Weeks before the midterms, a political drama is unfolding in Pennsylvania: A state committee to investigate crime in Philadelphia could ultimately impeach the city’s twice-elected district attorney Larry Krasner, who ran on a platform of reducing mass incarceration and the criminalization of poverty.

Republicans say their investigation is about seeking solutions for rising crime, but for the past five years, they’ve been eager to connect their anti-Krasner rhetoric to the broader Democratic Party — a narrative that has fueled backlash against progressive prosecutors in other cities and painted Democrats as anti-police. Pennsylvania’s investigation started just weeks after San Francisco voters recalled their progressive prosecutor Chesa Boudin.

Krasner’s allies see the probe as a cynical stunt by a Republican-controlled legislature that both underfunds Philadelphia and blocks its leaders from passing tougher gun laws. They also view it as a dangerously anti-democratic effort to overturn the will of Philadelphia voters — akin to the effort to overturn the city’s votes for Biden in the 2020 election.

The committee, dubbed the Select Committee on Restoring Law and Order, was voted into existence by nearly all House Republican lawmakers in June. It’s already embroiled in one legal battle with Krasner, who has objected in court to their sweeping request for documents. To impeach Krasner, the committee might have to demonstrate evidence of misbehavior or corruption — not just ideological disagreement — and that could end up being the subject of yet another court fight.

The backdrop to all of this is the midterm elections. In Pennsylvania, there’s a tightly contested US Senate race where the Republican candidate, Mehmet Oz, has made crime the focus of multiple attack ads. The governor’s race also has implications for 2024 and beyond: The current Republican nominee, Doug Mastriano, led the effort to overturn Pennsylvania’s votes for Biden two years ago.

Mastriano, who is now trying to defend himself against accusations of being anti-democratic, has become one of the few high-profile GOP officials to defend Krasner against impeachment, calling the inquiry “political grandstanding.” And dozens of Democrats, including Democratic lieutenant governor candidate Austin Davis, voted with Republicans in September to hold Krasner in contempt for refusing to comply with a subpoena. (Krasner argued in state court that the committee’s subpoena was illegitimate and illegal.)

Some other Pennsylvania Democrats are seeking to distance themselves from the controversy. Democratic Senate candidate John Fetterman, who has been running ads about “funding the police,” has not weighed in, and gubernatorial candidate Josh Shapiro’s campaign also declined to comment.

The committee pledged to produce a report with its findings and recommendations by “the fall” — coinciding with the 2022 midterms.

A pioneering progressive prosecutor confronts rising crime in Philadelphia

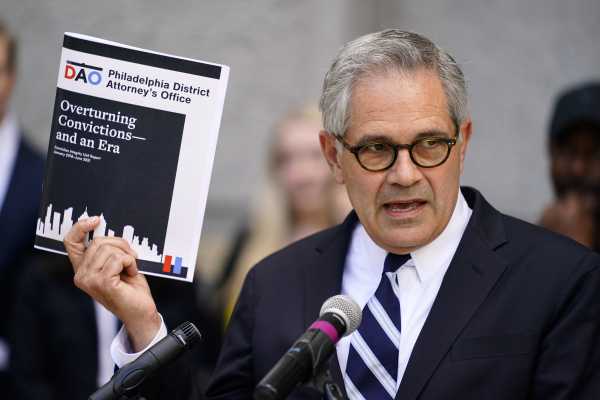

Krasner, who was first elected in 2017, was one of the first people to run as a self-described “progressive prosecutor” — part of a growing national movement of candidates who emphasize that the discretionary decisions made by a city’s chief attorney can have a profound effect on mass incarceration.

Since taking office, Krasner has stopped seeking cash bail for some low-level offenses, a move to reduce jail time that some defendants have to serve simply because they’re low-income. His team also stopped prosecuting marijuana cases and most prostitution cases against sex workers, and heavily deprioritized retail theft — something that’s been on the rise in the city over the past two years. His office touts statistics on his website that Krasner has imposed over 29,000 fewer years of incarceration compared to the previous district attorney.

Amid rising crime rates and increasing concern about crime, a growing backlash, led primarily though not exclusively by Republicans, has depicted reformers like Krasner and Boudin as threats to public safety. Researchers have not found a link between progressive prosecutors and local crime rates, and in fact found that declining to prosecute a misdemeanor can significantly reduce the likelihood of future crime.

If more DAs like Boudin and Krasner are booted out of office, reformers fear other prosecutors may lose interest in bucking old “tough on crime” playbooks.

While some of Philadelphia’s crime uptick began prior to Krasner taking office, the situation has gotten worse since the pandemic. Philadelphia’s murder rate went up 58 percent between 2019 and 2021. There were a record 499 homicide victims in 2020, followed by another record-breaking 562 homicides in 2021. The number of murders this year — 409 as of October 3 — is slightly less than this time last year, but still the second-highest the city has seen by this date in 15 years.

Gun violence has also been increasing statewide and nationally since the pandemic started, including in suburban and rural areas. One analysis from the Council on Criminal Justice, a research and policy group, found a 30 percent increase in homicides across 34 US cities in 2020 compared to 2019, and another independent crime analysis found murder up 37 percent across 57 localities.

Jane Roh, a spokesperson for Krasner, noted that of the five largest cities in Pennsylvania, Philadelphia’s increase was similar to Pittsburgh (where homicides were up 53 percent) and smaller than Reading (117 percent) and Allentown (71 percent). Compared to the other 12 Pennsylvania counties of at least 300,000 residents, Philadelphia’s increase ranked sixth.

Still, the level of violence is hard to hand-wave away with comparative statistics, and because Philadelphia is so large, percentage increases can obscure what are many, many more deaths. Just last week, five high schoolers in Philadelphia were shot, one fatally, after an afternoon football scrimmage, and other crime, like carjackings, has spiked.

Critics of the district attorney allege that his policies have contributed to the rise in crime by sending a message that laws in the city won’t be enforced. They point to declines in conviction rates for illegal gun possession: Between 2015 and 2020, the share of illegal gun possession cases resulting in conviction fell from 65 percent to 42 percent, a decline driven primarily by cases being dismissed by judges and withdrawn by the district attorney. The district attorney said that some offenders went through diversion programs instead of facing jail time and that police brought forward weak cases that were too difficult to win in court.

Krasner’s supporters stress that the lagging performance of police should get more attention. From January 1, 2017, through September 18, 2022, Philadelphia police made arrests in less than 40 percent of homicide incidents in the city and just 18 percent of nonfatal shootings. The district attorney cannot charge those who have not been arrested.

Krasner has argued more energy should be focused on improving the low clearance rate for shooting cases rather than on trying to remove illegal guns from the streets. (In February, the Philadelphia Police Department launched a new division focused on investigating nonfatal shootings.) Roh, Krasner’s spokesperson, also noted that the DA supports a host of enhanced gun safety regulations, measures opposed by Republicans on the state level.

Even amid the rise in crime, Krasner easily won his reelection in 2021, earning more than twice as many votes as his Republican challenger, Chuck Peruto — who campaigned on getting tougher on crime. While Krasner faced a heated primary, beating a prosecutor backed by the city’s police union, he barely campaigned in the general election against Peruto and declined to debate him. Democrats outnumber Republicans in Philadelphia seven to one, and the city hasn’t had a Republican DA in over three decades.

Krasner has been a target of attacks for Pennsylvania Republicans for the last half-decade, but the impeachment inquiry is a new escalation. The investigation began in June after three House lawmakers who live in districts far from Philadelphia circulated a memo seeking their colleagues’ support for impeaching Krasner for “dereliction of duty.”

About two weeks later, 110 Republicans and four Democrats in the Pennsylvania House voted against 86 Democrats to establish the committee, which has subpoena power. In July, Pennsylvania’s Republican House speaker appointed five members to the committee, including two Philadelphia Democrats who had voted against the inquiry; one, Danilo Burgos, told the Philadelphia Inquirer he only agreed because he was told they’d be investigating crime statewide. But Republican lawmakers voted against an amendment supported by Democrats that would have expanded the committee’s scope to study statewide violence.

Michael Straub, a spokesperson for Pennsylvania’s House speaker, defended the narrow focus. “I mean, Philadelphia is such a crucial place in the state,” he told Vox. “So much of what makes Philadelphia relevant to the rest of the country and rest of the world is its population and culture, so making sure Philadelphia is safe and vibrant and attracting people is important to everyone regardless of political party.”

Republicans are now trying to claim this is not necessarily about impeachment

Despite the unambiguous origins of the committee, Republicans are now claiming that their work should not be assumed to be about impeachment. The committee “has a wide-ranging scope and is much broader than a mere impeachment inquiry,” said Jason Gottesman, House Republican caucus spokesperson, when Vox asked about the anti-democratic implications of the probe.

Unlike other states, Pennsylvania voters cannot recall elected officials, and there have been only two successful impeachments in state history — a state supreme court justice in 1994 and a district judge in 1881. The state constitution says “the Governor and all other civil officers shall be liable to impeachment for any misbehavior in office,” although Krasner’s office argues this language applies only to elected state officials, not local politicians.

Some reports have suggested the “any misbehavior in office” language is vague enough to include general discontent with how an official approaches their job. Bruce Ledewitz, a Duquesne University law professor who teaches a course on the Pennsylvania Constitution, told Vox that the select committee would need to find actual evidence of corruption or misbehavior to impeach Krasner. Simply disagreeing with his policies would not be enough.

“The idea that the constitutional language is so broad that it could mean anything, I don’t think that’s the case,” Ledewitz said, pointing to the statutory removal provisions, and contrasted them with the looser standards of impeachment at the federal level. If the Pennsylvania legislature does move to impeach Krasner, Ledewitz said they’ll need to prepare for it to be challenged in court, like it was in Pennsylvania in 1994.

In August, the select committee issued its first subpoena of Krasner, requesting documents related to his policies including on bail and plea bargains. They also asked for documents on prosecuting police officers, and the “complete case file” of Ryan Pownall, a former Philadelphia police officer who faces third-degree murder charges for killing a Black man in 2017. Pownall is set to go on trial in November.

Krasner allies say the select committee’s interest in these case files reveals they are more interested in shielding police from accountability than protecting victims of crime. Vox asked the Republican chair of the select committee, Rep. John Lawrence, why these documents were being prioritized in the investigation. Gottesman, answering on Lawrence’s behalf, pointed to three press releases from Lawrence that did not directly address the question.

In a letter sent to the committee in August, Krasner’s lawyers asked the committee to withdraw their requests and end the investigation, and later petitioned a state court for relief. They argued in legal filings that the probe is illegitimate because it serves no proper legislative purpose and Krasner has committed no impeachable offense. They also said that impeaching Krasner would violate the constitutional rights of the Philadelphia voters who elected him, that documents for the pending Pownall trial are privileged, and that it would be illegal to disclose grand jury materials.

The select committee — which asked for the “complete case file” of a pending murder trial, including documents “related or referring to the investigative grand jury proceedings” — denies it sought any privileged materials. The committee’s interim report issued September 13 noted that the district attorney’s office could withhold privileged materials if it provided a list of them.

Krasner’s lawyer, Michael Satin, told Vox that they would not produce such a log when the request was “patently improper” and an abuse of power by the legislature. “Courts, not legislative bodies, are best equipped to resolve disputes involving a subpoena, especially one that involves an inquiry into a pending criminal case,” said Satin. The select committee has asked Krasner at least twice in writing to withdraw their court petition.

But state lawmakers — including Democrats opposed generally to the impeachment inquiry — were not happy that Krasner resisted the legislature’s subpoena and voted 162-32 to hold him in contempt. Republicans like Rep. Lawrence claimed Krasner “willfully neglected” the subpoena, though Krasner’s team pushed back, saying they followed the law by registering their objection with the judiciary, in addition to writing their objections to the committee.

Rep. Jared Solomon, a Democratic state rep from Northeast Philadelphia, told the Philadelphia Inquirer he saw Krasner’s resistance as “exactly the same” as Steve Bannon, who was convicted of contempt for failing to comply with congressional subpoenas into the January 6 investigation.

About a week after the contempt vote, Krasner’s team began providing some records to the select committee — primarily those that were already available online on their website. If Krasner’s team had provided those documents to the committee initially and only objected to the files related to the pending murder trial, it’s unlikely as many Democrats would have held the district attorney in contempt, but Krasner’s team didn’t want to grant legitimacy to what they saw as a sham investigation.

“This impeachment investigation is absolutely just a witch hunt. I’m on the judiciary committee and I have voted at every instance to not proceed with this, but I’m a lawyer and so is District Attorney Krasner, and legal subpoenas are legal subpoenas,” said Rep. Emily Kinkead (D-Pittsburgh), who voted to hold Krasner in contempt. “While I understand everything the legislature does is inherently political, we have the right to issue subpoenas and if he believed there were privileged items that were requested, he should have created a privileged log, to say, ‘These documents exist but you’re not entitled to see them,’ but he didn’t even do that.”

Impeachment looks less likely in the Senate than in the House

In order to impeach, a majority of members in the Republican-controlled House would need to vote in favor, and then two-thirds of the state Senate would need to, too. That means 34 senators would need to vote in favor of impeachment, and there are 28 Republicans currently in the chamber.

Despite dozens of Democrats voting to hold Krasner in contempt, it still might be hard to get six on board for impeachment, especially when the specter of Republicans trying to throw out Philly votes two years ago still looms so large.

“Bad things happen in Philadelphia,” Trump proclaimed in the fall of 2020, in an attempt to gin up distrust about election integrity in Pennsylvania’s biggest city. Following the 2020 election, Trump put on blast a Republican election commissioner from Philadelphia who found no evidence of voter fraud, insisting “he refuses to look at a mountain of corruption & dishonesty.”

Krasner performed especially well in his reelection campaign in areas with high levels of gun violence, giving the district attorney confidence to say his progressive policies were backed by a mandate from the people most affected.

Progressive allies of Krasner have been organizing over the past few weeks to send a message to Democratic state officials that voting to impeach Krasner would be aligning themselves with Republican election deniers.

“We’re not just going to roll over and pretend that there’s not an attack on Philadelphia, on Black and brown people,” said Tonya Bah, a Philadelphia activist who leads Free the Ballot. “For Democrats to side with Republican leadership to harm someone that we elected, it is very disheartening, and quite frankly, we have to draw a line in the sand.”

On September 23, the Working Families Party, a union-backed group that helps elect progressive candidates locally and nationally, announced it would be rescinding five midterm endorsements of Democratic state reps who had voted to hold Krasner in contempt.

Vox contacted the five Democrats who lost their WFP endorsements. Two elected officials from Pittsburgh — Reps. Jessica Benham and Emily Kinkead — said they didn’t even know they had received the WFP endorsement but were not planning to vote for impeachment.

“I voted to hold the DA in contempt because legislative bodies have jurisdiction to issue and enforce their own subpoenas,” Benham said. “That the DA responded in part to the subpoena after the contempt vote, which carried no actual penalty, demonstrates that he could have responded in part prior to that vote, but chose not to for reasons unclear. Nevertheless, I will be voting against impeachment if that charge comes before the House, as I respect the will of the voters.”

Rep. Danielle Friel Otten of Chester County also said she views her subpoena vote as very different from any vote to remove someone from office. “For me, the vote to find DA Krasner in contempt of the House was about equal application of the law,” she told Vox. “This was a procedural vote about responding to a lawfully issued subpoena. Larry Krasner was duly elected by the voters of Philadelphia, and impeachment requires a high bar. To this point, I’ve seen no evidence of any impeachable offense.”

Vanessa Clifford, the mid-Atlantic political director for the Working Families Party, told Vox both Benham and Kinkead had submitted candidate questionnaires applying for WFP’s endorsement, and were both personally notified that their state committee had endorsed their reelection campaigns.

Rep. Rick Krajewski, a Democratic state House lawmaker representing West Philadelphia who voted against holding Krasner in contempt and was disappointed by the nine Philadelphia state reps who did, said Krasner is an easier “punching bag target” than, say, local judges, because there’s only one of him. Pinning the city’s problems on the district attorney is also easier for state Republicans to do than investing in Philadelphia communities, schools, workers, and parks and recreation.

There’s no doubt that Philadelphia has real issues with people feeling safe, Krajewski added. “But as a result, we’re seeing a return to ‘tough on crime’ rhetoric, to overpolicing, and in my opinion, that is the wrong response to this moment,” he said. “We’ve seen that during the Reagan era, the Nixon era, an investment in crackdown does not work. I think for myself and other Democrats who support Larry, we’re having real conversations with our community about what this could mean for our democracy and how we can stand united.”

Our goal this month

Now is not the time for paywalls. Now is the time to point out what’s hidden in plain sight (for instance, the hundreds of election deniers on ballots across the country), clearly explain the answers to voters’ questions, and give people the tools they need to be active participants in America’s democracy. Reader gifts help keep our well-sourced, research-driven explanatory journalism free for everyone. By the end of September, we’re aiming to add 5,000 new financial contributors to our community of Vox supporters. Will you help us reach our goal by making a gift today?

Sourse: vox.com