Share

Tweet

Share

Share

The big divide among 2020 Democrats over trade — and why it matters

tweet

share

Part of

Vox’s guide to the 2020 presidential candidates

It’s a pretty safe bet that no candidate is going to campaign as a free trader in the 2020 Democratic primary, setting up the potential for a large-scale realignment on a major policy issue for the party.

The Democratic Party faces a fork in the road, on an issue where President Donald Trump has scrambled all the old alliances.

“I think we’re at a tipping point,” says Thea Lee, who leads the lefty Economic Policy Institute, which is skeptical of free trade agreements. “You could see Democrats retreat to their comfort blanket. My hope is we can convince people that’s not an option. We’re not going to go back to the status quo ante. What we need to do is have a forward-looking vision.”

Former Democratic Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, in part because of their decision to work with congressional Republicans, put the party on the path of free trade. They pursued trade liberalization in service of embracing global competition; the left’s dire warnings of jobs shipping overseas went unheeded. Then Trump staged a protectionist takeover of the Republican Party on his way to the White House.

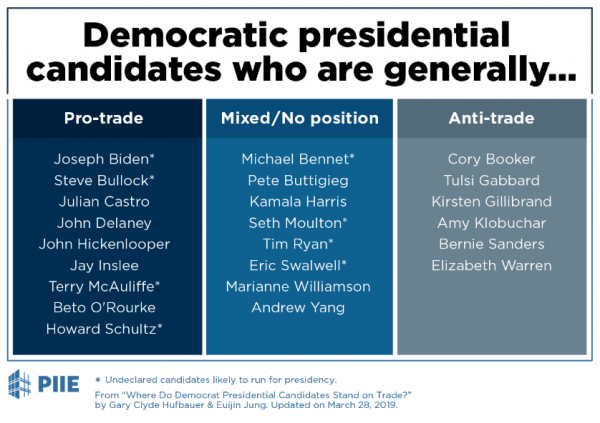

Conversations with aides to 2020 contenders show Democrats are all over the map on trade. There’s a contingent of vocal trade skeptics, like Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders who are making the case that Trump — despite all his tough talk on trade — has not been aggressive enough to protect American workers and failed to live up to his promises. Trade-friendly Democrats like former Rep. Beto O’Rourke and former Vice President Joe Biden could stake out more of a Clinton/Obama-esque free-trade position in this debate. Stuck between are the likes of Kamala Harris and Pete Buttigieg. Harris, particularly, has had to answer to the demands of a global California economy without alienating the left-wing grassroots.

One chart, from the Peterson Institute, breaks down the 2020 Democratic field. The institute’s experts observed “Democratic contenders offer widely different perspectives on US trade policy, and thus on US engagement with the world in a post-Trump era.”

Democrats are on the cusp of a fundamental reorientation for their trade agenda. How 2020 Democrats respond to Trump’s brinksmanship will go a long way to define the United States’ future role in the global economy. Trade is one issue where the president has a lot of freedom to set his or her own agenda once in office, even if a president ultimately needs Congress to ratify new trade deals, giving the Democratic left a real chance to reorient the country’s trade policy if one of their candidates prevails.

Democrats have been trade-skeptical for a long time

Manufacturing jobs have dropped precipitously in the United States over the past 50 years. Thousands of American workers were left unemployed when the massive GM plant in Lordstown, Ohio, closed while the company has been increasing production in Mexico, and when the textile industry in North Carolina moved to cheaper labor markets in Brazil, China, Vietnam, and Bangladesh. The labor unions decimated by that macroeconomic trend make up an important piece of any Democratic primary coalition.

Trade skeptics point to multinational companies moving US jobs overseas as one of the material consequences of US trade agreements, an argument Trump adopted during the general election and in the White House. Progressives believe free trade has done more to line corporate pockets than protect workers or the climate.

“Do trade agreements protect multinational corporations that want to outsource and earn big profits and not be subject to a lot of annoying government regulations, or should they protect workers and consumers and the environment?” Lee says. “I would argue right now we don’t have the rules right. We’ve adopted a very corporate approach to trade.”

Democrats have always been more skeptical of trade, but a reorientation at the top of the party in the 1990s led the two most recent Democratic presidents to aggressively pursue free trade deals. Before that, Republicans were the ones seeking the free trade agreements, with a narrower sliver of mainstream Democrats joining them over the objections of their left wing.

The North American Free Trade Agreement — despite Trump’s claim that it was “given to us by Bill Clinton” — was originally negotiated by Republican President George H.W. Bush. Nearly half of the House Democratic conference, along with a handful of conservative Republicans, voted against it. Labor and environmental groups decried the deal as too weak, and many feared the jobs that would be sent overseas. Even the two top Democrats — House Majority Leader Richard Gephardt and House Majority Whip David Bonior — opposed it at the time. Likewise, the Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA), George W. Bush’s expansion of NAFTA, passed in 2005, almost entirely with Republican support; only 15 Democrats signed on to it.

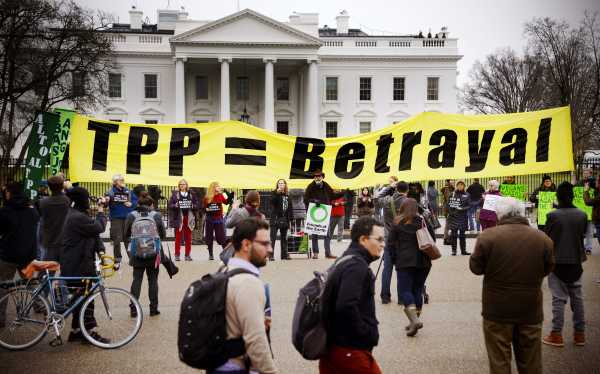

And the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a behemoth trade deal between countries bordering the Pacific Ocean, including the United States, Mexico, Canada, Japan, Vietnam, Australia, and Chile, which was supposed to be Obama’s liberal successor to NAFTA, died after the 2016 election, on the strength of opposition from not only Trump but also from progressives. It became so politically untenable that Hillary Clinton, who praised the deal during her time as Obama’s secretary of state, withdrew her support during the primary election in 2016.

Her move showed that even the Obama-style trade liberalization was going to be a hard sell for Democrats. That is only truer heading into 2020, as Trump’s decision to rip up the old rules about trade has emboldened progressive Democrats who see an opening to outflank the president on one of their core issues.

Some Democrats genuinely thought you could balance trade with populism. It hasn’t work out.

Obama, who had voted against CAFTA in his first year in the US Senate, railed against outsourcing jobs on the campaign trail. He said he would renegotiate NAFTA, calling it “devastating” and “a big mistake.”

But as president, he adopted the more trade-friendly stance that trade was merely a scapegoat for other economic factors — globalization, first and foremost — a belief that permeated his administration as it went to work on the TPP deal that would eventually fail.

“Trade agreements are how you shape globalization to reflect our interests and our values,” Mike Froman, who was Obama’s US trade representative, told Vox. “Since you don’t get a chance to vote on technology or even globalization, trade agreements have become the scapegoat for other quite legitimate concerns about jobs and wages.”

Free trade proponents argue most of the job losses in manufacturing have actually been the byproduct of better technology, not trade. They assert the benefits of liberal trade are real but more diffuse — lower prices for consumers on a wide range of goods, namely — while the drawbacks tend to be acute, like when a factory closes because its production is moved elsewhere.

A decade ago, George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers estimated that each American household had reaped $10,000 in benefits on average that could be attributed to more liberal trade after World War II.

“Increased trade has made the United States more productive and has contributed to large increases in the U.S. standard of living,” the report stated.

Democrats who believe in free trade make the case that more investment in a social safety net and domestic programs would alleviate some of the populist anger over trade. For example, building a robust jobs retraining program would help to combat the effects of outsourcing.

Some programs do exist; Trade Adjustment Assistance, a 1960s entitlement program that has been expanded over the years, offers unemployment benefits and jobs training programs. But the results have been mixed; younger participants typically fare better than older workers, who generally suffer more financially from outsourced jobs. But those who did enroll in the jobs programs did better than those who did not.

Part of the problem is that the two sides disagree on whether they are even having the right debate. “It’s not either-or. It’s both,” Lee says. “The comfortable fiction that trade is blameless and it’s all technology is not supported by the facts.”

How 2020 Democratic candidates are positioning themselves on trade

For Democrats, the 2020 primary will center on the question of credibility. The Obama and Clinton compromises on trade have made hawks more cautious about other contenders with less established records. The left is eyeing much of the 2020 field warily for that reason.

Bernie Sanders has opposed just about every free trade agreement that’s come before Congress since they got there in early 1990s. Elizabeth Warren, who fiercely opposed the TPP, enjoys the same cache with the left. They’ll argue that Trump’s real record hasn’t matched up to his populist rhetoric.

The free trade skeptics believe in those two. “They’ve saying that stuff for a long time,” Lee says. “I have less confidence in some of the people who have been all over the map and now want to appeal to voters after having been in a lot of different places. That’s been a pattern with Democratic politicians in the past.”

Cory Booker and Amy Klobuchar have also generally opposed free-trade deals in office, though it is not a signature issue for them in the same way it is for Sanders and Warren. Still, Booker opposed giving Obama fast-track authority for TPP as did Klobuchar, who also voted against the Central American free trade agreement in 2006.

Biden, if he runs, has a worker-friendly image, but he will inherit the free trade mantle as a veteran of the Obama administration. Beto O’Rourke voted for the TPP deal in the House, which might make him unacceptable to trade hardliners, though he said during his Senate campaign last year that he wanted to see an improved NAFTA negotiated in the coming years.

“We cannot lose that critically important relationship with Mexico and Canada and, by extension, the rest of the world,” O’Rourke said last April. “Whether it is the energy we produce, whether it is the cotton we grow, whether it is the cattle we raise, all of this has a connection to the rest of the world and very often is looking for a market somewhere else.”

Somewhere in the middle sits Kamala Harris.

The TPP was one of the hottest issues in politics during Harris’s 2016 Senate campaign, and Harris initially declined to take a firm stance on it: “We want to strike a balance that allows America’s economy to prosper, and that’s going to be about our workers and our businesses,” she said in April 2015, neither endorsing nor really opposing the trade deal. But once Rep. Loretta Sanchez, a fierce TPP critic, entered the race against her, Harris came out against the trade pact, stating it did not adequately protect US workers or the environment.

Since then, Harris has sat at every intersection of the trade debate. She talks about giving workers a voice and protecting American jobs. But she doesn’t approve of Trump’s protectionism, a trade regime that she sees as destroying the United States’ international relations, as well as taking a toll on consumers and manufacturers.

Democrats will decide their post-Trump trade agenda in the 2020 primary

In real-world policy terms, the debate is really about trade agreements and, to some extent, the World Trade Organization. It’s about which rules are set for trade and which rules are enforced.

Trade agreements are negotiated by the administration and given preferential treatment for speedy approval in Congress — that’s why trade is an issue where presidents can have enormous influence. Those agreements are filled with “chapters” — rules, or the basis for rules and regulations rather, on specific issues like intellectual property and labor rights and environmental protections. The president picks the people who wrote these trade agreements and those rules. Trump has not only introduced his headline-grabbing tariffs, but the White House has also overseen the rewriting of a North American trade agreement.

Left-wing Democrats like Warren, and Sanders do not want to go back to the Obama brand of open trade policy. So they have to now distinguish their protectionism, which Sanders popularized on the national political stage during the 2016 election, from Trump’s.

Some of their solutions can feel a little abstract — “negotiate better trade deals!” Not far afield from what Donald Trump was promising during the 2016 campaign. It’s a weakness even lefty wonks recognize.

“To be honest, it’s something I would like to see all of us on the progressive side spend a lot more time fleshing out,” Lee says. “What does a progressive globalization trade agenda look going forward? People have a little bit of a hard time articulating it.”

Meanwhile, more free trade–friendly Democrats have a completely different challenge; their positions on trade are easily distinguishable from Trump’s (they largely support free trade) but politically dangerous with the progressive grassroots.

Americans broadly are actually more positive toward trade liberalization (and wary of protectionism) than the rhetoric from the current president or the progressive firebrands might lead you to believe. There is an audience for it. But not necessarily in a Democratic primary.

Sourse: vox.com