of the last sacred spaces of the internet.” In contrast to the hypercuration of the social-media profile, anything goes in the comments. Amisola is fascinated by the commenters who, as she puts it, “gush out stories (real or fake?) about falling in love, being saved, or just tripping madly to some low qual upload of a post-rock song,” she wrote in an Instagram post. Clicking on a song uploaded more than a decade ago, you end up falling down a rabbit hole—or hundreds of rabbit holes—if you take a look at the archive of feeling that unfurls beneath the video, like some mixture of bathroom-wall graffiti and Talmudic commentary.

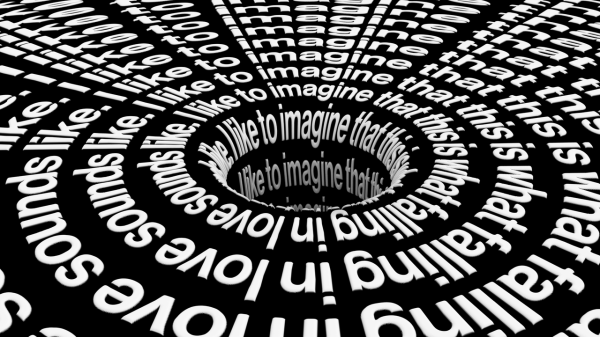

Thesoundof.love, a “web experience” Amisola created this past Valentine’s Day, explores “the rawness of human intimacy and confession in the YouTube comments left under love songs.” The page is minimal: each comment appears in large black text above the video in question, which plays inside a small circle that rotates like an LP. YouTube’s hierarchy is reversed: the comment is moved from the margins to the center, taking the place normally occupied by the video, and the milky white background, free from ads and alerts, becomes a blank canvas for imagination. Most of the videos are still images or album covers; when there is, say, a performance of the Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows,” you can watch it without too much trouble, but the videos are more to be glimpsed than watched. We’re instead asked to pay attention to the text.

If it sounds like a reach, it often is. Many of the comments match the dime-store sentimentality of the songs—often indie and prog rock—that they comment on, redolent of online mawkishness and marked by the Internet’s pervasive fetishization of trauma. There are many wishes to be stronger or better, memories of long walks and talks in woods and fields, fervent messaging, long phone calls that go deep into the night, regrets, mistakes—in general, lots of high school. But there are also some statements that have a near-poetic texture and lift. “Now I’m on the other side guys, love is beautiful,” reads one comment, on “Poison Oak,” by Bright Eyes. Another, on “Friendships and Love,” by Rocketship: “sitting in Union Station at the end of summer and realizing that everything is going to change very soon.” The language isn’t eloquent but the image is, and the fragmentary form, like a single remembered line of verse, leaves a suggestive echo.

Most of the comments are sad, laden with pathos that is often amplified by the Internet-inflected language in which they are written. There is something inscrutably poignant about a memory of a recently deceased grandmother or the wistful recollection of touching a lover’s hair that’s punctuated with “lol” or “lmao.” The canned, unschooled, even naïve language is, in this context, a marker of authenticity, a touch of nature. The underlying point is simple but important: everyone, no matter how well they can express it, sometimes wants to relive the warm glow of youthful love, or to remember how they danced on their wedding night, or, with that repetition compulsion that we all have, to listen to a song that was the soundtrack to a breakup. Many would share these emotions and memories only with their closest friends, or their diary. For some, though, the comments section—like their Twitter feed, or their Instagram page—might well be their diary.

These comments are evidence of a song’s work in the world, testimony to the multitude of ways it can be meaningful. Every song, like every work of art, cultivates an invisible community of those in whom it resides, and proves the point, over and over, that there is no such thing as a unique feeling, a unique love. Or, rather, that shared feelings and experiences are always shared differently, and they can exist in tension. “The same guy who has loved me since I was 16 years old dedicated this song to me,” someone writes about “Pictures of You,” by the Cure. “I’m 43 now and no one will ever love me or understand me the way he does.” The same song makes another person think of her boyfriend Chris, who took his own life. “When he was laid to rest they buried him with a suit that he wore when we went to our last prom, the guitar necklace I gave him for Christmas that December and finally the polaroid picture he took of me at the lockers and they had put it in his pocket close to his heart,” they write. “This song goes out to you Chris and to all who suffer loss but are brought together out of love.”

The juxtapositions sometimes have the disorienting extremity that marks the scroll or the feed, where the utterly banal is jumbled together with the devastating—of which we’re simultaneously reverent and, in the Internet’s anonymous and unverified economy of affect, suspicious. “I Will Follow You Into the Dark,” by Death Cab for Cutie, reminds one person of a suicide pact that they had with their friend, from which (the commenter claims) they were saved only by their mother’s intervention. On the same track, a commenter writes, “i sing this song to my cat who is getting pretty old. i’ve lived my entire life with her, and i honestly love her more than anyone in the world. living without her won’t really be living.” One of the strangest and most wonderful comments, on “Talking,” by Haruomi Hosono, recounts an impromptu funeral, in the Netherlands, for a green parrot that the commenter found lying on its back on the ground. “We carefully put it in a cardboard box filled with leaves, and later buried it underneath a tree in the park nearby, next to a raspberriebush that my foraging friend found,” they write. “During this entire funeral we had my mobile phone playing this first song in the background . . . from this exact YouTube-video.” In the talky second-person register that marks so many of these statements—most of which are consciously addressed to an audience of fellow-listeners—the commenter signs off: “I hope you all have a beautiful day, and a beautiful night.”

The Internet’s archives of human emotion prove the grand community of experience on a scale that, even a couple of generations ago, was unthinkable: even in the far reaches of YouTube comments, the most throwaway of online forms, we can find a record of the millions of private memories and feelings that flood our world like invisible radio waves. In their often hackneyed and humble language, the comments collected on thesoundof.love, an infinitesimal fraction of this motley corpus, point toward just how much feeling there is and will always be out there—how much longing, how much regret, how much love that, like the Internet itself, haunts our collective reality even when it can’t be seen. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com