The disturbing hypothesis for the sudden uptick in chronic kidney disease

Our kidneys might be vulnerable to the more frequent extreme heat brought on by global warming.

By

Julia Belluz@juliaoftoronto

Updated

Sep 4, 2019, 6:18am EDT

Share this story

-

Share this on Facebook

-

Share this on Twitter

-

Share

All sharing options

Share

All sharing options for:

The disturbing hypothesis for the sudden uptick in chronic kidney disease

-

Twitter

-

Facebook

-

Reddit

-

Pocket

-

Flipboard

-

Email

This story is part of a group of stories called

Finding the best ways to do good. Made possible by The Rockefeller Foundation.

In its early stages, chronic kidney disease can lurk silently in the body, causing no symptoms at all. Eventually, as these vital organs fail, the hands and feet start to puff up, and sufferers feel nauseated, achy, and itchy. When the disease reaches its last stage, the kidneys fail and you can die.

In the 1990s, health officials noticed that chronic kidney disease was on the rise in Central America. An epidemic seemed to be raging among farmworkers who toiled in sugarcane fields on the Pacific Coast in El Salvador and Costa Rica — one of the hottest areas in the region. To date, more than 20,000 people have died in the epidemic, and thousands of others have had to go on kidney dialysis to survive.

Researchers are now coming together around a hypothesis about what’s driving a little-appreciated epidemic, known as “Mesoamerican nephropathy.”

One main suspect: global warming. It has become a leading hypothesis to explain not just Mesoamerican nephropathy but a similar uptick in chronic kidney disease in India and Southeast Asia. The victims could be called “climate canaries.”

Roberto Lucchini, an environmental and public health professor at Mount Sinai who’s been studying the phenomenon, calls this the first epidemic that’s directly attributable to climate change. “It was not recognized before the rise in temperatures,” he said, “and the epidemic of these cases is currently observed in the countries that are more affected by [global warming] in the last decades,” from Central America to India and Southeast Asia.

A new editorial, in the New England Journal of Medicine, augurs a “new era of climate-health crises,” during which “known diseases are being exacerbated and new diseases are arising.” Chronic kidney disease “is likely to be just one of many heat-sensitive illnesses that will be unmasked and accelerated by climate change.”

The epidemic might also be happening closer to home. Recent studies focused on California and Florida suggest the disease may already be afflicting people who work outdoors in the southern US too.

The basic idea: When people are exposed to long stretches of extreme heat, they sweat more. If they don’t rehydrate, or don’t have access to clean drinking water, the kidneys, which are supposed to filter waste and regulate fluid in the body, get stressed. Over time, that stress can lead to kidney stones and chronic damage.

“The hypothesis is that weeks and months of sustained, acute kidney injury [due to heat exposure] could potentially destroy the kidneys’ ability to function,” said Linda McCauley, dean of the nursing school at Emory University, who has been studying kidney failure among farmworkers in Florida.

Another possibility is that the workers have been exposed to environmental toxins, such as pesticides or heavy metals. Or maybe it’s an infectious disease, like leptospirosis.

But according to McCauley, it’s not that far-fetched to think that as temperatures continue to rise and record-setting hot days multiply, the risk of kidney problems — especially among vulnerable populations, like outdoor workers and the elderly — is only going to grow.

Why researchers think climate change is stressing outdoor workers’ kidneys

The kidneys, two bean-shaped organs that sit below the ribcage, act as filtration systems for our bodies. They clear out waste and excess fluid by creating urine, sending it to our bladders, so that our blood constantly contains the optimal balance of salts, mineral, and water. (Kidneys also do a bunch of other cool stuff, which you can read about here.)

But a number of things can stress the kidneys’ ability to function. The most well-known contributors to chronic kidney disease are other chronic illnesses, like diabetes and high blood pressure. Around the world, as diabetes and high blood pressure have become more common, so has chronic kidney disease.

When researchers discovered that farmworkers in Central America who didn’t have these underlying conditions had developed chronic kidney disease, they became curious.

“It was first noticed in El Salvador, where along the coast, people were getting kidney disease and being referred to the main hospital with kidney failure,” said Richard Johnson, a kidney disease expert and professor of medicine at the University of Colorado. “The wards were filling up with people with chronic kidney disease or end-stage kidney failure, and these people didn’t have the typical causes of kidney failure,” like high blood pressure or diabetes. They were often in their 30s and 40s, and seemingly otherwise healthy.

An initial investigation showed many of the afflicted had been working outside, particularly in sugarcane fields, where temperatures can surpass 82 degrees Fahrenheit by midmorning. The locations of the kidney disease epidemic on the Pacific Coast overlapped with areas in the region that have seen some of the most dramatic rises in average daily temperatures since the 1940s.

There was (and still is) speculation about whether other factors — chemicals from pesticides, for example — were driving the increase. But when health officials started to spot similar trends in Sri Lanka and India — other areas that have become significantly hotter on average — they began to explore climate change as a contributing factor.

“Our [research] group, and others, recognize that a very common denominator across these communities was that they were working under extremely hot conditions, where hydration was not optimal,” said Johnson, who co-authored a 2019 New England Journal of Medicine review article on the potential drivers of the epidemic. “And some of the people were suffering from dehydration.”

Johnson and his colleagues collected urine samples from the sugarcane workers. “We found evidence of dehydration, and that many of them would form crystals of uric acid in their urine that could damage the kidney.”

A group of climate researchers, also at the University of Colorado Boulder, investigated, and discovered that these kidney disease epidemics were more likely to occur in places with rapidly rising temperatures, longer and more frequent heat waves, and less rainfall.

In one epidemic site on the Pacific Coast, Costa Rica’s Guanacaste province, for example, the prevalence of Mesoamerican nephropathy is believed to have increased almost tenfold in men and fourfold in women since the 1970s.

“This kind of evidence makes it likely climate change is playing a role in this epidemic,” said Johnson. “Whether it’s the dominant role or a risk factor we’re not certain, but there does seem to be a relationship between heat stress, dehydration in the kidney, and what we are seeing is an increase in heat waves in these regions that could account for why the epidemic is manifesting.”

Kidney problems are surfacing in the US

The Central America data prompted researchers in the US to examine whether extreme heat is affecting kidney function in outdoor workers here.

For the “Girasoles (Sunflower) Study,” published in May 2018 in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, McCauley of Emory and her co-authors looked at the hydration status and kidney function of 192 Florida agricultural workers, most of whom picked field crops and hailed from Mexico.

They found that more than half (52 percent) showed up at work already dehydrated — perhaps because of a hot commute to work or not drinking enough water when they woke up. By the end of a shift, that number rose to 81 percent. And a third of the workers had endured at least one episode of acute kidney injury — a sudden decrease in kidney function that happens over a few hours or a few days — on a workday.

Meanwhile, the odds of acute kidney injury increased by 47 percent for every 5-degree rise in the heat index in Florida. So people in the study were more likely to experience acute kidney injuries on hotter days.

It didn’t help, McCauley said, that workers sometimes delay going to the bathroom because it means pausing work and losing wages. So social circumstances, and the lack of worker safety protection, made workers more vulnerable to weather extremes.

“Our findings suggest that immigrant agricultural workers in Florida agriculture have a high burden of dehydration and experience adverse changes in kidney function during their workdays,” the authors concluded. “Increased global climate temperatures will increase the vulnerability of agricultural workers to [heat-related illness] in the future and this presents a critical public health challenge.”

Researchers at the University of California Davis who have been studying heat trends identified similar risks in California. For a 2016 study, part of the California Heat Illness Prevention project, they looked at 295 agricultural workers and found 12 percent had experienced acute kidney injury over the course of one day at work.

Other vulnerable populations may also be at risk. In a 2014 study of hospital admissions among adults ages 65 and older during extreme heat events — defined as two or more consecutive days of uncharacteristically hot temperatures — researchers found the risk of kidney failure was higher on heat wave days compared to non–heat wave days.

“We know heatstroke can kill people,” McCauley said. “But this possibility that we’re seeing a wave of kidney disease associated with climate change is quite a new thing.”

The “kidney stone belt” is expected to move north

Dehydration from heat also puts the kidneys at an increased risk of forming painful stones — and there’s another climate-related kidney hypothesis floating around: that the incidence of kidney stones may soon increase in parallel with rising global temperatures.

Doctors have long known that a person’s risk of kidney stones goes up when ambient temperatures rise. That’s because when we sweat, we produce less urine. And when people don’t pee often enough on a regular basis, the waste products that are supposed to come out through the urine settle and clump up in the kidneys. (Stones are also a risk factor for chronic kidney disease.)

So the more a person sweats, and forgets to rehydrate, the more likely they are to form kidney stones.

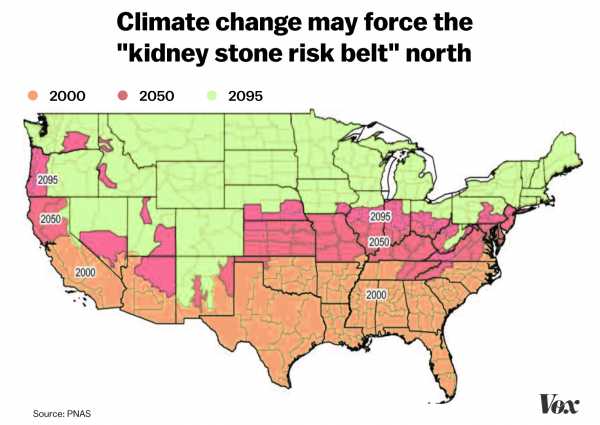

Kidney stones are common in the southeastern part of the country, an area that’s known as the “kidney stone belt.” (The prevalence there is 50 percent higher than in the Northwest.) Part of this is driven by the epidemic of cardiovascular disease and metabolic problems — such as diabetes and obesity — in the South.

But heat, as we’ve discussed, is believed to be a contributing factor. And as the temperatures rise across the country, some researchers expect the problem will worsen in the South and spread north through the US.

In a 2008 paper published in PNAS, researchers at the University of Texas used climate prediction models produced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and showed that as temperatures in the US increase, the US kidney stone belt is going to expand north. The greatest increases in stones will be in some of the areas most affected by warming — California, Texas, Florida, the eastern United States, and the stretch of land from Kansas to Kentucky.

But altogether, climate-related kidney stones cases in the US will increase 30 percent by 2050, the researchers predicted, from 1.6 million cases to 2.2 million. By that time, 70 percent of Americans are projected to live in high-risk kidney stone areas, compared to 40 percent in 2000.

Kidney stone disease is already on the rise in the US, even among children. According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the kidney stone prevalence was 5.2 percent in the mid-1970s. By 2010, it had increased to 8.8 percent (11 percent among men and 7 percent among women). Again, that’s thought to be because other chronic diseases have become so prevalent.

Hot days are already a risk factor for stones. In one 2014 study, a group of researchers in Philadelphia showed that hot days — when the average daily temperatures rose to 30 degrees Celsius — were associated with a relative risk increase for stones compared to cooler days (below 10 degrees Celsius) in five US cities. But climate change might soon make the problem worse.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Sourse: vox.com