Alabama Solicitor General Edmund LaCour came to the Supreme Court on Tuesday with a raft of ambitious arguments — many of which would dismantle one of the key remaining prongs of the Voting Rights Act, and potentially give states broad authority to draw legislative maps that favor white voters at the expense of racial minorities.

Not long after LaCour began to lay out his case in Merrill v. Milligan, however, it appeared that many of his arguments are so fundamentally flawed that even this Supreme Court is unlikely to sign on to them.

Republican appointees Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Amy Coney Barrett both pointed out that his proposed reading of the Voting Rights Act cannot be squared with the law’s text. Even Justice Samuel Alito, the Court’s most reliable partisan, acknowledged that LaCour offered some proposals that are “quite far reaching” and others that are more “basic,” and he seemed to urge LaCour to stick to his more “basic” ideas.

Help inform the future of Vox

We want to get to know you better — and learn what your needs are. Take Vox’s survey here.

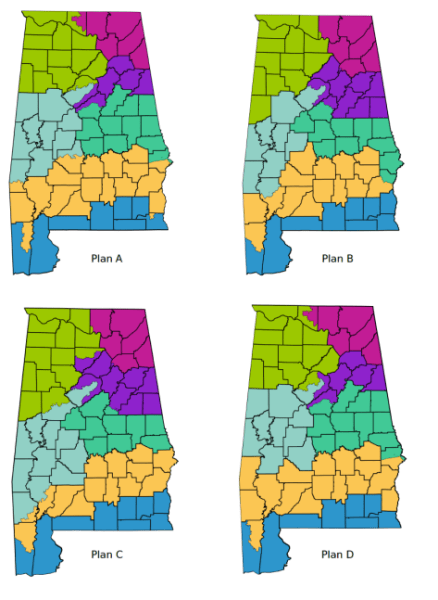

None of this means that Alabama is likely to lose this case. It’s fighting to keep congressional maps that allow Black Alabamans to elect their preferred candidate in only one of the state’s seven districts — or 14 percent of those districts — although Black people make up about 27 percent of the state’s population. Two different sets of plaintiffs argue those maps violate the Voting Rights Act’s prohibition on race discrimination in voting.

But several of the justices, including Roberts, Barrett, and Justice Brett Kavanaugh, seemed to spend the morning casting about for a way to rule in Alabama’s favor without explicitly overruling nearly four decades of established voting rights law stretching back to the Court’s decision in Thornburg v. Gingles (1986).

That won’t be an easy task. Justice Elena Kagan said early in Tuesday’s argument that the Merrill plaintiffs’ challenge to Alabama’s maps is a “slam dunk” under Gingles and the Court’s precedents following Gingles. A lower court’s three-judge panel that included two judges appointed by former President Donald Trump agreed with Kagan, saying that the question of whether Alabama violated the law is not “a close one.”

But a majority of the justices seemed disinclined to announce a broad, sweeping reinterpretation of the Voting Rights Act that ignores much of the law’s text. And they also seemed disinclined to overrule Gingles and replace it with one of Alabama’s proposals to legalize many forms of racial gerrymandering that have historically been forbidden.

Based on oral arguments Tuesday, the most likely outcome in Merrill is a narrow decision for Alabama, bailing out the maps drawn by the state’s Republican-led legislature, but holding off for another day the question of whether to legalize many forms of racial gerrymandering en masse.

To be clear, such an outcome is not a victory for proponents of voting rights. This Supreme Court, with its 6-3 Republican-appointed majority, appears eager to centralize power within itself, and to maximize its own authority to decide cases according to a majority of the justices’ policy preferences. A narrow ruling could hand Alabama a victory, without limiting the Court’s discretion in future racial gerrymandering cases.

But, at the very least, Alabama seems unlikely to win a sweeping decision that explicitly eliminates voting rights protections that have existed for nearly 40 years.

Alabama wants to cut off racial gerrymandering suits before they even really begin

Under Gingles, plaintiffs alleging that a legislative map violates the Voting Rights Act must clear a long list of hurdles. First, a plaintiff claiming that a state must draw additional districts where a racial minority group can elect their preferred candidate must show that this group is “sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority” within an additional district.

Normally, voting rights plaintiffs accomplish this task by drawing one or more sample maps that include a sufficient number of majority-minority districts. So, for example, because the plaintiffs in Merrill allege that Alabama should have a second majority-Black congressional district, they needed to produce at least one sample map where Black people comprise a majority in two districts.

As Justice Kagan has explained, the purpose of making voting rights plaintiffs produce a sample map is to show “that what they are asking for is possible.” If it is not actually possible to draw congressional maps with two Black-majority districts in Alabama, then there is no point in litigating whether Alabama should have two Black-majority districts.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that, under Gingles, plaintiffs who produce a valid sample map do not necessarily win their case. Indeed, all they achieve is that they prevent their case from being tossed out at an early stage. Gingles still requires voting rights plaintiffs to prove other facts. They must prove, for example, that a state’s white voters tend to vote “as a bloc to enable it … usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.”

And Gingles also requires judges to consider a myriad of factors, such as whether the state in question has a “history of official discrimination” or “whether political campaigns have been characterized by overt or subtle racial appeals,” before it can declare a map invalid. Again, the sole purpose of the sample map is to make plaintiffs show their proposed outcome is possible before many of the difficult questions raised by racial gerrymandering lawsuits are even litigated.

Nevertheless, Alabama’s LaCour urged the Court to impose new obligations on plaintiffs when they draw their sample maps, some of which could make it impossible for any plaintiff to challenge a racial gerrymander under the Voting Rights Act. One of his primary arguments, for example, is that these plaintiffs may not take too much account of race when they produce these sample maps — even though it is unclear how, exactly, a plaintiff is supposed to draw a sample map that includes two majority-Black districts if they aren’t allowed to consider race while doing so.

Even Alito appeared to think that the strongest version of this argument goes too far. He urged LaCour to focus on a more refined version of his argument — that the sample maps must feature “the type of district that would be drawn by an unbiased mapmaker.”

As many justices pointed out, however, this approach is at odds with the text of the Voting Rights Act, which says any state law that “results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color” is illegal, even if that law is not motivated by racial bias. Indeed, Congress inserted this results-focused language into the statute in 1982 for the very purpose of overruling the Supreme Court’s decision in City of Mobile v. Bolden (1980), which held that Voting Rights Act plaintiffs must prove racist intent in order to prevail.

That said, Alito soon made clear he’s advocating for a rule that requires plaintiffs to produce sample maps that meet what are often described as “traditional redistricting criteria,” such as drawing compact districts or keeping “communities of interest” — groups of people who share a similar culture, economic interest, or livelihood — together in a single district.

But, as Kavanaugh pointed out, it’s far from clear that such a focus on traditional criteria would lead to the result Alito wants. The plaintiffs’ proposed districts, Kavanaugh noted, do not have a “bizarre” shape and appear to be “reasonably compact.”

All of which is a long way of saying that there probably aren’t five votes on the Supreme Court to impose impossible new obligations on plaintiffs alleging racial gerrymandering at the earliest stages of litigation. But that does not mean that Alabama is likely to lose its case.

Several of the Court’s Republican appointees seemed to be looking for a way to decide this case narrowly

The Court’s Republican-appointed majority is normally quite hostile to Voting Rights Act plaintiffs. And it’s worth noting that, after a lower court struck down Alabama’s maps, the Court voted 5-4 to reinstate those maps during the 2022 election. Tuesday’s hearing concerned whether the Court should permanently reinstate the maps.

Most of the justices did not explain why they voted to temporarily reinstate the maps for 2022, and Kavanaugh wrote a brief opinion at the time indicating that he voted in Alabama’s favor in part because he thought the lower court’s decision was ill-timed. Nevertheless, given that the Court has already voted in favor of these maps once, it seems unlikely to reverse course.

But it is far from clear how the Court will get to that result. Of the justices who spoke up on Tuesday, only Alito appeared enthusiastic about a decision that would significantly rework the Gingles framework (although Justice Clarence Thomas only spoke briefly at the beginning of the argument, and Justice Neil Gorsuch was silent).

The other three Republican appointees — Roberts, Kavanaugh, and Barrett — all asked questions that seemed to be looking for a way to rule in Alabama’s favor, but largely by relying on factual circumstances particular to this case.

Much of the argument, for example, focused on the fact that some of the plaintiffs’ expert witnesses ran computer simulations to draw maps, using criteria that accounted for some, but not all, of the traditional race-neutral factors often considered in redistricting. These simulations did not produce any maps with two or more Black-majority districts. (One of the plaintiffs’ briefs argues that these simulations are irrelevant, because the simulated maps did not account for some traditional redistricting criteria such as keeping communities of interest together.)

Again, Gingles does not require voting rights plaintiffs to produce a sample map using computer simulations. It merely requires them to produce a sample map using any method they choose. But Roberts asked three times whether the Court could consider these simulations among the “totality of the circumstances” that might support a ruling in Alabama’s favor. And Barrett zeroed in on the computer simulations as well.

Future voting rights plaintiffs could avoid this problem by simply not running computer simulations. But Roberts and Barrett, at the very least, may look to the simulations as a reason to rule against these particular plaintiffs.

Kavanaugh, meanwhile, asked questions of both sides about whether the plaintiffs’ proposed maps were sufficiently compact. Based solely on his questions Tuesday, it’s possible that Kavanaugh may ultimately vote with the Court’s three liberals to strike down Alabama’s maps — although four votes would not be enough for the Merrill plaintiffs to prevail.

Our goal this month

Now is not the time for paywalls. Now is the time to point out what’s hidden in plain sight (for instance, the hundreds of election deniers on ballots across the country), clearly explain the answers to voters’ questions, and give people the tools they need to be active participants in America’s democracy. Reader gifts help keep our well-sourced, research-driven explanatory journalism free for everyone. By the end of September, we’re aiming to add 5,000 new financial contributors to our community of Vox supporters. Will you help us reach our goal by making a gift today?

Sourse: vox.com