This story is part of a group of stories called

Uncovering and explaining how our digital world is changing — and changing us.

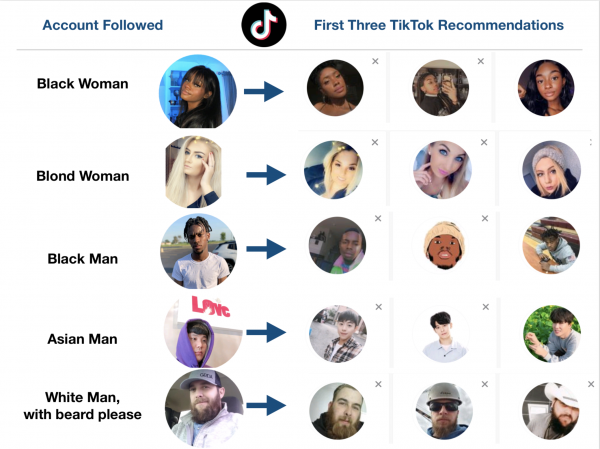

When artificial intelligence researcher Marc Faddoul joined TikTok a few days ago, he saw something concerning: When he followed a new account, the profiles recommended by TikTok seemed eerily, physically similar to the profile picture of the first account. Following a young-looking blond woman, for instance, yielded recommendations to follow more young-looking blond women.

Faddoul, a research scientist at the University of California Berkeley, wanted to look into how TikTok, a China-based social media platform popular among teenagers, worked. So he started with a fresh account, not linked to profiles on any other platforms. And as he followed various accounts, Faddoul observed that the profile pictures of the recommended accounts seemed very similar to the profile image of the initial account.

Following black men led to recommendations to follow more black men. Following white men with beards produced recommendations for more white men with beards. Following elderly people spawned recommendations for other elderly people. And on and on.

Faddoul’s TikTok experiment wasn’t a scientific study. It simply represents one individual researcher’s initial experience on the platform. Recode reviewed screenshots sent by Faddoul and conducted some of the same searches that he did. Those searches produced similar results: recommended follows tended to physically resemble the initial account followed, though they were not always the exact same accounts that appeared in Faddoul’s results.

Recode also followed some other randomly selected accounts, but those didn’t necessarily produce recommendations that shared one easily observable identity. There were sometimes similarities in the account followed and those recommended, but those trains weren’t obviously physical. Instead, the recommended accounts all shared an interest, like Broadway musicals, the outdoors, or pets.

It’s worth noting that at least one other person, commenting on the Twitter thread in which Faddoul originally posted his results, said they were not able to replicate his results. But Faddoul’s experience nevertheless raises the question of how these recommendation engines work on social media platforms. When you follow someone with certain demographic traits, why might you get recommended people with those same physical identifiers? And how does this affect people’s experiences on social media?

Platforms often try to build recommendation algorithms that will produce results that match your interests. But these recommendations can have unintended consequences and can create concerns about so-called filter bubbles. (A filter bubble is the result of highly personalized internet content that leads to a sense of isolation.) If you only follow people on social media who look like you or share your interests, for instance, you stand to get stuck in an endless feedback loop that could distort your worldview. If Faddoul’s experience is representative of most people on the platform, TikTok might be enabling the same problem that has plagued other, older social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook.

TikTok pushed back against Faddoul’s findings.

“We haven’t been able to replicate results similar to these claims,” said a TikTok spokesperson. “Our recommendation of accounts to follow is based on user behavior: users who follow account A also follow account B, so if you follow A you are likely to also want to follow B.”

This process is commonly known as collaborative filtering, a type of recommendation algorithm that can also pop up on dating apps. The way this type of algorithm works might explain his results. Faddoul was quick to admit that collaborative filtering might be at play.

“What collaborative filtering does is that if I follow an account, it’s going to look at all the other people who followed that same account,” Faddoul explained. “And the algorithm is going to select the accounts for which [there is] a lot of overlap between the users that have followed this account that I just followed.”

However, Faddoul also told Recode that he believes it’s more likely that TikTok is using something he calls automatic featurization. This type of recommendation algorithm could take “signals” from profile images to find profile pictures with similar attributes. These kinds of signals would be correlations between the pictures, which could correspond to anything from skin color to having a beard. The algorithm is simply looking for similarities in the photos or profiles. It’s worth noting that in our searches, Recode found plenty of recommendations that had no physical resemblance to the initial account followed.

“What I suspect is happening is that TikTok is featurizing the profile picture,” he says, “and using these features in the recommendation engine.”

But regardless of how results like these show up, a more general problem with recommendation algorithms is that they can ultimately confirm our preexisting biases.

“Recommendation engines tend to create selective information environments,” Faddoul told Recode. “In the case of TikTok, it’s a little bit different, because people are not necessarily looking for information.”

He also points out that such a system could create a problematic feedback loop. If the most followed influencers tend to be white, and those who are recommended after following a white influencer are also white, it could shut off creators who are people of color.

Curious about how that might work? Last year, a team supported by Mozilla created an online game called “Monster Match,” which shows how your initial preferences can narrow the results you see down the line. You can play the game for yourself.

Recommendation algorithms on social media have long been controversial. We rarely know how they work, and their results can be confusing and sometimes even creepy. Take Facebook’s People You May Know feature, a sidebar on the platform that suggests people you might want to be friends with. As Gizmodo reported two years ago, that appears to rely on all sorts of data collected from users to predict potential connections. But the system doesn’t always recommend people you actually know — or at least, it is unclear how you may be connected. Sometimes, it can recommend people we’d rather not know, like the patients of the same psychiatrist.

There’s no evidence yet that there’s anything nefarious at play in TikTok’s recommendation algorithm. But Faddoul’s results are strange. They’re also a reminder that we often know little about how the algorithms behind the scenes on our favorite tech platforms recommend other content and that they can end up confirming our biases more often than we’d like to think.

Open Sourced is made possible by Omidyar Network. All Open Sourced content is editorially independent and produced by our journalists.

Sourse: vox.com