The Earth of the near future will be warmer, with higher seas and stronger storms. And, as we’re learning, it will also have far fewer species of animals.

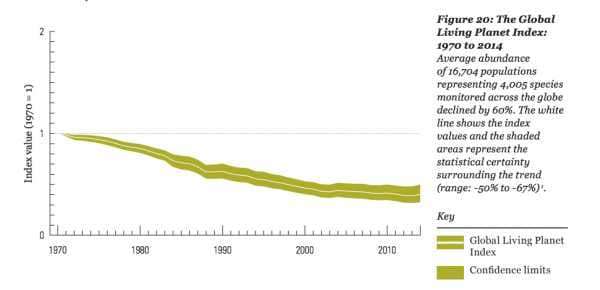

Today, we have new data that paints a bleak picture of what’s happening to the animal kingdom right now. On Tuesday, WWF, the international wildlife conservation nonprofit, released its biennial Living Planet Report, a global assessment of the health of animal populations all over the world. Here’s the topline finding: The average vertebrate (birds, fish, mammals, amphibians) population has declined 60 percent since 1970.

“The astonishing decline in wildlife population … is a grim reminder and perhaps the ultimate indicator of the pressure we exert on the planet,” Marco Lambertini, the director general of the WWF, wrote in the introduction to the report. All these changes have taken place within just two generations.

But to be clear, that eye-popping figure — a 60 percent decline in average populations — is not the same as saying the world has lost 60 percent of its animals.

As science writer Tom Chivers stresses on Twitter, you can have two animal populations, one with 10,000 members and one with 10. If the population of 10 loses five members, that’s a drop of 50 percent. The population of 10,000 would need to lose 5,000 to record the same drop.

The WWF survey is based on data on 16,704 populations of vertebrates, representing 4,000 species. (A population is the portion of a species confined to a particular geographic area. The grizzlies in Yellowstone National Park, for instance, are a different population from the grizzlies up in Canada.)

Regardless, the picture isn’t pretty.

If you zoom in on particular ecosystems, like freshwater streams, lakes, and rivers, you see even more frightening drops. The average freshwater vertebrate species population, like freshwater fish and frogs, has seen an 86 percent drop since 1970.

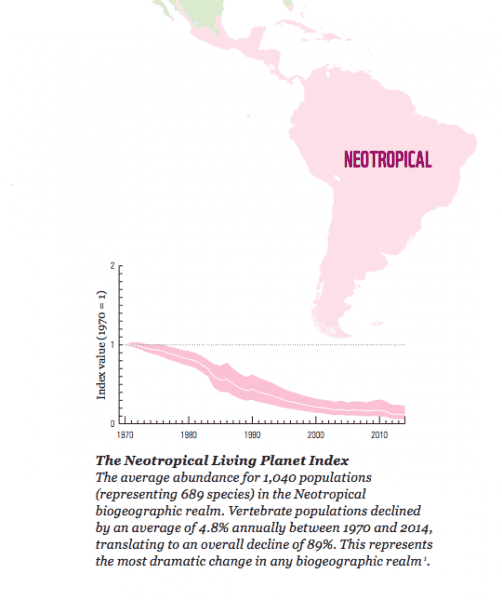

Central and South America — which the WWF report dubs the “neotropics” and which are home to the largest tropical rainforest on the planet — have seen average vertebrate population declines of 89 percent, the most dramatic drop of any regions assessed.

And there’s a bigger global story here that we must reckon with: Humans are a small part of the living world, yet we have a such an outsize impact on it. The WWF report stresses that wildlife faces multiple threats — climate change, habitat loss, pollution, hunting, and invasive species — all which trace back to us and our insatiable consumption patterns.

The WWF suggests the world needs a goal to mobilize behind, like how the Paris climate agreement is an effort to avoid 2 degrees Celsius of global warming. What’s clear is that the status quo isn’t working.

“Despite numerous international scientific studies and policy agreements confirming that the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity is a global priority, worldwide trends in biodiversity continue to decline,” the report states.

Humans are driving a huge array of species to extinction

The world is losing biodiversity, and fast. If you take stock of all the studies that point to the fact that we’re living in an age of mass extinction, perhaps even the sixth mass extinction, it can all feel overwhelming.

It’s not just the vertebrates.

As a recent study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences outlines, between 1976 and 2013, the number of invertebrates (like insects, spiders, and centipedes) in Puerto Rico’s rainforest caught in survey nets plummeted by a factor of four to eight. When measured by the number caught in sticky traps, invertebrates declined by a factor of 60.

A 2017 study in Germany noted a 75 percent decline in flying insects over three decades. “The widespread insect biomass decline is alarming,” the authors wrote, “ever more so as all traps were placed in protected areas that are meant to preserve ecosystem functions and biodiversity.”

Mammals, the branch of the animal kingdom to which we belong, are also in peril, as another study, also published in PNAS in October, illustrates. More than 300 mammal species have been wiped out since humans overran the world after the last ice age (and an additional 25 percent of all mammals alive today are threatened with extinction). The study asks a simple question: How many years would it take for evolution to naturally replace all the species that have died as a result of humans?

Their answer: 3 million to 7 million years. Science writer Ed Yong points out “that’s at least 10 times as long as we have even existed as a species.”

The past few decades have seen a massive die-off of amphibians, which scientists fear are some of the animals most vulnerable to losses in a rapidly changing world. That may be because amphibians need healthy aquatic and terrestrial environments to thrive. Change just one enough and species suffer.

In 2010, a survey of 25,780 species of vertebrates found that 41 percent of the amphibians were threatened with extinction. “On a per-species basis, amphibians are in an especially dire situation, suffering the double jeopardy of exceptionally high levels of threat coupled with low levels of conservation effort,” the study noted. Since just 1970, 200 species of frog have perished.

What we lose when we lose species

It’s important to take stock of what we lose when we lose species. A 2017 report in Science Advances found that around 60 percent of primate species are threatened with extinction — all due to human activity.

The report found every member of the primate family Hominidae (great apes, which includes gorillas and chimpanzees) is endangered or critically threatened (except for us). Around 87 percent of Indriidae (larger lemurs) are similarly endangered or threatened.

Think of what that means: Primates are our closest relatives on Earth. If we can understand them better, we can understand ourselves. Here’s how Carl Zimmer at the New York Times explains it:

But don’t necessarily consider primate losses to be more important, or painful, than insect losses. Insects and other arthropods form a hugely important foundation in many ecosystems’ animal food webs. They also are the world’s pollinators, ensuring that plants produce new seeds and new generations. Without the foundation of insects, the ecosystem collapses.

We need to take stock of the wildlife we’ve lost

Earlier this year, researchers tried to estimate a weight for all of life on Earth. It was a fun exercise, putting humanity’s relative small weight on Earth in dramatic contrast to the weight of all the other forms of life. There’s an estimated 550 gigatons’ worth of carbon of life in the world. And all humans weigh just 0.06 gigatons.

If every person on the planet were to step on one side of a giant balance scale and all the bacteria on Earth were placed on the other side, we’d shoot violently upward. That’s because all the bacteria on Earth combined are about 1,166 times more massive than all the humans.

The authors of the weight estimate were also sure to calculate what was missing from their figures. They estimated that the mass of wild land mammals is seven times lower than it was before humans arrived. Similarly, marine mammals, including whales, are a fifth of the weight they used to be because we’ve hunted so many to near-extinction.

Although plants are still the dominant form of life on Earth, the scientists suspect there used to be approximately twice as many of them — before humanity started clearing forests to make way for agriculture and civilization. Animals are going extinct 1,000 to 10,000 times faster than you’d expect if no humans lived on Earth.

With so much devastating and widespread loss, it’s hard to say where we should focus our attention — other than just working to stem the progression of climate change. In Science, Jonathan Baillie, the chief scientist at the National Geographic Society, and Ya-Ping Zhang, the vice president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, argued that half of all land should be protected for wildlife by 2050, to give plants and animals a chance to thrive.

This is a lofty goal. But we’ve taken so much from wildlife. We need to think more about how to stop taking environments away from plants and animals. “Simply put,” they write in Science, “there is finite space and energy on the planet, and we must decide how much of it we’re willing to share.”

Sourse: vox.com