My old American Prospect editor Mark Schmitt had a maxim I always liked: “It’s not what you say about the issues; it’s what the issues say about you.”

Mark’s line came to mind while I was interviewing Elizabeth Warren (you can listen to our conversation on my podcast, or read it here). I’ve seen a lot of nervous Democrats compare Warren to Hillary Clinton. After all, Clinton had plans too. Clinton was the most prepared candidate on the stage, too. And look how that ended.

d=”pbqQ8T”>I think the analogy is flawed. Clinton had a lot of plans but no clear message. Warren’s genius has been to turn a lot of plans into a clear message. Clinton’s plans couldn’t dispel the sense that she was complicit in the status quo. Warren’s plans underscore her longstanding loathing of what American capitalism has curdled into.

It’s common for Democrats to talk about income inequality. Warren fixates on wealth inequality. During our conversation, she used the word “wealth” 23 times but mentioned “income” only four times. There’s a reason for that. Wealth is where income pools into power and privilege. When your money comes from income, it is, at least in theory, being earned through work. When it’s just wealth creating more wealth, it’s a hoarding of resources divorced from the labor and innovation that drives economies forward.

“Think of it this way,” she told me. “The bottom 99 percent last year paid all-in on their taxes 7.2 percent of their total wealth. Top 1 percent? They paid 3.2 percent of their total wealth.” Those huge fortunes, she continued, “are growing on their own. They are now capital. You don’t have to work if you’ve got one of those big fortunes. Those things are managed by professional managers.” Listen to how Warren talks about this. It offends her.

Over and over again, Warren turned the conversation back to her wealth tax, and everything it could buy. Like here:

And here:

And here:

Warren’s tagline is “I have a plan for that.” And on one level, it’s true: She has a lot of plans. But a clearer way of understanding her pitch is she’s got one plan that she applies over and over again.

As Warren sees it, there’s been a massive hoarding of wealth — and thus of power and opportunity — in this country. She wants to tax the wealth and redistribute both the money and the opportunity. She wants to break up concentrations of economic power by putting workers on corporate boards and unleashing antitrust regulators on Amazon and Facebook and ending Washington’s revolving door. These are different policies, yes, but they all say the same thing: The wealthy have too much money and power, and Warren wants to change that.

That’s the difference between her and Clinton. Clinton had a lot of plans and just as many messages. Warren has a lot of plans, but they reinforce one message. Warren has her weaknesses, but the way she talks through policy is a defining strength.

A few other notes from our conversation:

• I asked Warren where she disagreed with the democratic socialists, and didn’t get much. “I believe in markets,” she told me. “But markets without rules are theft.” I asked her about health care and education, which are the only places where Bernie Sanders suggests nationalizing even part of an industry, but Warren agreed with him. “Markets mostly don’t work in those areas,” she said. “It’s not to say there aren’t pieces that you could make work, but no. Health care is something that is a basic human right, and we fight for basic human rights. Public education is public education because it’s not market-driven.”

Sanders calls himself a democratic socialist and Warren calls herself a capitalist, but the difference between them is subtler than that suggests. If you ask Warren about capitalism, she’ll wax rhapsodic about what properly regulated markets can create. Ask Sanders about capitalism and he’ll focus on its failures and fundamental immorality. It’s a sharp difference in affect, but it doesn’t lead to all that much difference in policy.

• A more serious split in the primary is between Warren and Joe Biden’s theories of change. Biden is emphatic that the problem is the politicians, not the political structure. “The system’s worked pretty damn well,” he says. “It’s called the Constitution. It says you have to get a consensus to get anything done.”

Biden pitches himself as likelier than his competitors to get that consensus. Warren, by contrast, holds no illusion that she’ll receive Republican support, and is all about systemic change. She told me her first bill would be a massive anti-corruption package. She wants to persuade her fellow Democrats to abolish the filibuster. “This business that Democrats play by one set of rules and Republicans play by a different set of rules — those days are over when I’m president,” she says. “We’re not doing that anymore.”

• When I asked Warren what she’d do first as president, she answered quickly. “I’ll do the things that I can do as president on my own.” For all her enthusiasm for executive action, I found her a little vague on the authorities she’d use. But while most presidents delegate regulation to staff, having watched Warren’s career, I think she’s unusually likely to act as regulator-in-chief.

Warren designed and helped construct an aggressive regulatory agency — the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau — and she did it well. As a senator, she’s put a particular focus on fighting over regulatory decisions and appointments. She has expertise here that most presidential candidates don’t. “You know, most of those agencies were built at a time when we believed in government,” she told me. “That was true whether you were talking about the Food and Drug Administration or the Department of Commerce or the Environmental Protection Agency. Those agencies still have a huge number of tools.”

Presidential campaigns tend to focus on legislative dreams rather than regulatory strategies, but it’s very likely that even if a Democrat wins in 2020, they will face a Republican Senate. In that world, the ability to creatively wield the powers of the executive branch will matter enormously. I’d like to see Warren, and all the Democrats, get more specific on how they’d approach this part of the job.

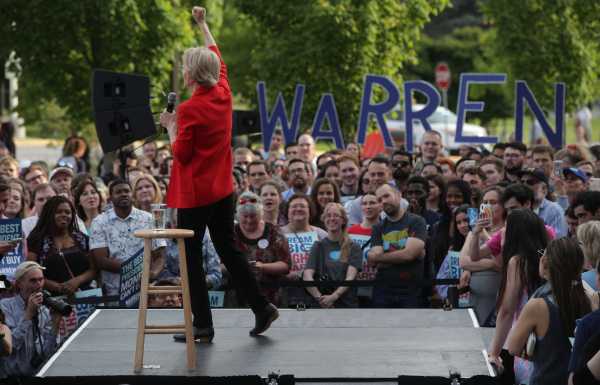

• This one is more impressionistic, but there’s enough of a narrative out there that I want to say it: I’ve interviewed most of the Democrats running for president and I find Warren warmer and more natural than almost any of them. That’s true in person, but it’s also true on the stump.

This bit got cut from the transcript, but if you listen to our full podcast, you’ll hear her discussing her insistence that the lights are always turned up in the auditoriums so she can see the faces of her audience and actually interact with them. “It’s actually a very close and intimate interaction, even with a thousand people or a couple of thousand,” she says. “It’s the eye to eye, face to face.” This isn’t just talk: Warren engages much more naturally with the crowd than most politicians do. The idea that she comes off as cold or uncharismatic on the stump — she was going viral with speeches when that was barely a thing — crumbles upon watching or meeting her.

That said, Warren has never performed that well in Massachusetts. She ran behind Barack Obama in 2012 and, adjusting for the swing toward Democrats from 2016 to 2018, behind Hillary Clinton too. She’s less popular than Charlie Baker, the Republican governor. She’s trailing Biden in her own state. This is the “electability” question that I wonder about with Warren — why isn’t she stronger among the voters who know her best?

Correction 6/14: An earlier version of this article misstated Warren’s role at the CFPB.

Sourse: vox.com