This story is part of a group of stories called

Uncovering and explaining how our digital world is changing — and changing us.

A year ago, when Facebook launched its own video chat device, it seemed like a clueless move by an out-of-touch tech giant: Under fire for abusing its users’ privacy, Facebook was still stumbling forward with a video camera that would surveil its users in their homes.

Who would want that?

Plenty of people, Facebook seems to be insisting: Rather than walk away from its Portal devices, Facebook is pushing out more of them, including one that’s supposed to let your friends watch you watching Facebook videos on your TV.

But wait! That’s not all. Facebook has also confirmed that when you bark a command at a Portal, Facebook contractors may end up listening to what you say.

Facebook’s rollout of the new Portal devices is both puzzling and par for the course in 2019, when big tech companies are condemned for the way they treat their users and their personal information, yet remain committed to business plans that depend on users’ data.

It also underscores why it’s legitimately confusing to assess the pervasiveness of the “techlash” that journalists and others have been talking about for the past three years.

On the one hand, it seems as if tech companies are in the midst of a long-overdue reckoning, forced upon them by some combination of the press, regulators, and actual consumers. On the other hand, in their day-to-day activities, many consumers seem okay with giant tech companies — or, at least, they aren’t upset with them to the point where they’ve stopped using them in meaningful numbers.

This dissonance is anywhere you look. Like this site, for instance: Today my colleague Emily Stewart reports on a poll that suggests that two-thirds of Americans are in favor of breaking up big tech companies like Facebook, Amazon, and Google. But there’s no evidence that two-thirds of Americans are signaling their discontent in any way that’s more meaningful than responding to a poll — or complaining about the platforms on the platforms themselves.

Sure, things can change. It’s possible, for instance, that while tech has yet to command much attention in settings like the Democratic presidential debates, it could play a significant role in the 2020 elections. And that the winners of those races will be emboldened to rein in the big tech platforms.

There is also a very good possibility that any tech regulation that passes — if any regulation passes at all — will end up reinforcing the dominance of the current tech giants, which is one of the criticisms you often hear about European privacy regulations that recently went into effect.

In any case, Facebook — a company that frequently has to tell people that it doesn’t secretly listen to its users’ phone conversations in order to serve them ads so personalized that some people find them creepy — seems to be betting that there are many people who aren’t skeeved out by a Facebook-branded video chat system. It also thinks users will be comfortable placing a Facebook-branded camera by their TV, one that would watch them while they watch television.

You can imagine different rationales Facebook execs considered while developing this product rollout. Many of them are plausible.

For instance:

- Microsoft used to sell something called a Kinect, a camera that people were supposed to place by their TV that would watch them while they played on their Xbox. It never got any serious privacy blowback.

- When Amazon sold its first Alexa-enabled home speakers in 2014, it sure seemed like an unlikely success because who would buy a device that let Jeff Bezos listen to you in your house? But Amazon says consumers have bought more than 100 million Alexa devices.

- If you already have a smart TV, the odds are very good that it’s watching what you watch and reporting that back to people who want to show you ads.

So you might imagine Facebook executives telling themselves, “Consumers might say they care about privacy. They don’t behave that way. And if they want to buy devices that listen to them in their home or watch what they watch on TV, why shouldn’t we be the ones to sell them?”

Then again, you might think Facebook would pause its new Portal push in light of public outcry over recent revelations that every tech giant that uses some kind of speech detection feature — like Amazon, Google, and Apple — has been paying human beings to listen in on users’ conversations.

Instead, it turns out that Facebook — which, again, has to constantly tell reporters and regular humans that it isn’t surreptitiously listening to their phone conversations — was indeed recording and storing the commands spoken to their Portal device.

It also turns out, Facebook did pause its Portal audio collection and review program this summer. “The consumer reaction the last several months to these practices, not just at Facebook but other companies, gave us insight into the fact that this was something people weren’t entirely comfortable with or weren’t sure about,” Facebook exec Andrew Bosworth told Bloomberg.

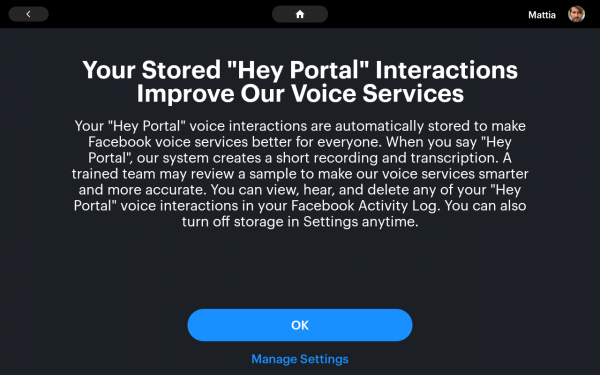

But now, Bosworth says, Facebook thinks consumers will be okay after all with Portal listening to them talk. Facebook — the company that just agreed to a $5 billion fine as punishment for abusing its users’ privacy and is now adding layers of compliance rules and lawyers to make sure it doesn’t happen again — has restarted the program. And while it lets users remove the stored voice interactions so they won’t be reviewed by Facebook contractors, it makes users opt out of the program; the default setting leaves it on.

Maybe Facebook is deeply mistaken about the way its users think about privacy and about Facebook’s ability and desire to protect that privacy. Maybe it’s correct and many of us are overestimating regular humans’ antipathy for the technology baked into their daily lives. Or maybe the truth is somewhere in the middle, unevenly distributed, and we are figuring it out as we go.

Sourse: vox.com