Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

At any point in the day, I can open my closet, pull out a swimsuit, squeeze into it, pose for a selfie in my full-length mirror, and broadcast the image to the world. It’s easy to take for granted just how much the Internet has democratized the thirst trap; with social media, we can each be a part-time model and beach bunny for all seasons. But when I was growing up, in the early two-thousands, the only photographs of young women in bathing suits which I regularly saw were in the summer issues of the teen magazines that arrived on my doorstep. The bikini-clad models on those pages were impossibly thin; they were also, with rare exceptions, white. It was only in 1997 that Sports Illustrated featured a solo Black model on the cover of its iconic swimsuit issue, with Tyra Banks baring her washboard abs and breasts that nearly spill out of her top, in a red-and-pink polka-dot two-piece. So much for representation.

In those days, I knew of only one way that a mere mortal could be pictured in a bikini for paying subscribers. It was to submit a picture to Jet, a weekly magazine for Black news and entertainment. Each issue included an ad for “beautiful models between the ages of 18-25,” along with instructions to fill out a “coupon” with contact information and “a current snapshot of yourself in a bathing suit.” If the magazine liked your photograph, they would connect you with a professional photographer. From Jet’s inception, in 1951, until the magazine ceased its print operation, in 2014, it published pictures of these women in a column called “Beauty of the Week.” “Every issue of the magazine showcases one of the country’s most beautiful, shapely and radiant Nubian princesses,” Jet boasted, referring to the ordinary women of extraordinary confidence—nurses, paralegals, college students, post-office workers who posed for the magazine. Though the text was essentially decorative, their professions were noted, alongside their hobbies. In Paul Beatty’s “The Sellout,” the narrator’s mother was a Jet Beauty of the Week, and all he knows about her is what was included in the small text alongside her “curvy expanse of thighs and lip gloss”; namely, that she was a student from Key Biscayne “who enjoys biking, photography and poetry.”

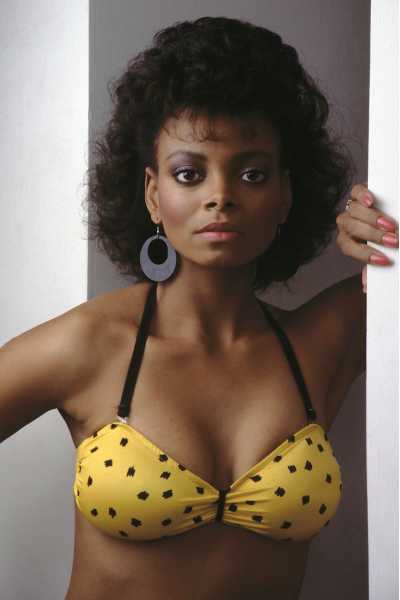

Treva.

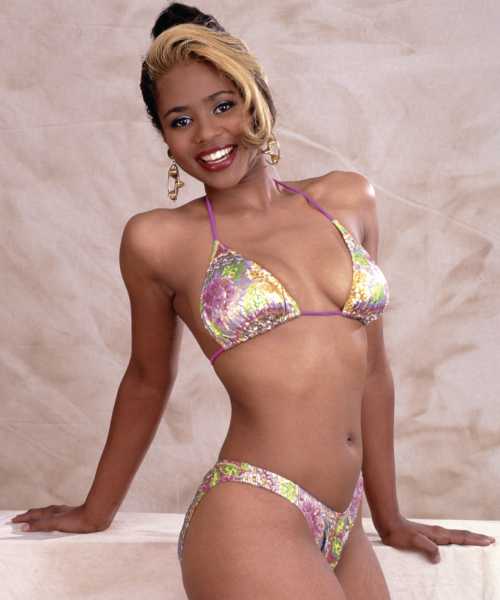

Brandy.

Lynette.

In an essay, the filmmaker Malcolm D. Lee (“The Best Man,” “Girls Trip”) recalled ripping out the Jet “Beauty of the Week” page and putting it up in his locker. His white private-school classmates gave him grief. They “would say, ‘They’re fat.’ I was like, ‘What are you talking about? That was when I started to understand the different standards of beauty,’ ” Lee wrote. The women who graced page 43 (the “Beauty of the Week” column was typically on page 43) were thin, but curvier than a typical model, and, for decades, their measurements—almost always hourglass—were listed alongside their photos. On their bodies, you could spot faded stretch marks, on their teeth lipstick stains, on their faces an endearing “Am I doing this right?” expression. They kept their wedding rings on. These were real women, not fantasies. Former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick’s mother—a part-time shopgirl at Saks Fifth Avenue—was a Jet Beauty of the Week (she borrowed clothes from work for the shoot).

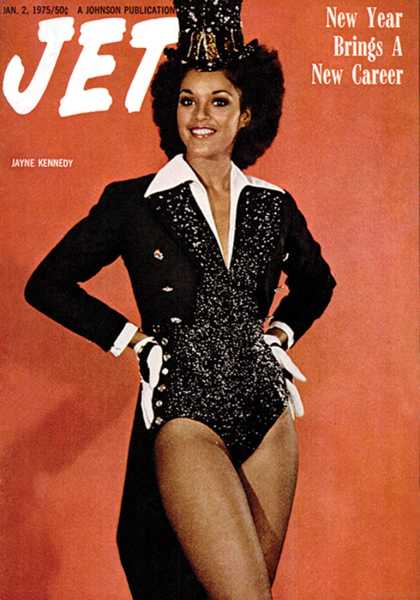

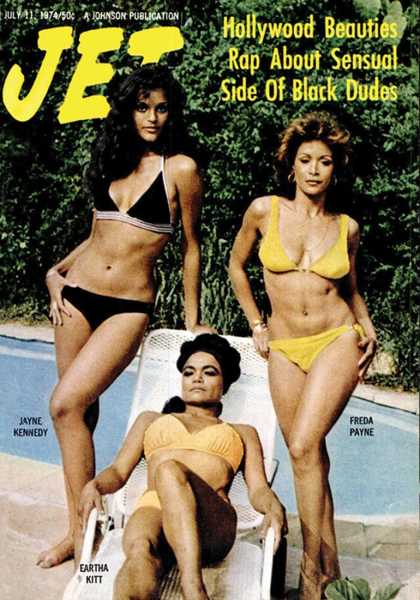

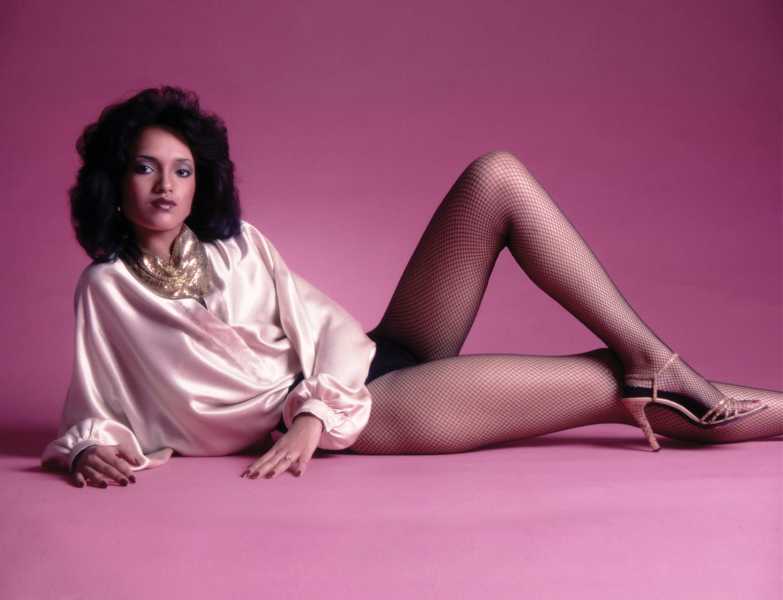

Adrienne.

A new book, “Black Is Beautiful: JET Beauties of the Week” (powerHouse Books), collects some of the pictures that LaMonte McLemore, a vocalist and a founding member for the psychedelic soul band the 5th Dimension, took for Jet in the forty-plus years he worked for the magazine as a freelance photographer. Jet, which had more than a million subscribers, was the saucy little sister of Ebony. Both magazines were part of the publishing tycoon (and fashion mogul) John H. Johnson’s Chicago-based Black media empire. Ebony launched, in 1945, as an African American answer to Life magazine, catering to the tastes of upwardly mobile Black readers. Jet was less buttoned up. In 1975, the magazine published an interview with Pam Grier on the subject of how “it takes more than one man to satisfy [her],” plus an update on her rumored romance with Freddie Prinze. Jet did not feel the need to present a prudish image of Black people to counteract white stereotypes about their hypersexuality. Jet was for Black people who wanted to look at other Black people. In fact, one of its best-known rubrics was a listing of every time a Black character was going to appear on television week by week. Jet was also not like the respectable Ebony, but it was still respected, especially when, in 1955, it became the first outlet to publish the open-casket photographs of Emmett Till. McLemore, the first African American photographer hired by Harper’s Bazaar, was so proud to have his name associated with Jet that he squeezed in “Beauty of the Week” shoots between 5th Dimension tour stops.

There was an amateurish chaos to the “Beauty of the Week” photos that made them feel charged with erotic possibility. These were “around the way” girls, as the LL Cool J song goes. (The rapper wrote in his 1997 memoir, “I Make My Own Rules,” that he decorated his childhood bedroom with “posters of Bruce Lee and, later, Run-D.M.C. and Jet magazine’s Beauty of the Week.”) They looked like someone whom you might catch a glimpse of at the Jersey Shore one day. “Hey, did I see you in Jet?” was a pickup line someone once tried on my aunt.

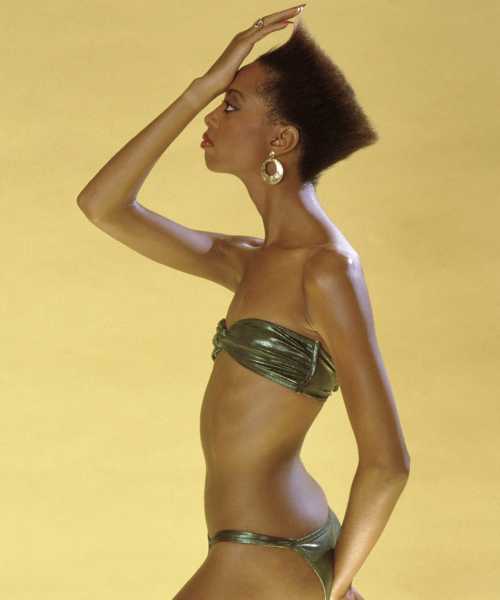

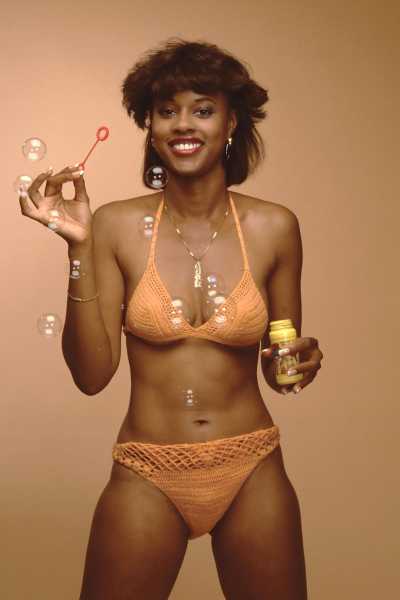

Though a professional photographer, McLemore knew to make the images look as natural as the beauties he was tasked with shooting. In one of his photos, a woman named Darolyn, clad in a red bikini and matching leg warmers, opts for an asymmetrical pose that makes her chest look lopsided. Another woman named Karen, wearing a gold necklace spelling out her name and a peach crochet bikini, blows soap bubbles from a plastic bottle of the kind I remember buying at the local dollar store in the summer months.

Karen.

Hanaiya.

Joycelyn.

Darolyn.

Many of the women were self-styled, donning the sultrier version of their Sunday best. In one photo, a woman named Denise pairs a tiger-print bikini with costume jewelry and pink acrylic nails. Tasha, whose hobby is listed as skydiving, has applied metallic silver eyeshadow that clashes with her gold earrings and matching bikini. When Jet did shoot professional models or actresses for the column, the women were still relatively dressed down. In 1971, years before Grier made the gossip pages of Jet or landed her signature roles in Blaxploitation films, she was an up-and-coming actress who posed for the “Beauty of the Week” column at the urging of her team. She later reflected on the image for ESPN’s Andscape blog, complaining about the shoot’s lack of niceties: “I was ashy, no makeup, my hair was all over the place. I didn’t even have polish on my toenails or my fingernails, c’mon.”

Denise.

Tasha.

But the lack of polish was what gave Jet Beauties of the Week their special charm. By now, we are all too schooled in the art of posing to reproduce the effect. In the age of the smartphone camera, most of us know our good angles. We can blur away our imperfections using an Instagram filter. The raw appeal of Jet’s erstwhile models remains unrivalled. “Black Is Beautiful” captures the quality that made these women most appealing—their confidence that anyone with eyes would want to look at them, au naturel.

Peaches.

Sourse: newyorker.com