England’s galacticos of Luke Humphries and Michael Smith win the World Cup of Darts for the first time since 2016; Darts is back on Sky Sports with the World Matchplay from Saturday, July 13 on Sky Sports Arena

Check out the best of the action as Luke Humphries and Michael Smith were on fire for England as they ended an eight-year wait to win the World Cup of Darts

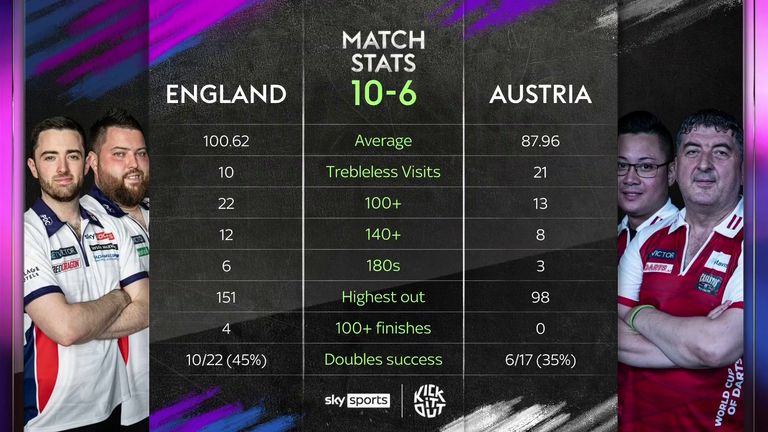

The dream team of Luke Humphries and Michael Smith gave England a record-breaking fifth World Cup of Darts title and first since 2016 with a 10-6 victory over Austria.

World Cup debutant Humphries and 2023 world champion Smith delivered the goods to secure England’s first World Cup triumph in eight years.

Phil Taylor and Adrian Lewis were the only players to have lifted the World Cup title for England since the tournament’s inception in 2010, but Humphries and Smith created their own history with a dominant success on German soil at the Eissporthalle in Frankfurt.

World Cup of Darts – Results

| Quarter-finals | Austria | 8-7 | Croatia |

| Belgium | 8-7 | Italy | |

| England | 8-4 | Northern Ireland | |

| Scotland | 8-7 | Sweden | |

| Semi-finals | Austria | 8-4 | Belgium |

| England | 8-3 | Scotland | |

| Final | England | 10-6 | Austria |

- Stream the Darts and more with NOW

- How England won the World Cup for a fifth time…

- Barry Hearn: Luke Littler effect puts Ally Pally future ‘under discussion’

- Luke Littler: I proved doubters wrong on ‘best night of my life’

Luke Humphries and Michael Smith celebrate winning a record-breaking fifth World Cup of Darts for England

“I felt the biggest buzz since winning the Worlds. We really wanted this. We really believed we could win it and after that first game we played, we clicked,” Humphries told Sky Sports.

“You’ve got a cheat code, the world number one and number three against the field, it’s quite tough for everyone else but after that first game we played and we clicked. We were only worried about ourselves. We knew if we played our best, we could do it and we did.

“I just hope we get to come back next year and defend it together as champions.”

Humphries and Smith share their thoughts after their World Cup of Darts triumph against Austria

Smith was full of praise for team-mate Humphries, adding: “How good was this man in the final? He hit everything.

“My [double] tops was non-existent and every single shot I left him, bang, bang, bang…. thank you so much mate, you’ve just got me the gold medal.”

The title favourites raced into a 5-1 lead over 2021 runners-up Rowby-John Rodriguez and Mensur Suljovic, Humphries taking out 151 in the sixth leg and 121 in the next before Austria hit back to reduce their deficit to 6-4.

A 180 from Humphries then set up Smith, who had struggled with his doubles early on, to take out double 15 before finishes of 130 and 112 from Humphries took England to the brink of victory.

Suljovic took out 98 to keep the match alive but Smith sealed the win on double eight in the next leg.

Humphries slammed in FOUR ton-plus checkouts in the final

England deserved to be crowned champions

“No one has got within four legs of England, they’ve been that dominant,” said Mark Webster, a 2010 World Cup of Darts finalist for Wales.

“They were pushed in that final but they just all the answers including those big finishes from Luke Humphries.

“They functioned as a team throughout. They were heavy favourites and lived up to it. They’re deserved champions.”

Twitter This content is provided by Twitter, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Twitter cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Twitter cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Twitter cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

Tale of the Tape

World Cup of Darts: Roll of Honour

England had earlier beaten Northern Ireland 8-4 in the quarter-finals and Scotland by the same score in the last four with Gary Anderson riled by referee Kirk Bevins having stepped over the oche throwing his final dart leading to confusion.

Bevins later took to social media to defend his decision, explaining on X: “Darts referees make judgment calls based on what we see at the oche. If someone is throwing a dart away while walking, the referee has to make a quick decision. If you want every dart to count, make sure both feet are behind the oche rather than walking and relying on VAR.”

Austria edged past Croatia 8-7 in the quarter-finals before an 8-3 win over Belgium in the semis.

Referee Kirk Bevins ruled that Gary Anderson stepped over the oche throwing his final dart leading to confusion in Scotland’s semi-final against England Twitter This content is provided by Twitter, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Twitter cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Twitter cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Twitter cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

What’s next on Sky Sports?

The 2024 World Matchplay starts July 13th , only on Sky Sports!

The 2024 Betfred World Matchplay will take place from July 13-21 at the Winter Gardens, Blackpool.

The iconic summer tournament will see 32 of the world’s top stars battling it out across nine days for the Phil Taylor Trophy and £800,000 in prize money.

- Darts in 2024: Key dates and winners from Premier League and more

- Get Sky Sports | Get Sky Sports on WhatsApp

- Download the Sky Sports App I Follow @SkySportsDarts

2024 Betfred World Matchplay

Schedule of Play

Saturday July 13 (7.30pm)

4x First Round

Sunday July 14 (1pm)

Afternoon Session

4x First Round

Evening Session (7pm)

4x First Round

Monday July 15 (7pm)

4x First Round

Tuesday July 16 (7pm)

4x Second Round

Wednesday July 17 (7pm)

4x Second Round

Thursday July 18 (8pm)

2x Quarter-Finals

Friday July 19 (8pm)

2x Quarter-Finals

Saturday July 20 (8pm)

Semi-Finals

Sunday July 21 (1pm)

Afternoon Session

Women’s World Matchplay

Evening Session (8pm)

Final

Ad content | Stream Sky Sports on NOW

Stream Sky Sports live with no contract on a Month or Day membership on NOW. Instant access to live action from the Premier League and EFL, plus darts, cricket, tennis, golf and so much more.

Sourse: skysports.com