Last week, while the political world was transfixed on Virginia, something arguably more consequential took place in the state just south of it: North Carolina’s Republican-controlled statehouse passed new political maps based on the 2020 census that give the GOP a significant leg up in congressional elections.

In a state split nearly evenly between Republicans and Democrats — Trump won it in 2020 with 49.9 percent of the vote — the new map of districts for House elections would likely give the GOP at least 10 House seats out of 14 (71 percent). North Carolina law does not allow Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper to veto the maps, which means they will be used in 2022 unless courts intervene.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project, an academic group that grades political maps based on a set of mathematical metrics of fairness, gave the North Carolina map an “F” for extreme partisan bias — marking it as one of the very worst proposals anywhere in the country. Two separate analyses, from a Duke University professor and the Campaign Legal Center, also found that the map was unusually tilted in the GOP’s direction.

“Ten years ago, North Carolina’s legislature drew an extremely gerrymandered congressional map. It was so gerrymandered that they were ordered to redraw it. Twice,” says Will Adler, an expert on gerrymandering at the Center for Democracy and Technology think tank. “This map appears to be at least as extreme as the ones drawn in the last cycle.”

Whether North Carolina’s newly passed maps will survive legal review — the activist group Common Cause has already filed a suit to stop them — remains to be seen. But challenges to the map face an uphill climb: a 2019 Supreme Court ruling defanged federal anti-gerrymandering protections, making it easier for North Carolina Republicans to get away with twisting the maps.

In recent years, North Carolina’s Republican legislative majority has been on the cutting edge of anti-democratic activity — going further than other legislatures and even pioneering new tactics for cementing their hold on power that have been picked up by Republicans elsewhere. What happens there is a leading indicator of where our political system is heading.

That’s why this isn’t just about one hyperpartisan statehouse. As states across the country draw new lines in the wake of the census, governments controlled by a single party have a once-in-a-decade opportunity to give themselves a massive leg up. While some Democratic-controlled legislatures like Illinois are abusing this power, Republicans are both better equipped and have proven more willing to draw undemocratic lines that favor themselves.

The GOP’s ruthless redistricting is part of an even bigger pattern of state-level sabotage of democracy. Gerrymandering is one tool the GOP uses, together with voter suppression bills and institutional power grabs, to tilt the electoral playing field toward their side.

Given the key role states play in setting the rules for national elections, this represents an existential threat to our political system. If American democracy dies, it’ll die in the states.

Why North Carolina’s new maps are so unfair

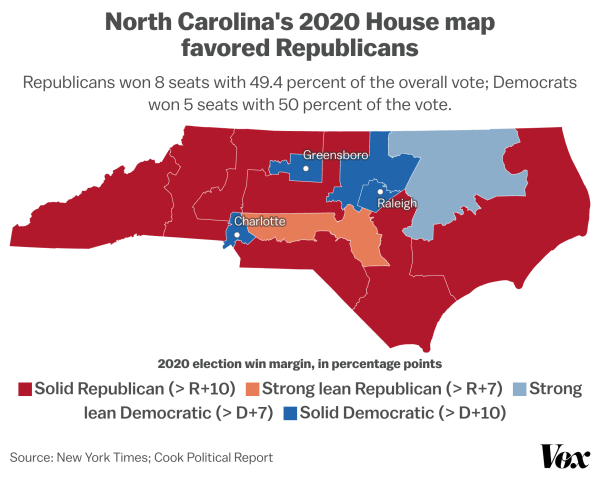

To get a good baseline for what happened in North Carolina, it helps to start with the 2020 House election results. Using a map drawn in accordance with court rulings against the gerrymandered map used in 2018, Republicans still won eight of 13 House seats despite Democratic candidates receiving slightly more votes overall.

This result, as you can see in the map below, reflects differences in where Democratic and Republican voters live. Because Democrats are concentrated in and around cities like Charlotte and Greensboro, while Republicans are more spread out across the state, even more neutral maps can yield some degree of GOP advantage.

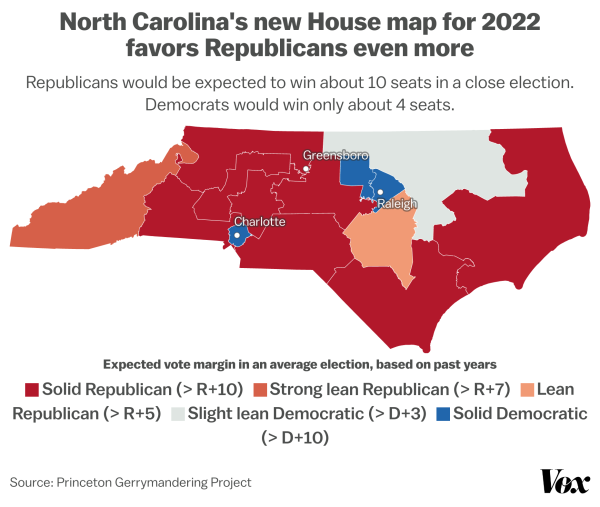

But now take a look at how a similarly close election would play out under the proposed 2022 map, which has one more seat thanks to North Carolina’s population growth.

Instead of winning eight seats, Republicans win about 10 — a degree of advantage that can’t only be explained by Democrats clustering in cities.

The new map reflects the twin hallmarks of any gerrymander, called “packing” and “cracking.” Gerrymanders work by concentrating a large number of the opposing party’s voters in a handful of districts (“packing”), while spreading out the rest of their supporters across districts where they’re consistently outnumbered (“cracking”).

The new map’s lines are drawn in strange ways in order to pack and crack Democratic voters. Democrats in Charlotte, for example, are packed in a very small district where they outnumber Republicans by a roughly 3 to 1 margin. By contrast, Greensboro and the nearby area is cracked in such a way as to create several different districts with comfortable Republican majorities.

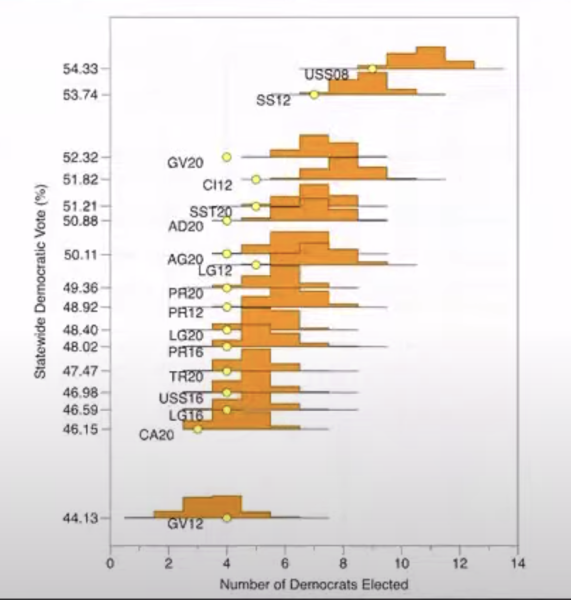

One way to measure the degree of unfairness is to look at what gerrymandering experts call “responsiveness”: the extent to which the outcome of elections changes based on shifts in votes. Duke mathematician Jonathan Mattingly ran an analysis of the new maps testing their responsiveness, looking at how many seats each party would get using statewide popular vote totals from previous elections (e.g., the Democrats’ US Senate win in 2008, the GOP’s gubernatorial victory in 2012).

The following chart shows his results. The orange blocks show the frequency of different House outcomes under various hypothetical maps, with the peaks representing the most common vote outcomes. The yellow dots show the outcome using the map Republicans just passed.

In the hypothetical maps, Democrats generally do better as they start winning bigger and bigger majorities — depicted by the orange peaks shifting to the right. But for the 2022 map’s yellow dots, that’s not the case: Republicans continue to maintain a 10-4 advantage even when Democrats win solid statewide majorities.

It would take an absolute blowout, over 7 percentage points in the statewide popular vote, for Democrats to even get half of the state’s congressional delegation.

The Princeton Gerrymandering Project did a similar exercise, running over a million simulations of various possible maps. In the vast majority of these maps, Democrats average six or seven seats in House elections — half or a little under the total. Under the new Republican-drawn map, Democrats average just four.

The size of this GOP advantage in the new map, the consistency of its wins with different vote totals, and the lines of the districts themselves are all very strong evidence of an extreme partisan gerrymander.

“All the political scientists are sort of coming to the same conclusion: this doesn’t look happenstance. It looks planned,” says Adam Podowitz-Thomas, a senior legal strategist on the Princeton team.

North Carolina and the state-level threat to democracy

The North Carolina gerrymander, on its own, doesn’t guarantee that Republicans control Congress. On net, it’s likely to shift two or three House seats into the GOP’s column in 2022 — a nice advantage, especially given how closely divided Congress is at present, but not an insurmountable one.

The issue is that, across the country and over the last few years, Republicans have been systematically more willing and able to redraw lines in their favor than Democrats. An analysis of the past three elections, conducted over the summer by the Associated Press, found that gerrymandering has given Republicans “a greater political advantage in more states than either party had in the past 50 years.”

This GOP advantage is likely to increase in the current redistricting cycle. In the 2020 elections, Republicans swept key statehouse races in states where legislatures control redistricting — North Carolina, obviously, but also Florida, Texas, and Georgia. All four are larger states, so a lot of seats are in play. They’re also all fairly competitive, which means that there are more Democrats to pack-and-crack into political oblivion than there are in a deep-red state like Alabama.

Some Democratic state legislatures appear willing to play the same game in 2021. The new Oregon and Illinois maps appear to be heavily biased in Democrats’ favor; New York’s map, while not yet released, may come out quite tilted to the left.

But in recent history, Democratic-controlled states have been less likely to engage in extreme gerrymandering than their Republican peers. And even if Democrats wanted to totally change that in 2021, they couldn’t: The party just doesn’t have enough power in enough states. Some of the large states Democrats control, like California and Virginia, have delegated redistricting to independent commissions.

The asymmetry in gerrymandering speaks to a deeper difference between the parties. Republicans are more willing to rewrite the rules of the political game in their favor than Democrats — to undermine foundations of the democratic system in order to cement their hold on power.

In this sense, North Carolina’s gerrymandering is less an undemocratic one-off than part of a bigger pattern of undemocratic behavior.

You have election subversion laws, like Georgia’s SB 202, that give state Republicans the power to seize control of the actual vote-counting procedure in counties. You have post-2020 efforts to replace election administration officials who blocked Trump’s efforts to steal the election, like Georgia’s Brad Raffensperger or Michigan’s Aaron Van Langevelde.

You have power grabs, as seen in states like North Carolina in 2016 and Wisconsin in 2018, where Republican legislatures strip newly elected Democratic governors of their authority. You have a number of laws aimed at suppressing turnout in Democratic-leaning communities, ranging from strict voter ID requirements to voter roll purges to restrictions on mail-in ballots.

Underneath it all is the Republican Party’s delegitimization of democratic rule and embrace of Trump’s lies about election fraud.

In a 2021 working paper, the University of Washington’s Jake Grumbach attempted to quantitatively measure the health of democracy in all 50 states — and to figure out what correlated with its declines in certain places. He found that Republican control over state government — and only Republican control — is strongly correlated with large and measurable downturns in democracy.

“Results suggest a minimal role for all factors except Republican control of state government, which dramatically reduces states’ democratic performance,” he writes.

North Carolina is one of the key examples in Grumbach’s paper: Its democracy score starts to plunge in 2011, the last time Republicans had control of the redistricting process. The maps they came up with that time were struck down in courts; there’s already a case pending about the new maps.

But there’s no guarantee the outcome will be the same. In the 2019 case Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal judiciary does not have the power to block unfair partisan gerrymanders. Rucho is one in a series of recent Supreme Court cases gutting voting rights protections, which have made it much easier for state legislatures to get away with extreme gerrymanders. Similarly, Republicans in Congress, in thrall to Trump, have become more willing to engage in anti-democratic practices — culminating with the events of January 6.

This broad-spectrum Republican turn against democracy does not mean that the American political system is doomed. But what happened in North Carolina last week should remind us that we are in the midst of a rolling political crisis — the authoritarian radicalization of one of our two major parties.

Will you support Vox’s explanatory journalism?

Millions turn to Vox to understand what’s happening in the news. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower through understanding. Financial contributions from our readers are a critical part of supporting our resource-intensive work and help us keep our journalism free for all. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today to help us keep our work free for all.

Sourse: vox.com