A familiar pattern plays out after every mass shooting in the US.

First, advocates of gun control point out, accurately, that taking guns off the streets and limiting who can buy them will save lives. Then opponents of gun control argue that there are no regulations that can stop a determined shooter and that what we really need is to address mental health.

“This is also a mental illness problem,” President Trump said, following the script, after shootings in Dayton and El Paso. “These are people that are very, very seriously mentally ill.” “Mental health is a large contributor to any type of violence or shooting violence,” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott agreed.

Then liberal gun control advocates insist they too want better mental health care and that Republican gun control opponents are hypocrites because they oppose expanding access to health insurance that would help people get it.

But the convenient cries of “mental health” after mass shootings are worse than hypocritical. They’re factually wrong and stigmatizing to millions of completely nonviolent Americans living with severe mental illness.

Abbott is wrong: the share of America’s violence problem (excluding suicide) that is explainable by diseases like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder is tiny. If you were to suddenly cure schizophrenia, bipolar, and depression overnight, violent crime in the US would fall by only 4 percent, according to an estimate from Duke University professor Jeffrey Swanson, a sociologist and psychiatric epidemiologist who studies the relationship between violence and mental illness.

“People with mental illness are people, and the vast majority aren’t any more of a risk than anyone else,” Swanson says.

That doesn’t mean, he says, that we can’t do more to identify people at risk of committing gun violence and prevent them from getting guns — particularly if they are a danger to themselves or others. But portraying mass shootings as a mental health problem misrepresents the evidence.

Mental illness isn’t a major cause of gun murder or mass shootings

The data on mental illness and violence is somewhat tricky to wrap your head around at first. People with severe mental illnesses — particularly schizophrenia and bipolar disorder — do have an increased risk of violence compared to the general population. But the absolute risk they pose is not high (being male or having a substance abuse issue are both bigger risk factors), and the vast majority of people with severe mental illness aren’t violent.

Mentally ill people are far, far likelier to be the victims of violence (including violence committed by police) than the perpetrators. And because a distinct minority of the population has schizophrenia or bipolar, mental illness doesn’t contribute much at all to the overall violent crime problem.

A study conducted from 1980 to 1985 illustrates these complicated dynamics well. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study, sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health, conducted an ongoing survey of about 10,000 people in five different urban areas (Baltimore, St. Louis, Raleigh-Durham, New Haven, and Los Angeles), asking, among other things, diagnostic questions to see if respondents met criteria for mental illnesses, and if respondents had hit, punched, pushed, shoved, or otherwise violently attacked someone.

Before the ECA study, attempts to study mental health and violence typically started either in psychiatric hospitals or in the criminal justice system. Those methods have obvious problems: Scouring hospital wards only catches people who’ve been diagnosed and chosen or forced to get help, and scouring prisons doesn’t give you a representative sample of the mentally ill either. By using a general household survey, the ECA study avoided those biases.

The study did find that people meeting diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar were more likely to report violent behavior. But, as Swanson found analyzing the study data, the attributable risk rate — that is, the share of overall violence explained by serious mental illness — was between 3 percent and 5.3 percent, for a midpoint estimate of about 4 percent. That’s where the idea that if you wiped out serious mental illness overnight, violence would fall 4 percent comes from.

The contribution isn’t just small, however; a large part of it is due to factors that often come with mental illness, rather than mental illness itself. A 2002 paper by Swanson and seven co-authors, looking at 802 people in treatment for severe mental illness (which, as discussed earlier, biases the sample a bit), examined how the relationship between mental health and violence varies by social factors like substance abuse, childhood maltreatment, and living in an adverse or violent social environment (like being homeless or living in a very high-crime area of an inner city).

What they found was that mentally ill people who didn’t have substance abuse issues, who weren’t maltreated as children, and who didn’t live in adverse environments have a lower risk of violence than the general population.

“If you add any one of those three, it doubles,” Swanson says. “If you add any two, it doubles again. If you have all three, your risk triples.” Subsequent research using Swedish data finds that while non-substance-abusing mentally ill people have only a slightly higher risk of violence, substance abuse hugely increases that.

Given that mentally ill people are substantially more likely to have substance use issues, to live in adverse environments like homelessness, and to have been maltreated as children, it stands to reason that their rates of violence should be higher. That exaggerates the effect that mental illness itself has on violence.

Nor does this picture change when you look at just mass shootings and mass murders, not all violence or all homicides. Michael Stone, a psychiatrist at Columbia who maintains a database of mass shooters, wrote in a 2015 article that only 52 out of the 235 killers in the database, or about 22 percent, were mentally ill. “The mentally ill should not bear the burden of being regarded as the ‘chief’ perpetrators of mass murder,” Stone concludes.

Northeastern University criminologist James Alan Fox, a frequent writer on mass murder and mass shootings, and fellow researcher Emma Fridel analyzed a Stanford Geospatial Center database compiling shooters who killed four or more people since 1966. Of the 88 shooters who met that criteria, only 14.8 percent had been diagnosed with a psychotic disorder. And even for them, it’s hard to say with any certainty that mental illness caused or contributed to their shooting.

The difference in the US is guns, not mental illness

Subsequent studies, both in the US and abroad, arrived at broadly similar conclusions to the 1980s ECA study that concluded only 4 percent of US violence is attributable to mental illness, even if the precise numbers were slightly different. “When we reviewed the literature, it varied between 3 and 10 percent in six studies,” Seena Fazel, a professor of forensic psychiatry at Oxford who has studied mental health and violent crime extensively, says, referring to a recent meta-analysis he and colleagues conducted. “But none of these was in the US.”

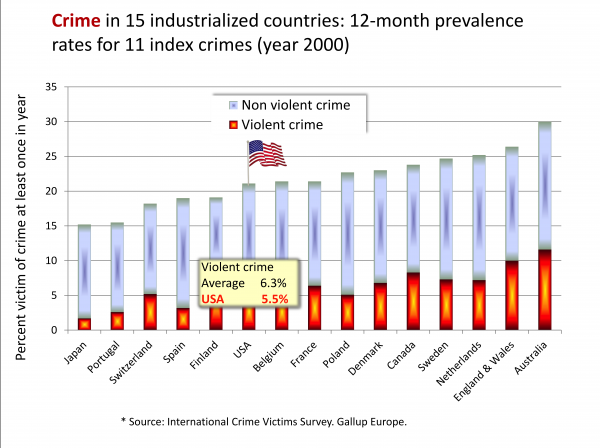

The US and other countries are more similar when it comes to violence than you might think. Most crimes, even most violent crimes, aren’t any more common here than in other countries. You see that in crime victim surveys (like the one highlighted in the above chart, which Swanson created) as well as in official government crime statistics. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s collated government data, the crime of assault was rarer in the US in 2014 than it was in Australia, France, Ireland, or the Netherlands. The assault rates in Belgium and England/Wales were more than double the US rate. Some of that is due to differing assault definitions, but scholars generally agree that for most offenses, US crime rates are pretty normal.

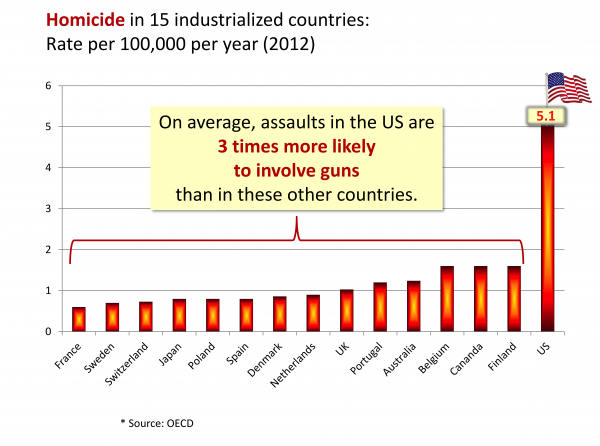

The one huge, glaring exception is homicide:

The difference isn’t that mental illness is more prevalent in the US than in other countries. It’s not even that the US has worse access to mental health care — that’s true, but it’s hard to see why it would lead to more homicide but not more of any other violent crime in the US.

Instead, a major factor is that the US has a lot more guns floating around. Swanson offers an example: “Imagine three immature, impulsive, intoxicated young men who come out of a pub in the UK in the middle of the night and get into an argument. There, somebody gets a black eye and a bloody nose. In one of our big cities, it’s statistically more likely someone has a firearm, so you’re likelier to get a dead body.”

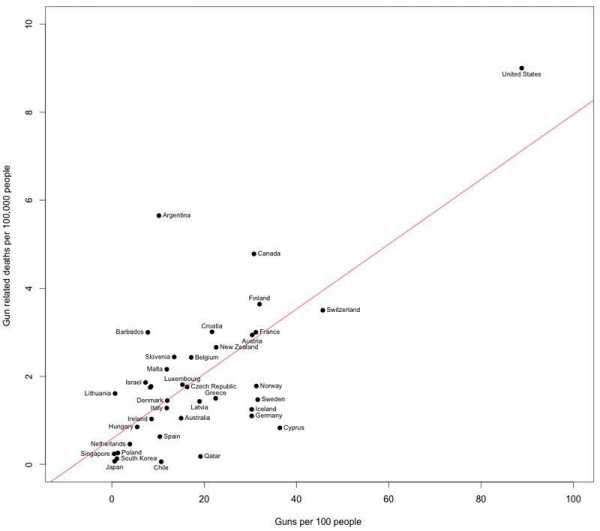

Sure enough, international data shows that countries with higher gun ownership rates have more gun deaths:

And similarly, US states with higher gun ownership levels see more gun deaths, including gun homicides.

America has a critical mass of angry people with guns

Swanson, the Duke University researcher, is not a fan of broadly forbidding all mentally ill people from owning guns. But he still thinks there’s a high-risk segment of the population it would be useful to target.

In a 2015 paper, Swanson, Harvard’s Ronald Kessler, and five co-authors sought to identify how many Americans show a pattern of impulsive angry behavior. So they looked at data from a survey that just asked people. Specifically, it asked if they agreed with one of three statements:

- “I have tantrums or angry outbursts.”

- “Sometimes I get so angry I break or smash things.”

- “I lose my temper and get into physical fights.”

We don’t know with certainty that this group is likelier to impulsively use firearms. But it stands to reason they would be.

About 8.9 percent of Americans, the study found, report one of these behaviors and have a gun at home; that’s roughly 22 million adults. And 1.5 percent (3.6 million) report one of the behaviors and carry guns with them outside the house. “Fewer than 10 percent have ever been in a hospital for mental health or substance abuse,” Swanson says. Barring people with severe mental illness from getting guns isn’t going to reach this population.

What could, Swanson argues, are extreme risk protection order laws. Those laws, passed in Connecticut in 1999, Indiana in 2005, Washington and California in 2016, Oregon in 2017, and an astonishing 10 additional states in 2018 and 2019 alone, offer legal avenues for police to seize guns temporarily from people determined to be a danger to themselves or others.

The laws typically require a judge to approve the order on the basis of evidence offered by police or a concerned family member; it can last up to a year. That could, in theory, let concerned friends and family flag impulsive and angry people of the kind Swanson’s research identified and keep them away from guns. Unlike restrictions on gun sales, it would apply to people already in possession of guns.

And the people affected tend to have a lot of guns — seven each on average, according to a study by (yes) Swanson and nine co-authors focusing on Connecticut’s experience. The study found that the law was most often used to take guns away from people at risk of suicide, not homicide. Since most gun deaths are suicides, and guns are a much more lethal tool of suicide than just about anything else, that saved a significant number of lives. About 44 percent of people who had their guns taken away received psychiatric treatment they weren’t getting before.

The study estimates that the law prevented one suicide for every 10 to 20 removals carried out. Whether or not that’s a good deal depends, naturally, on how you weigh gun rights against the cost to human lives. But it’s indicative of effectiveness on suicides.

As for homicide or mass shootings, the law’s effect is less clear and evident. It didn’t, and likely couldn’t have, stopped Adam Lanza from killing 26 people in Newtown, Connecticut, because Lanza used his mother’s guns rather than ones he bought himself. And while it stands to reason that taking guns away from angry people would reduce homicides or mass shootings, we have little concrete evidence that the angry people Swanson’s research has identified are likelier to commit violent crimes or how much likelier if so. It’s an area begging for more research.

But Swanson thinks it’s a better place to be looking than the mentally ill as a whole. “What if the president had said, instead of, ‘This is a mental illness thing,’ that [the Texas church shooter] was a veteran, this is a veterans’ problem, ban guns for all the veterans”? he asks, referring to the Sutherland Springs, Texas, shooting from November 2017. “That would be outrageous. … We need to understand risk for what it is and not just assume punitively that this whole huge category of people is risky.”

Further reading:

- While mental health isn’t the key to the gun homicide problem, most gun deaths are suicides, and better mental health treatment and gun control are both effective at combating that larger problem.

- Olga Khazan has an excellent overview of the evidence on mental health and mass shootings at the Atlantic.

- Michael Rosenwald at the Washington Post digs into research on why Americans stereotype the mentally ill as violent, despite countervailing evidence.

- Laura Hayes explains the connections between anger and violence at Slate.

- Ari Ne’eman here at Vox makes the disability rights case against restricting gun rights for people with mental illness.

Sourse: vox.com