Nunez pocketed by Pepe

Image: Darwin Nunez was pocketed by Pepe as Uruguay failed to score against Portugal

Is there a more frustrating player to watch than Darwin Nunez? He’s got it all. Yet blows so hot and cold.

To coin a classic Paul Merson phrase, Darwin Nunez is like a bag of Revels. One day he’s a delicious toffee – so succulent and silk. One day he’s a sickly coffee chocolate – getting marked out of the game by a 39-year-old Pepe for Portugal, who became the third-oldest outfield player in World Cup history by replacing the injured Danilo.

- Portugal 2-0 Uruguay – Match report and ratings

- How the teams lined up | Match stats

On paper the match-up looked a potential fertile area for Uruguay to exploit. Nunez – an £80m striker in his prime – up against a man who turns 40 in February playing without much defensive cover around him. However, Uruguay failed to exploit the obvious pace of Nunez. Yes, the service into him was nor up to standard but Nunez did not help his cause with a sketchy technical performance where his – and Edinson Cavani’s – hold-up play in attack continually meant Uruguay had no platform in the game. It was not until Nunez and Cavani were hooked with their team chasing an equaliser that Uruguay started to expose the flaws in the Portugal backline.

Uruguay now have a must-win clash with Ghana to keep their World Cup dream alive. Nunez may have to watch that from the bench judged on this showing.

Lewis Jones

Trending

- World Cup 2022 schedule, group tables and last-16 draw

- Agnelli and entire Juventus board resign

- Papers: Chelsea close on Nkunku | Beckham to bid for Man Utd

- Protester with rainbow flag invades pitch at World Cup

- FA Cup third-round draw: Man City host Chelsea, Man Utd vs Everton

- Southgate on squad rotation: It’s a World Cup, we can’t just give caps out

- Fernandes’ double sends Portugal into last 16

- Transfer Centre LIVE! Nkunku ‘close’ to Chelsea | Neville hails Ronaldo response

- World Cup hits and misses: Nunez pocketed by Pepe as Bruno shines

- Reporter notebook: Tensions between USA, Iran make for ‘strange’ build-up

- Video

- Latest News

Fernandes takes centre-stage for Portugal

Image: Bruno Fernandes celebrates after doubling Portugal’s lead from the penalty spot

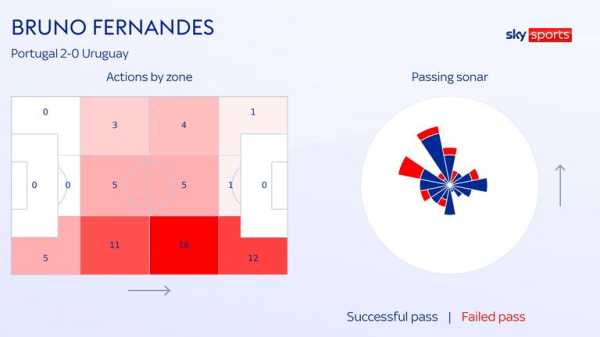

The debate over Cristiano Ronaldo’s phantom touch on Bruno Fernandes’ cross for Portugal’s first goal against Uruguay will attract plenty of attention. But the fact that it goes down as a goal rather than assist does not alter Fernandes’ crucial role in it.

The Manchester United midfielder went on to score the second goal from a penalty that he had won. Add these goals to the two assists that he provided for his team-mates late in the win over Ghana and Fernandes might just be the player of the tournament so far.

Also See:

Image: Despite playing from the right, Bruno Fernandes popped up on the left to score a crucial goal

He is the only man to score twice and assist twice. Nobody has been involved in more goals. It has not always been fluent but Fernandes is finding moments. All this from a player who it was said could not function at his best for club or country when Ronaldo is around.

That eve-of-tournament interview that led to Ronaldo’s United exit provided the backdrop and the national team was engulfed in the fall out. A video of Fernandes appearing to shun Ronaldo fuelled the chatter. But every World Cup success story has its setbacks.

Portugal are through to the knockout stages with a game to spare. They are likely to progress as Group H winners and can expect to be favourites to reach the quarter-finals. A World Cup that began with fuss over his relationship with Ronaldo could yet end in glory.

Adam Bate

Aboubakar does his talking on the pitch

Image: Vincent Aboubakar changed the game for Cameroon

Cameroon were hurtling towards a record-equalling ninth straight defeat at a World Cup finals when Aleksandar Mitrovic completed a fine team goal for Serbia just eight minutes into the second half at the Al Janoub Stadium.

Manager Rigobert Song loooked out of ideas but that was the cue for Vincent Aboubakar to come off the bench. Cameroon changed to a 4-4-2 formation with Aboubakar, who top-scored at the Africa Cup of Nations finals earlier this year, partnering Eric Maxim Choupo-Moting up front.

- Cameroon 3-3 Serbia – Match report and ratings

- How the teams lined up | Match stats

It would prove a switch that would turn this roller-coaster Group G fixture on its head. First he provided a perfect chip into the net for 3-2, then he beat the offside trap, raced clear and whipped over a low cross for Choupo-Moting to level the tie and keep Cameroon alive in the competition.

Aboubakar became the first substitute to both score and assist a goal in a World Cup match for an African nation.

Image: Aboubakar scores with a stunning lobbed finish

Earlier this month, the striker who plays in Saudi Arabia for Al Nassr, claimed the only difference between him and Mohamed Salah is the Liverpool forward has the chance to ‘play in a big club’.

Aboubakar told 90FootballFr: “I’m not impressed by him. I can do what he does. I just don’t have the opportunity to play in a big club. I understand people’s attitudes, he’s one of the best goalscorers in the Premier League. It makes sense that when you go on about a player like that, people will talk.

“But I did say that it was my opinion, my point of view. I don’t give a toss if people don’t like it.”

Having been left out by Song against Switzerland, Aboubakar made his point on the perfect stage. Cameroon’s best chances of conquering Brazil in their final game will involve playing him from the start.

Ben Grounds

Tite harnesses Brazil’s attacking gems to stay perfect

As had been the case in their opening win over Serbia, Brazil were made to wait against Switzerland.

For a long time, without talisman Neymar, they struggled for any sort of fluency in attack and, when they were able to establish control in the final third, they were met with a wall of red shirts that restricted their esteemed opponents’ opportunities.

During half-time at Stadium 974, though, head coach Tite knew he had to introduce fresh blood onto the pitch. New ideas were needed as the threat of a Swiss sucker-punch lingered and grew.

- Brazil 1-0 Switzerland – Match report & ratings

- How the teams lined up | Match stats

Real Madrid’s Rodrygo came on and, within 20 minutes, he was involved in the move that concluded with Brazil having the ball in the net through domestic team-mate Vinicius Jnr, though it would soon be chalked off for offside.

Later, on came Manchester United’s Antony and Arsenal’s Gabriel Jesus for Raphinha and Richarlison. The strength in depth at Tite’s disposal is extraordinary – and, in the end, he harnessed it to perfection.

Vinicius and Rodrygo intuitively linked up, combining for Casemiro to slam home the winner that keeps Brazil perfect and makes them just the second nation, after France, to qualify for the last 16.

Sky Sports’ Gary Neville was impressed by the way Tite eventually utilised his attacking players, too. Speaking on ITV, he said: “He didn’t have enough [of his attackers] on the pitch at the start of the game but towards the end it looked the right type of balance for the quality they have.”

“And they’re now in a brilliant position where they’ve not only [qualified] but all those talented players, we could see them in the third game.”

It’s a frightening thought.

Dan Long

Admirable risk with backs against wall

Cameroon threw caution to the wind with their backs against the wall.

Rigobert Song’s side looked down and out after an intra-team fall-out, pressure from above and a couple of goals conceded right at the end of the first half. It could have got messy but the Cameroonians had other ideas.

It was a nervy start for Cameroon, who hosted the Africa Cup of Nations earlier this year, with elements of desperation falling into their game from the first whistle. Serbia looked sharp and could have ripped Cameroon apart early doors if they had taken their chances.

- World Cup results | Fixtures | Group tables

- Full schedule for Qatar 2022 | World Cup team guides | Download the Sky Sports App

Yes, they scored a goal against the run of play. But any momentum gained from confidence disintegrated in a matter of minutes. The half-time team-talk would have been vital.

Cameroon proceeded to risk it all – they had nothing to lose. On came another striker in Vincent Aboubakar. The second half was a case of fire fighting both sides pushed high up the pitch.

Intriguingly, as you can see in the graphic below, the game seemed to play out on the same side of the pitch – you would be disappointed if you were sat on the other side of the stadium.

As pressure mounted in this must-win match, Song could have instructed his side to defend deeper, hoping to catch Serbia on the counter. Instead, he went for goals in a fearless approach, for which he should be praised.

While it was a tactic that led to Serbia scoring a third, it also created opportunities for the African team to score a quick-fire double – snatching a draw from a superior Serbia side on the day – in terms of possession in the final third.

Cameroon failed to secure three vital points and may well be on their way out of the World Cup, but the spirit they showed in the face of adversity reminds you why you love the beautiful game: anything happens… and it usually does.

Adam Williams

Serbia failing to match dark horses tag

Image: Aleksandar Mitrovic opened his World Cup 2022 account against Cameroon but also missed several chances

After finishing above Portugal in qualifying and arriving at the tournament with Aleksandar Mitrovic, Dusan Vlahovic and Sergej Milinkovic-Savic in their ranks, it’s not hard to see why Serbia were tipped by many to be dark horses at the World Cup.

However, despite scoring three times against Cameroon on Monday, Serbia find themselves bottom of Group G with just one point after two matches thanks to some shambolic second-half defending.

All is not lost for Dragan Stojkovic’s side but they will now need to beat Switzerland in their final game on Friday to stand any chance of reaching the last 16 for the first time as an independent nation.

But their defensive record so far in Qatar must be a concern, with Serbia – who had only conceded 20 goals in 21 games under Stojkovic – now shipping five in just 180 minutes of football.

The two horrendously executed offside traps that allowed Vincent Aboubakar to score Cameroon’s second goal and set up their third were particularly puzzling – as was the failure to introduce Dusan Vlahovic as they chased a winner.

The Juventus striker has six goals in 10 Serie A games this season and has been one of the most productive forwards in Italy in recent years, but has been handed just 24 minutes of football in Qatar, all of which came against Brazil.

The pairing of Mitrovic and Vlahovic – with a combined 60 goals in 88 international games – was deployed several times in qualifying but Stojkovic has appeared reluctant to do so in Qatar.

But with victory against Switzerland essential, the time has surely come to hand Vlahovic his first start of the tournament, while Stojkovic will no doubt be drilling his back-three in training this week.

Joe Shread

Kudus to Ghana

Image: Mohammed Kudus wheels away after restoring Ghana’s lead against South Korea

Heading into their Group H clash with South Korea on Monday, Ghana knew that defeat at the Education City Stadium would see them exit the competition after just two games, which meant the pressure was well and truly on Otto Addo’s side.

Twitter Due to your consent preferences, you’re not able to view this. Open Privacy Options

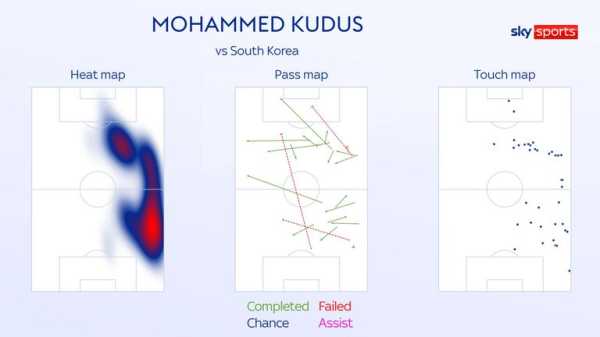

Luckily, though, Mohammed Kudus picked the ideal time to make Ghanian football history after the Ajax midfielder headed his team into a 2-0 half-time lead, before then sealing a 3-2 win with a composed finish midway through the second period.

- Ghana 3-2 South Korea – Match report & ratings

- How the teams lined up | Match stats

As a result, the 22-year-old became the first Ghana player to score two goals in a World Cup match, while he also became the second youngest African player to net twice in the competition.

That double means Ghana’s World Cup fate is now in their own hands ahead of their final clash with Uruguay on Friday.

Richard Morgan

A quiet World Cup for Son?

Heung-Min Son is one of the most devastating forwards in world football, and his appearance in the World Cup despite damaging his eye socket in the same month has been remarkable. The issue is, he has not really led the South Korean line as we know he can.

Son is known worldwide for his ability to make and score goals for Tottenham alongside his partner in crime Harry Kane. However, neither of them has scored in this World Cup while they captain their respective nations.

South Korea drew 0-0 with Uruguay in the first match and in the second they lost out to Ghana 3-2. Who was on the scoresheet for the Asia side? Not Son, but Cho Gue-sung, a striker on loan at a Korean second-division side, was the one to score twice.

Son is the superstar. You can hear it’s him on the ball before you can see the number thanks to the roar the crowd makes every time he gets involved. But the superstar is getting upstaged.

Is it the injury? Perhaps. You also wonder whether the pressure of being the player who drags his team through tournaments in a Messi or Ronaldo-esque manner is too much for the 30-year-old.

He’s not the only national icon struggling in Qatar. Kane has already been mentioned, but Christian Eriksen, Kevin De Bruyne and Luka Modric can be added to the list.

It’s important to note Son was an architect in the second South Korea goal, with his world-class through ball opening Ghana up, leading to the cross and eventual finish. However, a look at the stats suggests there is more to come from Son. His midfield partner Hwang Inbeom completed the most passes, Kim Jinsu the most crosses and Cho the most shots.

Kane and Son are superheroes when you bring them together, but while apart, it currently seems like their powers diminish.

Son was outshone as his team went down swinging against Ghana. South Korea’s final chance against Portugal beckons and, like dawn, they will hope Son will rise and shine again.

Adam Williams

Swiss try to shut up shop – but must get balance right

Early in the first half, Switzerland full-back Silvan Widmer glanced up at the Brazil penalty box, considered the time and space he had out on the right flank with the ball at his feet… and turned back towards his own half and knocked a safe pass to a team-mate.

It was plain then that, even with Brazil missing Neymar, Switzerland’s gameplan was low risk football in possession. When they didn’t have the ball, they swiftly retreated in numbers, often having all 11 players back to defend.

With 10 minutes to play, the Expected Goals statistic read: Brazil 0.66. Switzerland 0.30. In other words, at the expense of their ambitions, Switzerland had utterly frustrated a Brazil side lacking inspiration without their star No10.

That was of course, until Casemiro blasted in the late winner off an otherwise excellent Manuel Akanji.

When that happens, inevitably questions are asked of the approach. Could Breel Embolo have given Thiago Silva more to think about? Was Alex Sandro’s scrambled block on Fabian Rieder’s cross, when Brazil suddenly looked exposed, an example of the problems Switzerland could have caused if they had been a touch more adventurous?

In his post-match analysis, Sky Sports pundit Gary Neville explained on ITV how Brazil had needed to make subs to get the balance of their team right during the game. Switzerland, who failed to land a single shot on target on Monday, must find the right balance in-game too.

Peter Smith

Super 6 Activates International Mode!

Super 6 is going International! Could you win £100,000 for free? Entries by 7pm Friday.

Sourse: skysports.com