On July Fourth, Rep. Justin Amash declared his independence from the Republican Party. The Congress member from Michigan had long been a thorn in the side of his party’s leadership. A libertarian-leaning conservative, he harbored the mistrust of Donald Trump that you’d expect from, well, a libertarian-leaning conservative. Amid damning evidence that the president of the United States had broken the law and obstructed justice, he asked for an impeachment inquiry. In return, he got a primary challenger.

“I’ve become disenchanted with party politics and frightened by what I see from it,” Amash wrote in the Washington Post. “The two-party system has evolved into an existential threat to American principles and institutions.”

If conservatives believed what they claim to believe about executive power and limited government and congressional primacy, they would have seen Trump’s presidency as a crisis. And for some, like Amash, it was. George Will, the longtime columnist at the Washington Post, left the Republican Party, arguing that Republicans needed to be “stripped of the Constitution’s Article I powers that they have been too invertebrate to use against the current wielder of Article II powers.” Rep. Mark Sanford, the rock-ribbed conservative from South Carolina, refused to hold his tongue and lost to a primary challenger.

But for most conservatives, whether they were prominent pundits or everyday voters, there proved to be no contradiction between conservatism and Trumpism. Quite the opposite, actually. According to Gallup, 73 percent of self-identified conservatives and 94 percent of self-identified conservative Republicans approve of the job Trump is doing. This is because conservatism isn’t, for most people, an ideology. It’s a group identity.

A clever 2018 paper by political scientists Michael Barber and Jeremy Pope tested this experimentally. Trump was constantly adopting contradictory positions on issues, and his reputation for saying and doing anything primed voters to believe he really had said whatever you told them he’d said. “There has never been a president (or any party leader) who shifts back and forth so often between liberal and conservative issue positions,” they wrote, and that opened space for a revealing study.

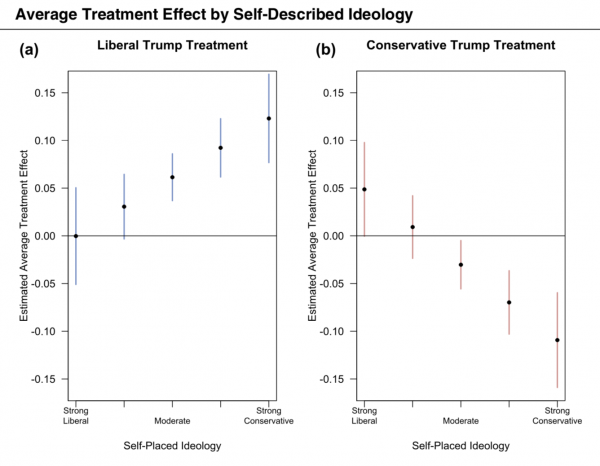

Here’s how it worked: Barber and Pope asked voters if they agreed or disagreed with different policies. Because of the, erm, flexibility of Trump’s rhetoric, they were able to pick policies where Trump had, at some point, taken both a liberal policy position and a conservative policy position. And so some voters were asked about the policy without a cue telling them what Trump thought, but other were asked about the policy and given either Trump’s liberal position on the policy or his conservative one.

The idea here was to see how much of a difference Trump’s positioning made, and to whom. Among the most interesting findings is in the chart below. The people who identified as most strongly conservative were the likeliest to move in response to Trump. And the effect was about the same size whether Trump was taking the conservative or liberal position. It was the direction of Trump, not the direction of the policy, that mattered. Interestingly, there wasn’t an equal and opposite reaction among strong liberals: They didn’t change position much to oppose Trump.

“The fact that stronger conservatives are the ones most likely to react to the treatment — regardless of the ideological direction of the treatment — suggests that the nearly ubiquitous self-placed ideology measure is less a measure of principled conviction and more of a social identity,” write Barber and Pope.

It’s worth dwelling on that idea for a moment. One way to think of conservatism is as an ideology, a philosophy that exists separate and apart from politicians and political parties. Another way to think of it is as a social identity, in which being a conservative means identifying with the group of people who call themselves conservatives.

What Barber and Pope figured out was a way to test that precise question. If conservatism was an ideology first and foremost, then a stronger attachment to that ideology should provide a stronger mooring against the winds of Trump — in their formulation, you should see more “policy loyalism” and less “party loyalism” among people who saw themselves as committed conservatives. Instead, “we observe exactly the opposite: strong ‘conservatives’ are the most likely to be partisan loyalists — following Trump in a liberal direction when told of his support for a liberal policy.”

What this experiment suggests — and what Amash, Sanford, and other philosophically conservative politicians have found — is that the Republican form of conservatism is first and foremost an identity group. That identity group sees Trump as their champion, and his critics, be they left or right, as threats to the group’s interests.

Shortly before he left Congress, I sat down with Mark Sanford for an episode of my podcast. I asked him how his constituents expressed their anger at him for his criticisms of Trump. His reply has stuck with me. “People would come up and they say, ‘Look, he’s the quarterback. You got to go with the quarterback.’”

Amash made a similar point in his interview with my colleague Jane Coaston:

This is a way in which our political language fails us. The terms we use to describe ideologies are often describing social identities. And what matters to an identity group is whether their group is winning or losing. Trump understood this better than most. He’s always framed his political project as about winning rather than about conservatism, and he’s been proven right again and again and again.

Sourse: vox.com