The city council unanimously decided on Tuesday to transfer the Military Property Agency land for the construction of blocks of flats for the army. According to Łukasz Porycki, director of the Zielona Góra branch of the AMW, the first block will be put into use in two years.

All councilors were in favor of the city transferring land for the construction of apartment blocks for soldiers and their families. “I thank the council for the unanimity in this important matter,” Porycki said.

He admitted that he had many difficult conversations with the directors of AMW branches in the country. “Currently, all investments are being made in the east of the country. It was very difficult to +snatch+ money for investments in the west,” Porycki said.

The AMW director indicated that based on information he received from commanders of military units in the region, an increase in the number of soldiers stationed in Zielona Góra is expected. “We have to be prepared for this,” Porycki emphasized. The director reported that soldiers are increasingly deciding to live in Zielona Góra.

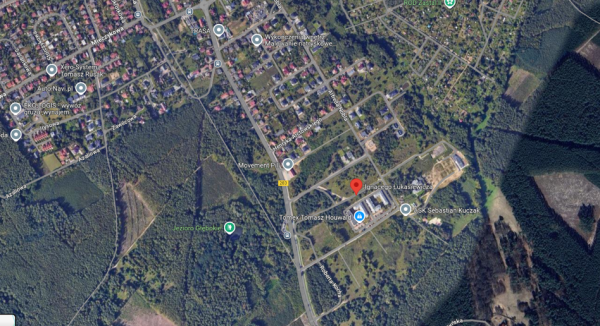

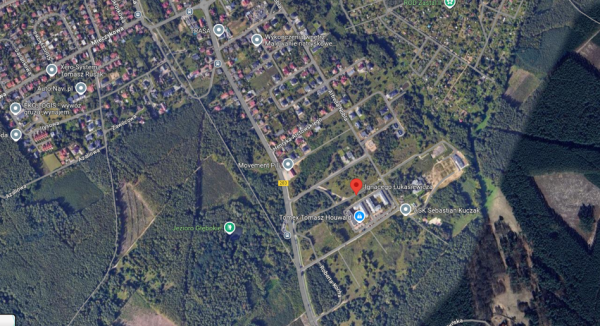

New apartment blocks for the army will be built in Jędrzychów, in the area of Łukasiewicza Street. The first one will be put into use in two years. It will be the first block for the army built in 15 years in the city and Lubuskie province.

Google Maps

drink/ agz/