This spring, Jeopardy champion James Holzhauer showed America just how much the perfect combination of intelligence and skill can look like cheating. The analytically minded professional gambler “broke” the game by finding the mathematically optimal way to play—prioritizing hard questions and betting big—perhaps forever changing Jeopardy. This isn’t the first time a quiz show blurred the line between merit and unfair advantage. Before Holzhauer, there was Charles Van Doren, who died in April of this year, and whose rise and fall as a quiz show champion in the mid-1950s is depicted in the Robert Redford-directed Quiz Show, released 25 years ago this fall.

The 1950s and ’60s brought an expansion of opportunity and inclusivity in American institutions, the broadened availability of education and employment for people who weren’t upper-class white men. One such person was Herbert Stempel.

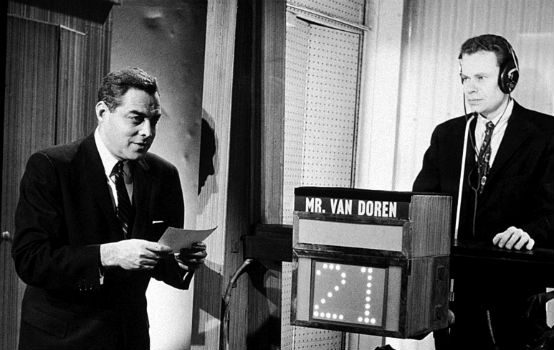

America met Stempel on the NBC quiz show Twenty-One at 10:30 pm on Wednesday, October 17, 1956. The show’s host (“quizmaster”) Jack Barry introduced him as a lower-class boy from Brooklyn who, despite his poverty and Jewish heritage, got his break thanks to the GI Bill, which made it possible for him to attend City College after eight years of military service. Stepping into the show’s trademark soundproof booth to answer questions, Stempel looked awkward, moving stiffly and sweating through a too-tight shirt, and he spoke haltingly (in Quiz Show John Turturro captures Stempel’s neurotic charm). It was abundantly clear to the audience that Herbie Stempel was not born and bred among America’s elite, but his appearance on television offered a chance to win fame and fortune by his brainpower alone.

Advertisement

Stempel’s big opportunity came at a time when TV quiz shows were the ultimate symbol of midcentury optimism, of expanding opportunity to join the middle and upper classes. CBS revolutionized the genre in 1955 with The $64,000 Question by offering prizes several orders of magnitude larger than previous quiz shows. The radio quiz show Information, Please! (1938-1951) never offered winnings larger than $25 and a complete set of the Encyclopedia Britannica. The Question’s large winnings represented real opportunity for upward mobility, and the possibility of multi-week winning streaks meant audiences could get to know successful contestants. The new format caught the zeitgeist. Columnist Max Lerner referred to CBS’s quiz show as “Huey Long’s ‘Every Man a King’ put into TV language.” The Nation’s Dan Wakefield joined in, calling quiz shows the “newest translation of the American Dream.” The Question was an immediate ratings success, consistently occupying the top of the rankings and inspiring copycats, including NBC’s Twenty-One. There were knock-offs, but Twenty-One found an original angle, structuring the quiz as competition between two players with rules borrowed from blackjack.

When Stempel came on air, Twenty-One was a five-week-old newcomer struggling to break into the upper tier of a booming field of TV quiz shows. It was far from the only show offering outsiders a chance at fame and fortune—the Question made immigrant cobbler Gino Prato a household name in its first season. But that didn’t lessen the fact that Stempel could make it big, could win the American Dream by proving his wits and skill.

And prove them he did. In his first appearance, he won $9,000 in four minutes. Returning as the show’s champion for six weeks in a row, Stempel racked up just under $70,000 by December. Barry made sure to play up Stempel’s rags-to-riches story, introducing him as “our 29-year-old GI college student.” He was the outsider earning his way to the American dream by his merits alone, Twenty-One’s very own Gino Prato.

But after those six weeks, Stempel met his match. Opening the final show of November 1956, Barry introduced Charles Van Doren on air as Stempel’s next challenger. Van Doren didn’t require quite so much introduction to Twenty-One’s audience as Stempel had. Barry asked the challenger if he was “related to Mark Van Doren, up at Columbia University, the famous writer.” Charles’s own credentials were extensive enough—after earning his bachelor’s in the great books program at St. John’s College, he got a master’s in astrophysics and PhD in English at Columbia, where he then joined the English faculty—but Barry wanted to hear about his still more impressive family members. Van Doren answered in the affirmative—Mark was his father. Barry prodded him to say more: “The name Van Doren is a very well-known name. Are you related to any of the other well-known Van Dorens?” “Well,” Charles offered, “Dorothy Van Doren, the novelist and author of the recent The Country Wife is my mother, and Carl Van Doren, the biographer of Benjamin Franklin, was my uncle.” He could also have mentioned Carl’s ex-wife, Irita, longtime editor of The New York Herald-Tribune’s famed book review section.

The Van Dorens were the closest thing midcentury America still had to a WASP intellectual aristocracy. Many members of the family devoted their professional lives to spreading knowledge of great books, whether through their teaching (Mark, Carl, and Charles taught English at Columbia), writings in The Herald-Tribune or The Nation (where Mark, Dorothy, Carl, and Irita had been editors), or appearances on educational radio shows (Mark was a regular on “Invitation to Learning”). Mark in particular was known as a poet, literary critic, and advocate of great books education. They weren’t exactly the old WASP aristocracy—the family originated in rural Illinois—nor exactly the intellectual elite: New York’s intelligentsia had already diversified, in no small part thanks to Jewish thinkers and graduates of Stempel’s alma mater. The Van Dorens were holdouts of a genteel tradition that had been under siege for a half century, but still held cultural sway. They represented an ideal, built on the best of the West, even if they had to borrow their prestige from the aristocratic sources they emulated. The Van Dorens were America’s teachers.

However, Charles Van Doren was not going on Twenty-One to teach, but to prove his aptitude as a student. His father and uncle had both used radio to bring classic literature to mass audiences, reinforcing their position as intellectual aristocrats, as teachers. Charles expected that his appearance would similarly promote education, even though he came on the show in a different position. “Nothing is of more vital importance to our civilization than education,” he later said; he expected his Twenty-One appearance to have “a good effect on the national attitude to teachers, education, and the intellectual life.”

♦♦♦

Van Doren and Stempel tied their first game. They played a second game that episode, and tied again. Returning the following week, they tied twice more. For three weeks, Twenty-One dramatized a struggle between two visions of the American elite, one emerging and one receding. Stempel, the newly mobile beneficiary of American promise, battled a prince of the WASP intelligentsia. Van Doren’s high-bred charm was as apparent to audiences as Stempel’s awkwardness; he spoke gently and clearly, even when straining for an answer, dressed sharply, and carried himself like a gentleman. On December 5th, in the second game of their third week competing together, Van Doren beat Stempel on a question about newspapers. That victory was the first of a four-month streak during which Van Doren won $128,000—the highest total any quiz show had yet seen.

Van Doren was an immediate sensation. His fiancée Gerry had to help him respond to thousands of fan letters, including several hundred marriage proposals. Three months into his run, Charles made the cover of TIME magazine. The cover article compared the celebrity of “TV’s brightest new face” to Elvis’s, and described him as perfectly suited for TV fame: “Along with [Van Doren’s] charm, he combines the universal erudition of a Renaissance man with the nerve and cunning of a riverboat gambler and the showmanship of the born actor … It is difficult to imagine viewers tiring of the fascinating, suspense-taut spectacle of his highly trained mind at work.” Van Doren inspired the ultimate vote of confidence from NBC: moving Twenty-One from its Wednesday night time slot to Monday nights, opposite the final season of CBS’s ratings juggernaut I Love Lucy. Even up against the most popular show of the decade, Twenty-One climbed the charts, attaining a rating of 34.7, comfortably among the highest-rated programs on television.

Van Doren’s instant popularity reveals that, for all the optimism about the expanding American Dream that Stempel represented, and contrary to the much-publicized “anti-intellectualism” of McCarthy-era Americans, the public still looked up to well-cultivated, conventionally educated, erudite WASPs. TV critic Janet Kern found Van Doren “so likable that he has come to be a ‘friend’ whose weekly visits the whole family eagerly anticipates.” When a lawyer named Vivienne Nearing unseated him as the show’s champion on March 11, 1957, NBC offered Van Doren a three-year, $150,000 contract to stay on television. He became the Today Show’s cultural correspondent, reading poetry and reporting on events in the literary world.

Stempel may have left the air, but even after receiving his winnings and undergoing 10 months of therapy, he wasn’t done with Twenty-One. At the end of August 1958, he visited the office of New York Assistant District Attorney Joseph Stone and told him a story that no one had seen on television.

The whole thing had been fake, Stempel said. He had received the questions and answers beforehand from producer Dan Enright, told which levels of difficulty to select, and which to get right or wrong. But it wasn’t just the score that was rigged. Stempel’s mannerisms, clothes, banter before and after each game, and even his haircut were orchestrated by Enright and fellow producer Albert Freedman. Stempel wasn’t even from Brooklyn, but Queens. Enright and Freedman pushed Stempel out of the show in favor of Van Doren because ratings had, they told him, “plateaued,” and promised him a job in television if he agreed to lose. Stempel had come forward upon realizing that Enright and Freedman didn’t intend to fulfill their promise.

Nor was Stempel the only one who’d been rigged, as Stone quickly learned when other quiz show contestants began making similar confessions. He learned that every quiz show found ways to control results so that audiences could connect to the narratives of contestants. Pre-determined tics, pauses, and stutters could heighten a show’s dramatic tension and time it perfectly for commercial breaks. NBC had chosen to depict Stempel as a meritocratic underdog and made his rivalry with the ostensible aristocrat Van Doren the “plot” of their show.

But that rivalry, in Stempel’s mind, had never been fake. He insisted that he bore no ill will toward Van Doren, but there had been one incident that bothered him more than any on-screen defeat: Van Doren refused to shake Stempel’s hand after one game. It’s disputed whether Van Doren, too well-mannered to refuse a handshake, simply didn’t see the gesture, but the moment validated Stempel’s impression of his opponent as an elitist snob. Stempel was just as authentically an intelligent beneficiary of the new American dream—he was sure to point out to Stone his 170 IQ. Stempel had indeed attended City College because of the GI Bill, having served during the last month of the Second World War, although contrary to his low-class TV persona, he had married into money.

♦♦♦

But now Stempel was a different kind of underdog. He was now a slighted member of a minority group, appealing to government and public opinion against corporate and WASP powers that had offered him a bad deal. Stempel brought the struggle between two visions of the elite from the staged quiz-show drama into the broader world.

Stone conducted a nine month investigation into quiz show cheating, talking to contestants and producers from a variety of game shows, but Stempel made sure his was the central story. The day after he met with Stone, Stempel told his story to The New York Journal-American, which the next morning ran an article about an unnamed star of Twenty-One meeting with someone in the New York District Attorney’s office. A few days later, the paper ran another story on allegations of cheating on The $64,000 Challenge—a CBS spin-off of the Question. The DA’s office convened a grand jury, and although its proceedings were kept secret and no one was convicted or arrested, the Question, the Challenge, Twenty-One, and a number of other quiz shows were canceled during the fall of 1958. But even though the show and their roles on it were gone, Stempel’s rivalry with Van Doren would not disappear.

After the grand jury investigation and Twenty-One had both ended, Stempel received a visit from a federal investigator named Richard Goodwin. Goodwin was himself something of a meritocrat, having worked his way from lower-class Jewish suburbs of Boston to Harvard Law, landing a job with the House Subcommittee on Legislative Oversight. He’d never worked a case before, but after noticing an article in The New York Times about the quiz-show grand jury, he asked his superiors for permission to travel to New York to unseal the proceedings and investigate.

It’s easy to speculate as to why they let him go. The Subcommittee on Legislative Oversight had been recently established by the Committee on Interstate Commerce to keep tabs on the FCC as it distributed broadcast licenses—a hot commodity in television’s early days. In 1957, rumors of rampant bribery in the FCC led the subcommittee to ask NYU law professor Bernard Schwartz to conduct a probe of the agency. Schwartz’s investigation was perhaps more successful than Congress had hoped; the Commerce Committee cut it short after six months, during which time Schwartz revealed that the committee’s own chair secretly held a 25 percent stake in a television station. Schwartz’s discoveries led to the resignation of the FCC director and other officials. By the fall of 1958, the Subcommittee may have been looking for ways to scratch the public itch for exposing corruption in television without further implicating members of Congress.

Whatever the case, the young Goodwin certainly didn’t see his investigation as mere misdirection from his bosses’ corruption. In his mind, quiz show cheating amounted to an offense against the public, and as a civil servant, he was the public’s champion, duty-bound to deliver truth and justice even if it meant stretching procedural bounds—an attitude that would later serve him well in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. Requesting the grand jury’s records from the presiding New York judge was something of a power trip: “With a single sentence, I had overturned the intentions of the New York judicial system. True, the power was borrowed, derived from my employers. But since its exercise was mine, it also belonged to me.” Even Quiz Show finds Goodwin a bit too powerful—in the movie, he fails to retrieve the grand jury report and has to conduct some boots-on-the-ground sleuthing.

Goodwin’s cavalier conduct rubbed Stone the wrong way. From Stone’s perspective, the “aggressive” Goodwin “assumed what amounted to carte blanche authority,” and “terrorized producers, advertising men, former contestants, and others by brandishing blank subpoenas.” Nothing stood in the way of this crusading bureaucrat. The New York grand jury had already ruled, the quiz shows had shut down relatively quietly, and nobody had been arrested, but Goodwin was building a cause célèbre to be adjudicated as much in the public and the press as in government.

The young lawyer’s bravado worked, as his investigation led to a series of high-profile hearings in the fall of 1959. One week short of the three-year anniversary of Stempel’s first appearance on Twenty-One, the ex-contestant stepped back into the public spotlight. Committee chairman Oren Harris opened the hearings with a remarkably broad justification: not to investigate wrongdoing, but “to assist the committee in considering legislation pertaining to Federal regulatory agencies within its jurisdiction.” Stempel was the first witness. To prove that he’d received answers in advance, he revealed that the day before he was supposed to lose he’d given the answers to a salesman friend, Richard Janofsky, so Janofsky could prank his wife when they watched the show together.

Every witness pointed the finger at Enright and Freedman, though Goodman had hoped to implicate executives at NBC or Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Twenty-One’s sponsor). The subcommittee learned that Pharmaceuticals, Inc. had approved Enright sending Stempel, Van Doren, and Nearing several-thousand-dollar checks as advances on their prize winnings when it was still possible (under the rules of the game) that they’d lose all their winnings—almost as if the advertiser who cut the checks knew ahead of time they wouldn’t lose. When the subcommittee grilled him on the subject, Edward Kletter, the company’s VP and advertising director, equivocated and sidestepped. Eventually, pressed into a corner, Kletter told the subcommittee that he had approved the advance not out of foreknowledge, but out of the kindness of his heart: “It is my firm belief that if Mr. Van Doren had lost it all, he would have returned the money. … You just don’t turn somebody down if he has a good reason for asking for help.” Van Doren had asked Enright for the advance because he had Christmas shopping to do. There wasn’t enough evidence to prove a wider conspiracy.

The subcommittee was more interested in Twenty-One’s contestants. New York Representative Steven Derounian wanted Van Doren’s head. A Bulgarian-born Armenian-American, Derounian may have shared some of Stempel’s resentment of advantages enjoyed by apparent WASPs like Van Doren. His questions for Stempel were pretense to pontificate on Van Doren: “Mr. Van Doren has built himself up as an intellectual giant in the eyes of the American people and is making a lot of money today on [Today] telling sweet stories of art, poetry, and compassion for humankind. Is it reasonable to assume, based on your information, that Mr. Van Doren also got the Enright preparation?” Stempel replied that he couldn’t make any accusations—he simply wasn’t a vindictive person. But Derounian insisted: “You told your friend, Mr. Janofsky: ‘You, too, can be smart if you know the answers in advance.’ Does that apply to Mr. Van Doren, in your opinion?” It’s easy to read in these questions an insinuation that all Van Doren’s virtues were the results of prejudice, advantages given “in advance,” whether by producers or by birth.

Van Doren’s confrontation with the newly upwardly mobile had moved from TV to the halls of Congress. His name now caught up in scandal, Van Doren issued a statement on the third day of the hearings (prepared for him by NBC) denying having received assistance on Twenty-One. The committee replied by subpoenaing him. When he arrived for the second round of hearings early in November, Van Doren took the oath, sat down, and addressed the chairman:

“I would give almost anything I have to reverse the course of my life in the last three years. I cannot take back one word or action; the past does not change for anyone. But at least I can learn from the past. … I have a long way to go. I have deceived my friends, and I had millions of them.”

Van Doren confessed to everything. Enright and Freedman had fed him answers, although he begged them despite his popularity to take him off the show, which they did upon finding Nearing. When he finished speaking, most of the committee members responded politely, willing to give due deference to a humbled man admitting his wrongdoing. But Derounian pounced. “Mr. Van Doren, I am happy that you made the statement, but I cannot agree with most of my colleagues who have commended you for telling the truth because I don’t think an adult of your intelligence ought to be commended for telling the truth.” He told Van Doren, “what you did, you did for money.”

Derounian’s harshness anticipated the public reaction to Van Doren’s confession. The movie expresses it well. As they leave the congressional chambers, the Van Dorens, fresh off Derounian’s ridicule but hoping for a graceful exit from the public eye, step into a swarm of reporters who tell them both NBC and Columbia have fired Charles. This avalanche of bad news is only a slight dramatization—Charles did indeed learn from reporters that he was fired both from the Today Show and Columbia, but not until he arrived home. The project of tearing down the privileged would be total. The justice delivered by a grand jury behind closed doors wasn’t enough; holders of privilege were now subject to public destruction of reputations and removal from jobs. As Freedman told the subcommittee, “over the past year [since Twenty-One ended], as a result of all that has happened, people have been hurt—contestants, people working in our organization, have been very hurt. Reputations have been hurt.” But reputations didn’t matter much anymore. The noble lie that sustained the WASPs and made the Van Dorens celebrities—that their position as America’s teachers came from good breeding, manners, and education, rather than mere privilege—shattered just in time for the ’60s to begin, and it already looked as though the new regime was going to be merciless.

♦♦♦

Herbert Stempel’s struggle with Charles Van Doren is far more complicated than it seemed to Twenty-One’s viewers in the fall of 1956. Stempel wasn’t the poor Brooklyn boy surviving on his wits and merits alone, and his federal champions weren’t pursuing truth and justice but self-vindication. But neither was Van Doren the stuffy WASP that Stempel disliked and audiences adored. And crucially, contrary to appearances, neither was Van Doren truly the person in power. As Goodwin recognized, the congressional hearings absolved (or ignored) corporate powers-that-be and focused on attacking the apparently privileged WASP.

Stempel’s grievance was doubtless legitimate, regardless of whether Van Doren missed a handshake or whether Enright cheated him out of a job. But that grievance’s effectiveness ultimately had more to do with congressional desire for good publicity and Van Doren’s own mistakes than its own justice. Van Doren did his part to undermine public acceptance of WASP privilege, not only by cheating, but by going on Twenty-One in the first place. He hoped his participation would promote elite education and erudition as attainable for everyone—but if it’s for everyone, then people like Mark and Carl Van Doren had no unique claim to it, or to the position of America’s teachers. Twenty-One subjected Charles’s aristocratic virtues to meritocratic standards, and he didn’t live up.

Popular memory considers the ’60s a moment of great disruption, including of the WASP elite, but that disruption began earlier, at the height of WASP popular cultural influence. Today’s elite stands at a similar apex of influence, cooperating with mass media not to spread knowledge of literature, history, and philosophy, but of diversity, inclusivity, and intersectionality. But this cooperation can be risky. There may be no better way to create and spread discontent with reigning elite values than broadcasting them nationally. Mass media might end up making promises that elites can’t keep. And no matter how entrenched and widely beloved a cultural elite may seem, it can only take a few years, a slighted outsider, or a broken public promise to change everything.

Philip Jeffery is assistant editor at the Washington Free Beacon. His Twitter handle is @philipljeffery.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com