For the first time ever, women in their 30s in the US are having more babies than women in their 20s, according to recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That’s significant because older women can have much more difficulty recovering from pregnancy and childbirth than younger women. And most women, regardless of their age, receive poor postnatal care in the critical first 12 weeks after birth known as “the fourth trimester.”

In fact, postnatal care is one of the most under-discussed and under-studied issues in medicine. (One reason, among many, that more American women today are dying in childbirth than anywhere else in the developed world.)

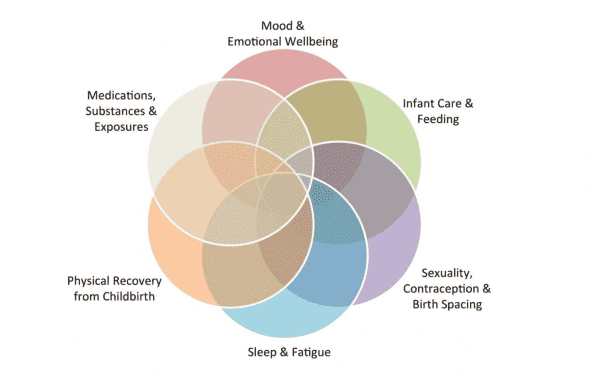

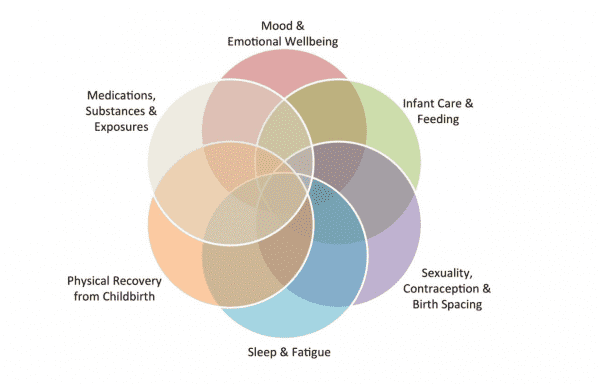

Lately, though, we’ve begun to learn about the experiences of postpartum women, thanks to the 4th Trimester Project, a groundbreaking study led by a team of doctors and researchers at UNC Chapel Hill. For two years, they have been following postpartum women and health care providers to learn how new moms are served — and how health care for them could be better.

Strikingly, they’ve found that new moms very often aren’t aware of possible complications, are too embarrassed to discuss their symptoms, and have no clue there are treatments that could help them. They get just one medical visit six weeks after birth, and that’s often woefully insufficient for the issues they’re dealing with.

It’s worth diving in to understand why women deserve much better than what they’re getting.

The typical postpartum symptoms women experience can be severe

Isa Herrera, a New York City physical therapist specializing in pelvic pain, says new moms are often unprepared for the aftermath of childbirth. “There’s this fantasy. Your body is going to come back together. Your organs are going to be in place. It’s an illusion,” she told me.

Among the typical symptoms women face in the first week after childbirth: heavy bleeding, abdominal cramping, constipation, hemorrhoids, chills, night sweats, difficulty going to the bathroom, engorged breasts, back pain, headaches. And it goes on: pain in the perineum (the diamond shaped sling of muscles in the pelvis), incision pain (if the woman has had a C-section), pain and difficulty walking (after an episiotomy or tear), depression, anxiety, and exhaustion.

Related

You lose friends when you have a baby, and other lessons I learned the hard way

About half of women who give birth are still in pain weeks later. More than 40 percent of women who delivered vaginally reported perineal pain, and nearly 60 percent who had C-sections experienced incision pain within two months of childbirth, according to a 2013 survey of 2,400 women, called Listening To Mothers, by the group Childbirth Connection. Nearly 80 percent of mothers surveyed said pain interfered with their daily activities. One in three reported urinary or bowel problems.

OB-GYNs and midwives who deliver babies don’t often find postpartum problems like nerve damage and incontinence because they aren’t looking for them. As Kari Bø, pelvic floor expert at the Norwegian School of Sports Science, explains, “Gynecologists, urologists and colorectal surgeons concentrate on their areas of interest and tend to ignore the pelvic floor common to them all.”

Rather than focusing on the “three holes in the pelvis,” practitioners owe it to women to see the “whole pelvis.” Since they don’t, pelvic pain or dysfunction often goes overlooked. Nearly a quarter of women have a pelvic floor disorder. The prevalence increases with each child a woman has.

Women aren’t told of more serious postpartum complications

In some instances, childbirth can cause more serious complications including hemorrhage, infection, incontinence, symphysis pubis dysfunction (pelvic girdle pain, which can be debilitating) and pelvic organ prolapse (when weak muscles allow organs to fall into the vagina).

With conditions like pelvic girdle pain and prolapse, women often think what they’re experiencing is normal, and don’t seek help until their condition worsens. Some 60 percent of postpartum women have a separation in their abdominal wall called Diastasis Recti, and plenty have weak or injured pelvic floor muscles, but haven’t heard of these things until related problems like pain or incontinence crop up.

According to Kristin Tully, a researcher with the 4th Trimester Project, women in the cohort weren’t aware of treatments that could help them, and were too embarrassed to discuss symptoms that medical professionals hadn’t brought up with them first. “Women didn’t know the range of what’s normal, when to seek guidance, and who to ask,” she said. Women don’t know about serious complications because their providers don’t always tell them.

Tully points out that postpartum women’s emotional wellbeing is also ignored by the current system. Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders like postpartum depression, anxiety, and psychosis have received more attention in recent years, but are still not always caught by doctors and nurses. Even when screening is universal, like it is in New Jersey, not all women who are tested get the help they need. Some 80 percent of postpartum women feel “baby blues,” according to one report. Postpartum depression affects one in seven women.

Postpartum health care in America is minimal to nonexistent

Moms are usually not the focus of attention after birth at the hospital. Alison Stuebe, an associate professor of maternal-fetal medicine at UNC Chapel Hill and a lead researcher on the 4th Trimester Project, says the focus is on the baby.

“Babies get NICUs [Neonatal Intensive Care Units] and mommies get, ‘Your blood pressure is high, why should we check it again?’” Stuebe said. “The baby is vulnerable and precious and has resources devoted to it, and American culture doesn’t appreciate that the mommy is recovering from a process.” This point was driven home in the recent ProPublica/NPR story about the death of a neonatal intensive care unit nurse 20 hours after her daughter’s birth.

The typical postpartum hospital stay is fewer than 48 hours. Women are usually sent home with ample resources about their babies and little guidance about how they can care for their own bodies, and how their partners, friends, and families might help them.

If women have problems after they are discharged from the hospital, they often don’t know who to call — their OB-GYN, the person who delivered them, their general practitioner, or hospital nursing staff? And their next official point of contact with health care system isn’t usually until more than a month later.

Routine postpartum care in America usually consists of just one visit with the doctor or midwife who delivered the baby at around six weeks after birth. During the appointment, practitioners perform vaginal and breast exams, check C-section incisions, and feel the uterus to ensure it has shrunk back to its pre-pregnancy size. They greenlight sex and exercise if things look good. They offer birth control. That’s pretty much it.

The women in the 4th Trimester study group reported receiving “didactic” one-size-fits-all information from doctors, “but they don’t talk to you.” The consequence of this, according to the research, is that the visit can occur too late to catch a complication. “Waiting [40 days] to check in doesn’t make sense,” Stuebe said. (Its origins may be in the Bible. Jesus was brought to the Temple at 40 days, and many cultures institute a 30 to 40 day lying in period for postpartum women to aid their recovery.)

How do other countries fare on postpartum care?

Many other developed countries allow women access to more care in the early days after birth, even in their own homes. France pays for perineal reeducation therapy, which helps women strengthen muscles to improve their overall vaginal health. It is also said to prevent problems that can arise even years after childbirth, like incontinence and sexual dysfunction. Switzerland and China offer new mothers longer hospital stays. In Europe, midwives commonly make house calls after birth to check up on women.

Some communities mandate a monastic existence for postpartum women — 30 to 40 days of rehabilitation and rest. In China, this period is called confinement, in Mexico, cuarentena. In both practices, new mothers are nourished with broths and wrap their bodies to ward off chills. Family members or hired help attend to their needs so that they can rest and feed their newborns.

In some places, the workplace is more flexible for new mothers. Nordic countries offer generous maternity leave that working moms can use to heal and care for their children. This is completely opposite from new moms’ experiences in America. Here, women return to work almost immediately — 23 percent of those employed go back just 10 days after they’ve given birth.

What better health care for women in the US after childbirth might look like

Herrera wants pelvic floor therapists at women’s hospital bedsides immediately after birth. Lactation consultants in pediatricians’ offices could help ease breastfeeding difficulties — moms are headed there anyway in the early days with their newborns. A variety of health care providers who see postpartum women could screen them for perinatal mood disorders. And pediatricians could also be available to new moms.

Related

Trump’s budget on health: 3 losers and 2 winners

One effective model Stuebe points to is the Monarch Centre in Ottawa, Ontario. It is an outpatient clinic that delivers many aspects of maternal and newborn care in one place — like lactation, physical exams and mental health — and sees women between 24 and 48 hours after they give birth.

The World Health Organization recommends that all postpartum women and babies receive three home visits from health providers as a routine part of care. This model has been adopted in Durham, North Carolina, where the grant-funded program Durham Connects provides all women who give birth in the city home visits. Director Ben Goodman said that of the 10,000 moms the program has seen since 2009, 95 percent “have some level of nurse-identified risk or need” during the fourth trimester.

These solutions may seem obvious, but they are not common. Understanding that a fourth trimester is only a starting point. “In an ideal world women would get home visits or their family members would get paid leave to attend to them,” Stuebe said. “If we’re not going to have that, we need some touchpoint from the health care system to replace that village that is no longer part of our culture.”

Allison Yarrow is a journalist and author living in Brooklyn. Follow her on Twitter @aliyarrow.

Sourse: vox.com