The Dartmouth versus Princeton football game of November 1951 was, by all accounts, brutal. A Princeton player broke his nose. A Dartmouth player broke his leg.

But in the aftermath, each side blamed the other for instigating the violence. With so much debate about “who started it,” two psychologists, Albert Hastorf of Dartmouth and Hadley Cantril of Princeton, united to answer this question: Why did each school have such a different understanding of what had happened?

Hastorf and Cantril decided to run a very simple test. They asked students at each university to watch video highlights from the game. During the replay, the students were instructed to pretend to be the referees. In the results, the rival students greatly disagreed over which team was more at fault.

The psychologists concluded it was like the two sets of fans were watching a different game. ”It seems clear that the ‘game’ actually was many different games and that each version of the events that transpired was just as ‘real’ to a particular person as other versions were to other people,” they wrote in their influential 1954 paper. Princeton fans wanted Princeton to look good. Same for Dartmouth.

This idea that we see what we want to see is called motivated perception. It’s similar to another concept — motivated reasoning, where we come to conclusions we’re predisposed to believe in.

But the Princeton-Dartmouth study left many unanswered questions, since the researchers didn’t know if the fans truly “saw” different versions of the game or if they just said they did. That is: Were they just lying?

It’s a key question, one that’s captured the imagination of a new generation of psychology researchers today.

Recently, Yuan Chang Leong, a postdoctoral researcher at UC Berkeley, and co-authors published a neuroscience experiment in Nature Human Behavior that lends evidence to the idea that people really do “see” things differently. “Knowing that other people could truly be seeing things differently from us is a way of being able to better understand them and empathize with how they feel,” Leong says.

It also helps us understand ourselves. Recognizing that our perceptions of the world don’t necessarily reflect the pristine truth of the world is humbling. There’s an important, overarching thing to know about how our brains perceive the world: They’re constantly guessing.

How your brain perceives the world

We know it’s possible for two people to look at the same image and see two completely different things. Just think of “the dress.” The image that went viral in 2015 was incredibly polarizing: Some looked at it and saw it was blue and black, and others saw white and gold. How is this possible?

The photo projects light into our eyes, but there’s enough information in that light for the image to be interpreted in two ways. Our brains decide to pick one interpretation over the other (and then get pretty stubborn about it).

This is the truth about how our brains work: Light enters our eyes, sounds enter our ears, smells enter our nose, but what we end up perceiving may not be a perfectly accurate representation of the world.

“Our eyes are very far removed from the parts of our brain that are seeing,” Jay Van Bavel, a neuroscientist at NYU, explains. “So the information goes through neurons to the back of our brain [where the visual cortex is located], and then we slowly piece the information back together as it hits the back of our brain.”

But as that information gets put back together, it can be influenced by a variety of things.

It’s influenced by what we pay attention to (the different interpretations of the dress may have to do with whether you see evidence that the dress is covered by a shadow or not). It can also be influenced by context.

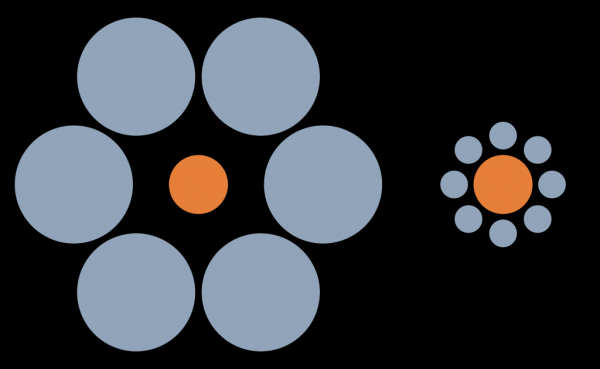

For instance, in the classic Ebbinghaus illusion seen below, the orange circles are the same size, but the left one looks a lot smaller. The exact reason why is still debated. But the overall idea is this: The extra information in the image, the large and small blue circles, nudges our brains to make a wrong guess.

Perception can be altered by expectations and stereotypes too: Many people perceive black men to be bigger (and therefore more threatening) than they actually are. Cops can confuse people taking out wallets from their pockets for guns, with tragic consequences.

Another influence: motivation. We tend to see what we want to see, especially when it’s possible — like the dress — to come to different conclusions from the same information.

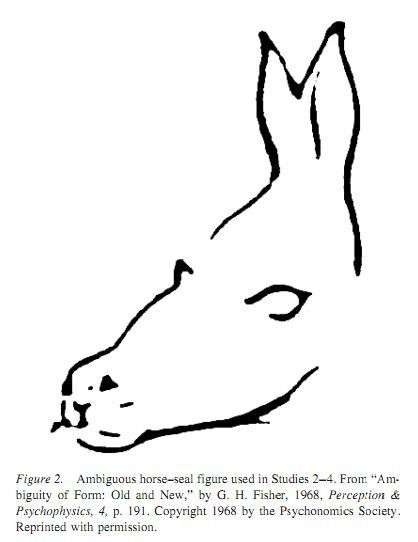

In the past, researchers have found that even slight rewards can change the way people perceive objects. Take this classic image used in psychological studies. What do you see?

It’s either a horse or a seal, and in 2006, psychologists Emily Balcetis and David Dunning showed they could motivate study participants to see one or the other. In one of their experiments, the participants were playing a game where they had to keep track of animals they saw onscreen. If they saw farm animals, they’d get points. If they saw sea creatures, they’d lose points. In the end, a high score meant getting a candy treat (desirable!) and a low score meant they’d eat canned beans (kind of weird!).

The very last image the participants saw was the one above. If seeing the horse meant they’d win and get the candy, they’d see the horse. The same was true in a version of the experiment when the sea creature was worth more points.

That’s cool. But this experiment, and the variations of it in the study, didn’t completely answer the big question: Were the participants simply reporting they saw the desirable image, or were they seeing it?

Brain scans reveal we truly might see things differently

Leong’s group played a similar type of game as Balcetis and Dunning but employed an MRI brain scan to better understand how people process these ambiguous images in the brain.

Around 60 participants were brought into the lab — 30 of whom underwent the MRI. (It’s a small sample size, but MRI studies tend to be extremely expensive.)

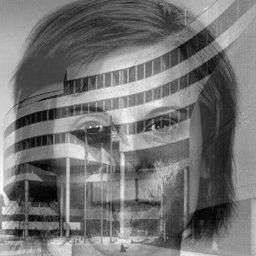

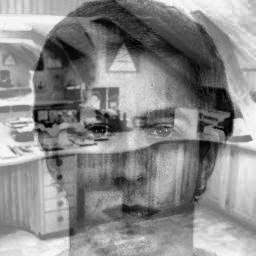

As in the Dunning and Balcetis study, they played a game in which they saw images that were blended together. Each image was partly of a face and partly of a scene. Here are some examples. They are each 50 percent face and 50 percent scene.

In some pictures, the face dominated the image. In others, the scene did. The participants were asked to guess what they saw more of in each photo: face or scene? If they guessed correctly, they’d win some cash.

Simple, right?

Not quite, because Leong introduced a complication: “On top of that we also biased them to want to see one category over another,” Leong says. After each trial in the game, participants were told that, regardless of how they performed, if the next photo contained more scene, they’d win more money. Other times, they were told they’d lose some money if the next picture contained more face. And so on.

But even with this complication, it remained the case that if the participants guessed correctly, they’d still win the most amount of money overall.

To simplify, the participants were motivated to want to see more of one image or the other, but succumbing to that motivation wasn’t in their best interest.

Yet the motivation to see a face or a scene was largely irresistible, even when it hurt the participant’s winnings. Participants were more likely to see what the experimenters motivated them to see. “It’s [one] reason why our data suggests it’s unlikely to just be a response bias,” Leong says. “It’s almost as if you’re hurting yourself by being biased.”

Okay, cool. That basically replicates the classic findings in this literature. But it still didn’t answer the big question.

To do that, the researchers peered into half of their participants’ brains with fMRI while they were playing the game. In those brains, there’s actually a different pattern of brain activity when we’re looking at faces compared to when we’re looking at scenes. The researchers actually recorded, in each participant, how their brains responded to looking at a face and how they responded to looking at a scene.

When the participants were shown the blended photographs, the researchers could then ask whether their brains were processing this information like a face or like a scene.

The study found evidence that when motivated to see a face, the participants’ face area in their brain was more active and vice versa. That’s evidence — though not perfect evidence — that their subjective experience is altered by motivation. It’s still hard to conclude this brain activity reflected their subjective experience.

“We have no access to people’s subjective experience,” Leong says. “What our paper contributes is to actually decode the neural representation of the images in the brain, and I think that adds evidence to show it’s not just they’re actually representing [the images] differently in the brain.”

Overall, Leong says his team found evidence that it’s not just our perception that’s biased; at times, we’re also biased to just say what we want to see.

Both biases “are usually both there, but not always,” Leong says. “There are a few participants who exhibit a response bias but not perceptual bias and vice versa.”

So what can we do about it?

Balcetis, the NYU psychologist who authored the 2006 paper with Dunning and pioneered much of the recent research in motivated perception, says of all our senses, we tend to trust our eyes the most. (She was not involved in this new study.)

“We have this naive realism that the way we see the world is the way that it really is,” she says. Naive realism is a blind spot in all of us. It’s the feeling that our perception of the world reflects the truth. It’s the reason that when confronted with polarizing illusions like the dress, we feel stubborn and perplexed: How could anyone see it another way?

That feeling can also lead to conflict.

“Biases in how we perceive the world could also enhance polarization,” Tali Sharot, a cognitive neuroscientist at University College London, writes in a commentary in Nature Human Behavior that accompanied Leong’s paper. “This is because the same exact event, perceived differently by two individuals, may cause both to become more confident in their conflicting opinions.”

That’s how fights between sports fans start. It’s how opposing political parties look out into the world and see different sources of threat. “All illusions [and you can think of racism as a sort of like a social illusion] are not operating through the exact same process,” Van Bavel says. Again, there are many motivations, expectations, and biases that can lead us to perceive the world in one way, or another.

It’s not that “our brains are broken” and we can’t trust anything we see. “For the most part, our brains are really smart,” Bacetis assures me. Our brains are predictive, trying to be efficient. For the most part, this system serves us well.

What’s so hard about dealing with our biases is how silently they operate in our mind. We’re not always aware of our motivations and our expectations. And, as Yeong’s experiment demonstrates, we even fall for them when they’re not in our own best interest.

But he hopes that the mere awareness of it can inspire people to think more about how they might be wrong. “At least knowing you are biased gives you the space, the opportunity, the awareness that you could do something about it,” he says. “Whether it would work or not, I’m not sure, but at least you could do something.”

In her ongoing work, Balcetis says she tries to get people to literally change the way they see things. For example, in an ongoing study, she’s showing participants a video of an altercation between a police officer and a citizen. She’s wondering, if you merely tell people “make sure that you pay equal attention to both the police officer and the citizen,” if their eye movement changes, and whether that leads them to different conclusions as to who is at fault.

For what it’s worth, even Yeong says he answers the questions in his experiment in a biased way. “I know how the experiment is set up, and I manage to find bias in my own data,” he says. “I make peace, at least personally, that it [perception] is a guess. I think it’s humbling; it reminds me that I’m not always right. Just because I see things one way doesn’t mean that it’s the only way to see them.”

Sourse: vox.com