If you haven’t read Sarah Kliff and Dylan Scott’s rundown of the various Democratic plans for expanding health care, most of which build on either Medicare or Medicaid, you should. I’ll wait.

The policy questions here are profound, but a lesson of past health care reform efforts is that the policy is shaped by the politics. Three political questions, in particular, will shape both the design and the viability of whatever Democrats come up with. Those three questions are:

1) Will Democrats get rid of the filibuster?

This doesn’t get mentioned much, but it’s perhaps the most important question Democrats will face. The central lesson of both Obamacare and the efforts to repeal it is that getting 60 votes for health care reform is almost impossible.

In Obamacare’s case, the filibuster meant Democrats needed to win every single one of their 60 members, which meant every single Senate Democrat held a veto on the bill. Absent the filibuster, the Affordable Care Act could’ve been substantially more generous, and substantially more ambitious. Sen. Joe Lieberman, for instance, vowed to kill the bill unless both the public option and a proposal to open Medicare to 55-year-olds were axed. If Democrats could’ve passed the bill with 51 votes, they could’ve told Lieberman to take a hike.

“The big challenge that we faced was the filibuster,” Barack Obama said in 2018. “And it’s a weird thing because it’s not something that the average American spends a lot of time thinking about.”

In the GOP repeal effort’s case, it meant that the plans had to run through the narrow budget reconciliation process, a loophole meant to speed budget fixes past the filibuster, but that requires every single provision to directly change spending or taxes. As a result, the GOP’s plans were poorly constructed and often didn’t go nearly as far as Republicans wanted.

President Donald Trump isn’t exactly a master of parliamentary procedure, but he quickly realized that the filibuster was the key obstacle. “The Senate must go to a 51 vote majority instead of current 60 votes,” he tweeted. “Even parts of full Repeal need 60. 8 Dems control Senate. Crazy!”

A bare majority in the Senate will be hard even if Democrats pull a good hand in 2020. But there’s no path to a 60-vote Democratic supermajority. And while it’s possible to imagine a Medicare-for-more bill making it through budget reconciliation, if Democrats want to do something as complex as reconstructing the American health care system, they’re going to need to be able to write legislation in a simple, straightforward way.

That means that Democrats either need to get rid of the filibuster, which they can do with 51 votes, or they need to repeatedly overrule parliamentary challenges to their reconciliation bill, which is pretty much the same thing.

Either strategy will be a tough sell: Senate Democrats have rediscovered their affection for the filibuster in the Trump era; even Minority Leader Chuck Schumer says he regrets weakening the rule in 2013.

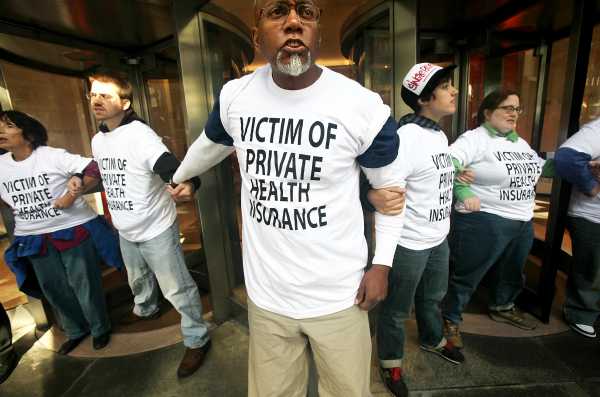

2) Will Democrats replace private insurance with government insurance?

The upside of replacing private insurance with a single-payer system, as both Bernie Sanders’s and the House Progressives’ plans do, is that the system becomes a lot simpler and a lot cheaper, as the government can use its monopsony buying power to force down prices.

The downside is most people like the insurance they have, and being told that their insurance will be canceled and replaced with a government plan could unleash a backlash that annihilates the entire plan.

Remember the fiasco around President Obama’s “if you like your health insurance, you can keep it”? That was more than roughly 3 million plan cancellations, and most of the plans were cut because of how sparse their coverage was. A true single-payer system, one that replaced the existing system, would mean canceling more than 150 million insurance plans, including many high-quality employer-based plans that people love. In that respect, the more ambitious Medicare-for-all proposals go quite a bit further than the current Medicare program, where about a third of enrollees are actually on private insurance.

Vox’s Scott gets at the political dangers here in his piece on the difficulties the employer-based health system poses for reformers:

It’s hard to imagine a Democratic White House convincing vulnerable House and Senate members to reap that whirlwind. But if they don’t do it, it’s harder — though not impossible — to get to both true universality and deep cost savings.

3) Will Democrats pay for their plan?

From the beginning, the Obama administration insisted the Affordable Care Act pay for itself with tax increases and Medicare cuts. This was partly principle — the White House’s concerns about long-term debt ran deep, and Peter Orszag, the budget director, was one of the law’s key architects — and partly politics: Budget neutrality was a condition of support for many of the conservative Democrats the legislation needed to win over in Congress.

That decision limited the bill’s generosity and opened up devastating lines of attack that Republicans used, cynically but effectively, to portray themselves as defenders of Medicare in 2010. A lot of liberals look back on this as Obamacare’s original sin — and after watching Republicans pass tax cuts that, once again, added trillions to the national debt, they feel like suckers for dutifully balancing Obamacare’s books.

The big question Democrats face next time is less how to pay for their health care plans than whether to pay for them. If they decide to fully pay for their plans, then their plans will have to be a lot less generous and there’ll be a lot more losers from the necessary tax hikes and spending cuts.

As of now, the early signs are that Democrats want to hold to their old standards: House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi has said Democrats will abide by the PAYGO rule, which requires both spending cuts and tax increases to be paid for, in the House.

Politics drives policy

I wrote on Friday about how the continued Republican assault on Obamacare has ensured health care remains a central issue for Democrats, and how the nature of the legal assault on Obamacare has pushed Democrats toward Medicare-for-all as an answer.

But there’s a reason that, prior to Obama, president after president failed to pass health care reform. To overhaul something as important to people’s lives as the health care system, you need the trust of the public; the votes in Congress; and, if you’re paying for the plan, a whole lot of money. It’s easy to look back on the places Obamacare fell short and imagine how the law could have been more ambitious or more generous, but the compromises written into the Affordable Care Act were written for a reason: The politics of health care reform are hellish, and the modal outcome is failure.

Right now, Democrats are in the minority, and so their policy proposals can exist in a pure state. But when they get power, the policy choices they actually make will depend on the political framework they choose. As such, while “Would you get rid of the filibuster?” and “Will you keep PAYGO?” may not sound like health policy questions, they very much are. Indeed, they may be the most important health policy questions.

Sourse: vox.com