When the U.S. dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Michael Koerner’s mother, Kimiko, was an eleven-year-old girl living in Sasebo, a mere forty miles away from the epicenter of the detonation. She grew into womanhood on that irradiated land, and married her American sweetheart—a civil servant with the Department of Defense—after a nine-year courtship. They relocated to the U.S. base in Okinawa, where Koerner was born, and then to Arizona. In 1976, at the age of forty-three, Kimiko received a diagnosis: as a likely result of the nuclear radiation, she had a tumor growing on top of her pituitary gland, causing high spikes of adrenaline to pump through her body in moments of distress. That summer, the family returned from vacation to a home that had been robbed. Koerner was thirteen, with his Japanese mother’s slight wrists; his younger brother was six. The two beach-tired boys followed their parents into the house to inspect the damage. Suddenly, they heard screams, and when they entered the kitchen they saw their mother swinging a ten-inch meat cleaver above her petite body, yelling that she was going to kill the neighbor’s kids. When their father tried to calm her down, she picked him up and threw him against the refrigerator.

In his photo series “My DNA,” currently on view at the Catherine Edelman Gallery, in Chicago, Koerner, a professor of chemistry at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, confronts the long legacy of the atomic bomb in his family. Kimiko’s diagnosis was the beginning of a string of medical crises. Koerner’s brother, Richard, died of pneumonia in 2002, at the age of thirty-two. Richard couldn’t fight the infection because he didn’t have a spleen–it was removed years earlier as part of his treatment for Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Around the time of his funeral, Koerner learned, from a cousin, that he had been the eldest not of two boys but of five: three brothers had been lost to crib death, stillbirth, or miscarriage. His mother would die, from complications due to Cushing’s disease, in 2008. “I used to say, ‘Family, what family?’ ” Koerner told me on a recent afternoon. “All of mine are dead.” In “My DNA,” he used collodion tintype, a laborious method of photography that was in vogue during the eighteen-fifties. His process, which involves sloshing, slapping, flinging, and blowing chemicals through a straw, yields abstract works that tackle the subject of atomic radiation through transformation, dilution, and chance—in short, the fraught process of inheritance. “See those fractal patterns, these bursts?” he asked me, pointing at at work titled “Fingerprints #6187.” “They’re mutations.”

“Finger Prints #6175,” 2018.

Richard—who was born on the same day as Koerner, seven years and two minutes apart—received his cancer diagnosis in college. When Koerner accompanied his brother to radiation therapy, the doctors asked Richard to lie down, so that they could lower a topographical lead mask over his chest. The mask was thinnest above the cancerous lymph nodes and thickest above his vital organs; there were marks tattooed on Richard’s chest as guides to help target the radiation. Koerner told me that, as he was asked to vacate the room, for his own safety, he felt the grim irony of the family’s predicament: “They were combatting the results of radiation that causes cancer with radiation that cures cancer.” Before his death, Richard became a chemistry professor, like his older brother. After hearing his story, I looked at Koerner’s work “Richard’s Heart.” I saw the tattoos—rendered as fractal flowers—and the gentle, arrhythmic feathering of the organ, lying on a bed of bronze and blue blossoms: the cosmos of a brother’s care.

“Maru #7286,” 2018.

“Untitled #7433,” 2018.

Kimiko outlived four of her sons. Koerner recalls that his mother sat hunched in the same spot on the living-room couch, stitching temari balls—a type of Japanese embroidery—through each new complication of her disease. He held one of the balls out to me, and we both looked at it closely: thousands of stitches of crimson and marigold, not a single one out of place. If his mother’s art reflects aching precision and control, Koerner’s pieces both embrace these traits and deliberately elude them. “As a scientist, I try to control everything, but I have no control over my genetics,” Koerner said. Currently, his doctors are monitoring a large cyst in his left kidney for signs of malignancy. “I’ve had these issues since I was an embryo,” he said.

“Richard's Heart #4664L-4660R,” 2017.

As a Japanese schoolchild two generations removed from the atomic bombs, I learned their history through the potent efficiency of documentary-style realism, like that of the mannequins in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum—the precisely bent “O” of a child’s mouth, as red, burned skin sags off his bones—or the detail-driven chronicles of Masuji Ibuse’s “Black Rain” and John Hersey’s “Hiroshima.” Such narratives echo in the background of Koerner’s work, but his images offer a more oblique kind of testimonial. There is at once an exacting minuteness and an unnerving vastness to them; in one, we trace multiplying fingerprints clawing into a gray-tinged black; in another, dozens of blue circles blossom into what looks like a CAT scan of a cancerous brain. His photographs ask the questions of those who are too young to have lived through paradigm-altering historical atrocities but not too young to have lived with their consequences: What shall we remember? What has been warped? What and who has, and will, slip from our grasp?

“Three Sisters #860,” 2018.

There’s a plate in “My DNA” that I return to again and again. Titled “Three Sisters,” it shows a trio of veiled figures, their outlines blurred, sandy and bending toward one another, each with a beautiful fractal face. Koerner calls the figures Kimiko, Sumiko, and Emiko: his mother and her two sisters. In 2004, when Kimiko’s condition worsened, Koerner invited the sisters to visit them in Arizona. One couldn’t make it—she was too sick—but Sumiko and her daughter made the trip from Japan. The two sisters hadn’t seen each other in decades. They spoke in Japanese, and Koerner couldn’t understand what they were saying, but he remembers them scrunched on the couch, shaking and laughing together, holding each other’s hands, crying. He thought that their conversation must’ve been like one of his last serious talks with Richard, when he’d asked his brother whether he, Michael, had anything to apologize for. He held those dual memories in his mind when he made “Three Sisters” with elemental silver, “because it can’t be divided,” he said. “It’s not a chemical compound. It is the purest form of silver, and it’s grown by nature.”

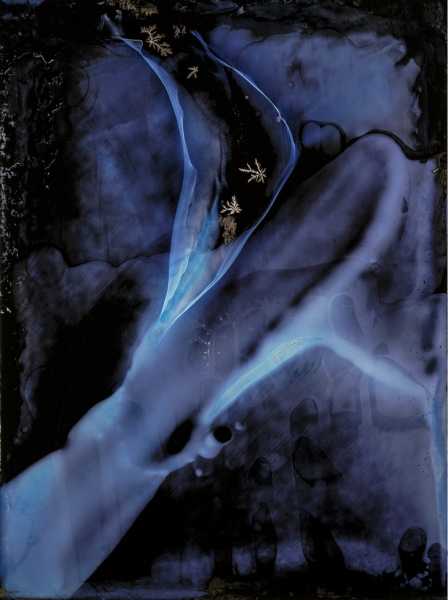

“Waterfalls #7458,” 2018.

“Rōji #7785,” 2018.

“DNA #7262L – #7266R,” 2018.

“Finger Prints #6191,” 2018.

“Coronae #9887,” 2017.

Sourse: newyorker.com