The New Yorker’s theatre critic, Hilton Als, is also an occasional curator of deeply personal art exhibitions, including, last year, a pair of shows devoted to the work of the painter Alice Neel. His latest, “God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin,” at David Zwirner, which opened on Thursday, is a moving tribute to Baldwin and an attempt to give shape to a man who, in Als’s eyes, is celebrated as a writer-prophet of racial injustice but too often overlooked as an artist and a human being. The show features more than sixty works by artists working in various media, arranged throughout four large rooms. Als commissioned original pieces from several renowned contemporary artists, including the South African painter Marlene Dumas, who contributed a series of fourteen portraits depicting Baldwin and the great artists he was connected to—Richard Avedon, Langston Hughes, and Tennessee Williams, among others. Other artists whose works are featured in the exhibition include James Welling, Kara Walker, Diane Arbus, and Beauford Delaney. One remarkable set of Avedon’s images, contained in a contact sheet, depicts Baldwin at home with his family, looking joyful and loose. A rare tape of Baldwin singing the hymn “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” echoes through the galleries. At David Zwirner earlier this week, Als spoke with me about what he hoped to accomplish with this collective portrait. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

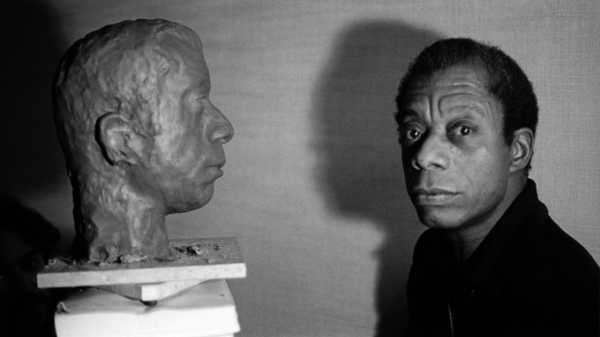

“James Baldwin and his mother, Emma Berdis Baldwin, New York,” December 18, 1962.

Photographs by Richard Avedon, © The Richard Avedon Foundation

You’ve written about your feeling that something was taken away from Baldwin during his lifetime—that, in a way, he was “colonized.” Can you talk a little bit about that?

I think that fame can do terrible things to people. It means that you’re not living in the quiet and solitude that, as a writer, you need in order to develop. I remember William Styron said that there was a weird schizoid element that he saw happening in Baldwin, between the writer who was living for his work and being isolated and then the person who felt that he had to be a spokesperson. I think that Baldwin martyred himself for lots of people, and it meant that his writing became polemical. The less internal life that he was allowed, the more polemical he became.

And so I think, Why not snatch him back from that? If you start listening to him sing, or you see something he said about his mother, or you see them together in Avedon’s photographs, it does something else to your mind, as opposed to “Oh, yes, the civil-rights activist James Baldwin.” It goes back to an idea, which is very important to me, about giving Baldwin back his body, his spirit and his corporeal self. Now we have him singing, and we have him filling space, too.

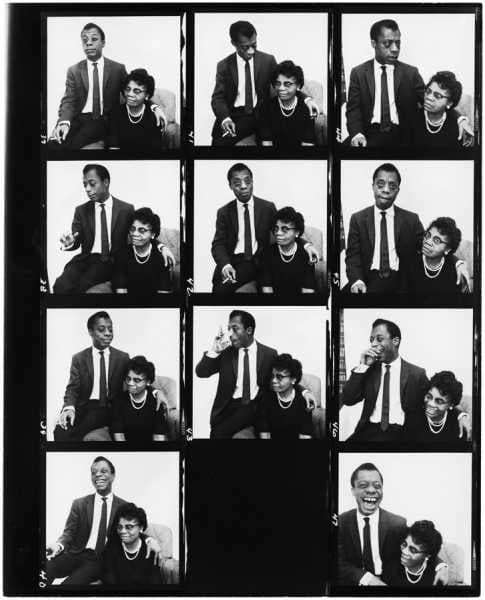

“James Baldwin with the bust of his head by American artist, Lawrence Wolhandler in his hotel room, rue des Grands Augustins, Paris, France,” 1975.

Photograph by Jane Evelyn Atwood / Courtesy David Zwirner

Did you start curating the show with specific artists in mind?

It really began with the photographer James Welling and early photographs he made that were an experiment with color and texture. He was interested in how to make the color black, and thinking about Welling’s work started me thinking about Baldwin’s body and how the body has sort of been taken away from him.

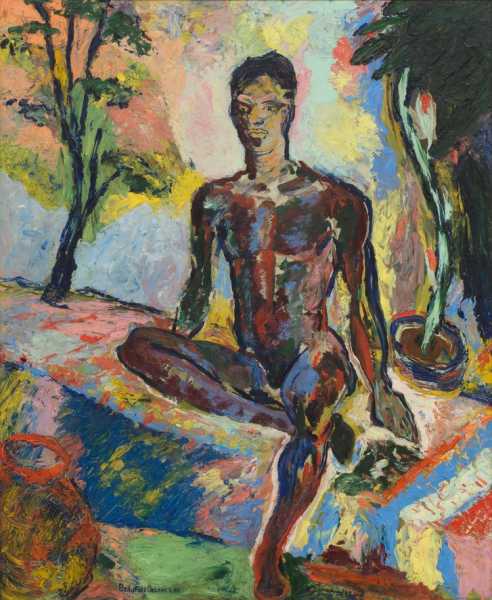

Baldwin wrote beautifully about learning how to “see” from the Harlem Renaissance painter Beauford Delaney, whose work is in the show, and he made a distinction between looking and seeing. I think it relates to the idea of how perception can change you and that, if you’re perceiving something, it means you really put the effort into it. I think Baldwin would be the first to credit Beauford with changing him and helping him to develop as an artist.

“Untitled I (3-27a-81),” 1981.

Artwork by James Welling / Courtesy David Zwirner

Left to his own devices, what more do you think Baldwin could have created as an artist?

He always really wanted to make films and plays. It’s very frustrating to live in a world where you’re not allowed to explore the deeper parts of yourself, not just one part but many other parts. The film industry is, to say the least, such a racially charged and heteronormative space. I think that Baldwin didn’t have a lot going for him in that space except for his fame as a writer, and that’s what he was hired as, not as a director, as he wanted to be.

Still from “An Ecstatic Experience, 2015.“

Artwork by Ja'Tovia Gary / Courtesy David Zwirner

Is that part of why you included a Kara Walker video piece in the show?

Yes, because if you read Baldwin’s piece on Ingmar Bergman, at the end he describes a film he’d like to make, and it’s uncanny how the description mirrors the movie Kara made forty-five years later. His story begins on a slave ship, the Middle Passage; her movie begins on a slave ship, the Middle Passage. He has one intransigent figure; she has one intransigent figure, the Negress, who is a witness to the spoils of profit, sexual and monetary, made on black backs.

Still from “8 Possible Beginnings or: The Creation of African-America, A Moving Picture,” 2005.

Artwork by Kara Walker / Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co. and David Zwirner

Baldwin has been revisited in popular culture today, in movies like “I Am Not Your Negro” and “If Beale Street Could Talk.” Is your show a corrective?

There’s ground that’s been dug up over and over again in order to satisfy the demands of the contemporary world, you know, as an answer to contemporary life. I feel he’s been beaten to death like a dog in that way. I feel badly that the blood has been drained out of Baldwin in order to make a point, let’s say, about a stupid Administration.

I think the contemporary world that has claimed him needs to read him more deeply. People read essential texts and they latch onto the rhetorical, and that’s easy enough to do. You know, Baldwin was a showman, too. But we forget that he was gay, and we forget that he was exiled, and we forget that he was an artist. All of the things that are important to me get marginalized. I think that that’s the real impetus for the show. We need to give him back to himself. If you can deal with him as a person, then inevitably the real politics will come out.

“A young Negro boy, Washington Square Park, N.Y.C.,” 1965.

Photograph by Diane Arbus, © The Estate of Diane Arbus

“Nyado: The Thing Around Her Neck,” 2011.

Artwork by Njideka Akunyili Crosby / Courtesy Victoria Miro and David Zwirner

Can you talk a little bit about how you hoped to portray Baldwin’s sexuality in the show, and what it meant to you to do so?

I think Baldwin was a lovesick person. It’s like Janis Joplin. If you’re making love to twenty-five thousand people and you go home alone, there’s something you’re saying about intimacy, right? That you’re forsaking a kind of intimacy for mass love.

But, also, how do you let anybody in if you’ve had such terrible beginnings in terms of what your blackness means or what you look like? I’m someone who understood that, and it’s taken me a long time not to feel that way. I’m not saying that the scars go away but you can move away from it. And I’m hoping that this show, in a way, helps move Baldwin away from that pain.

That’s why I wanted to end the biographical part of the show with a painting by Delaney, with a kind of brightness: here’s Baldwin’s father, his other father, a gay father. Despite the horror that we face in looking at Baldwin’s life, the hardship, it ends with a kind of hope. Because Baldwin was really kind of saved or sanctified by art more than anything else.

“Beauford Delaney, Dark Rapture (James Baldwin),” 1941.

Artwork by Beauford Delaney / Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery and David Zwirner

Sourse: newyorker.com